When South Africa Was Home to the ‘Firewalkers’ of Karoo

The reptilian critters may not have survived, but they made sure to sign off feet first.

South Africa has pretty much always had megafauna. Today, the country is peppered with safari parks and game reserves for the large carnivores, ungulates, and other creatures that abound throughout the African continent.

But nearly 200 million years ago, at the onset of the Jurassic Period—the age that saw the rise of such popular creatures as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops—it was a fiery hellscape, plagued by regular volcanic eruptions that pushed life in the area to its limits.

Yet life did persevere, as evidenced by the recent discovery of dinosaur footprints on South Africa’s famous Karoo Basin, which boasts a trove of fossils dating back to when the area was part of the supercontinent Gondwana.

“The tracks are preserved in sandstone, sandwiched between basalt layers,” says Emese Bordy, a sedimentologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and lead author of the new study, published today in the journal PLOS One. “The properties of the sandstone allow us to tell that the tracks were deposited in seasonal streams that ran during flash-flood events.”

Bordered by ocean on three sides and located at the nadir of the continent, South Africa today is tropical and lush. But even now, some of it is semi-arid—and in certain places, entirely devoid of water. The term Karoo, after all, comes from a Khoisan word for “land of thirst,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

That term couldn’t be truer for the area in ancient times. A hundred million years before the ascendance of T. rex, large volcanoes here vomited lava across the region, burning up the surrounding land and smoking out organisms in search of new habitats.

On a South African farm—located through a combination of academic detective work and citizen science—Bordy’s team found 25 footprints from a slew of ancient animals. One of them was a new ornithischian—a dinosaur group whose members boasted birdlike hips, like Stegosaurus—in addition to carnivorous two-footed dinosaurs and some of their four-footed herbivorous prey. Other footprints belonged to early synapsids, the mammal-like animals that would eventually evolve into, well, us.

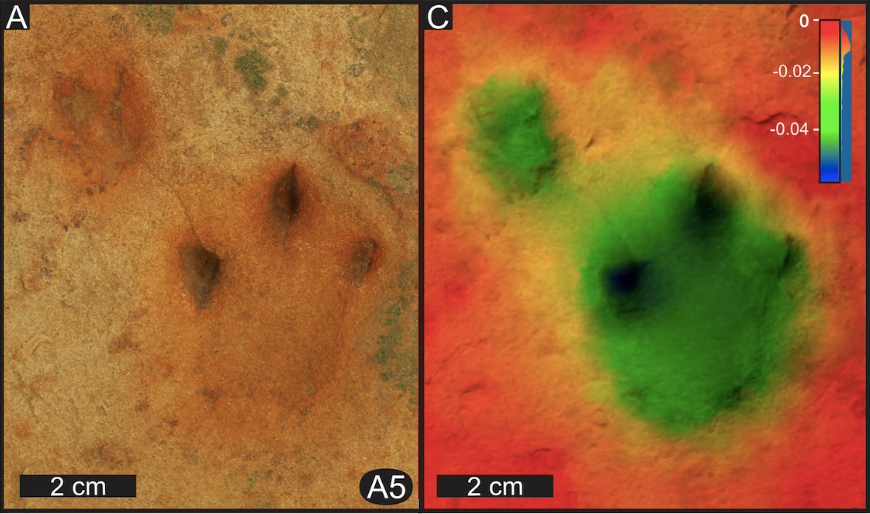

The team catalogued the footprints in three dimensions using photogrammetry, which helped researchers extrapolate the approximate weight, size, and speed of the Early Jurassic dinosaurs. They determined that the creatures likely trotted and scrambled across the streambed during a brief respite from the violent eruptions that seized the area—a respite that conveniently preserved the footprints between two massive layers of cooled lava, which today form large basalt deposits that blanket the South African landscape.

“All in all, one would imagine that it was not very nice there all the time,” says Bordy. “But clearly it was habitable between the eruptions.”

Trace fossil beds like these, called ichnosites, aren’t common in South Africa, though the entire country is filled with fossils. Despite the bone troves, though, it’s hard to say what made the volcanic region of Karoo a literal hotbed for life.

“One possibility is that at least between 265 and 180 million years ago—that is, for over 85 million years—this part of southern Africa was a fairly stable continental interior,” says Bordy. Clearly it was home to a vast array of terrestrial animals and plants that thrived under varying conditions. But, says Bordy, “questions like ‘why so many fossils are here’ and ‘why these organisms found the Karoo a hip place to live in’ are not easy to answer.”

As hip as it was, neighborhoods change. After the frenzy of volcanic activity, Gondwana broke up, and the tranche of earth containing the Karoo Basin drifted for millions of years. The life on it changed all the while—evolving, dying out, evolving again, and eventually forming the South Africa we know today. But some of the ancient world’s residents refused to leave without first leaving their mark.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook