Why a Museum Owns a Chocolate Company’s Embroidery Collection

The Whitman Sampler Collection is pretty sweet.

While most Valentine’s Day chocolate comes in a red- and white-trimmed heart, your sweetheart may have recently handed you a golden box: a Whitman’s Sampler. With its packaging reminiscent of old-fashioned cross-stitch, Whitman’s Samplers seem demonstrably vintage, evoking another era.

But when the already venerable Whitman’s candy company unveiled the Sampler in 1912, the patterns on its box were meant to remind customers of an even earlier, homier era. As legend has it, Whitman’s president Walter Sharp used a piece of embroidery, or “sampler,” made by his great-aunt as inspiration for his new line of fancy boxed chocolates. Consumers seemed to enjoy the vintage look and crafty appeal of the packaging (one billion Whitman’s Samplers have been sold since 1912) as well as the implicit invitation to “sample” the different chocolates from Whitman’s most popular boxes.

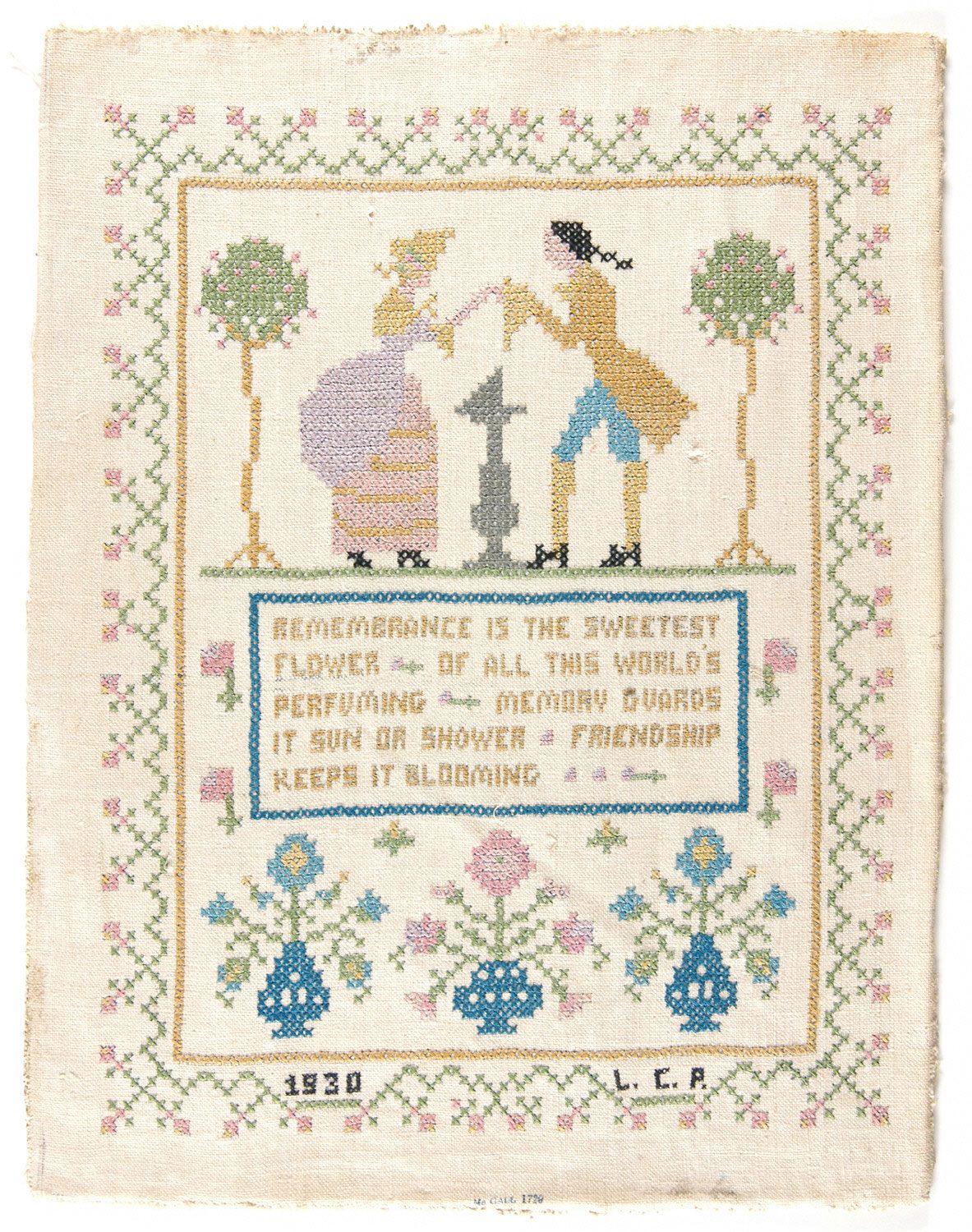

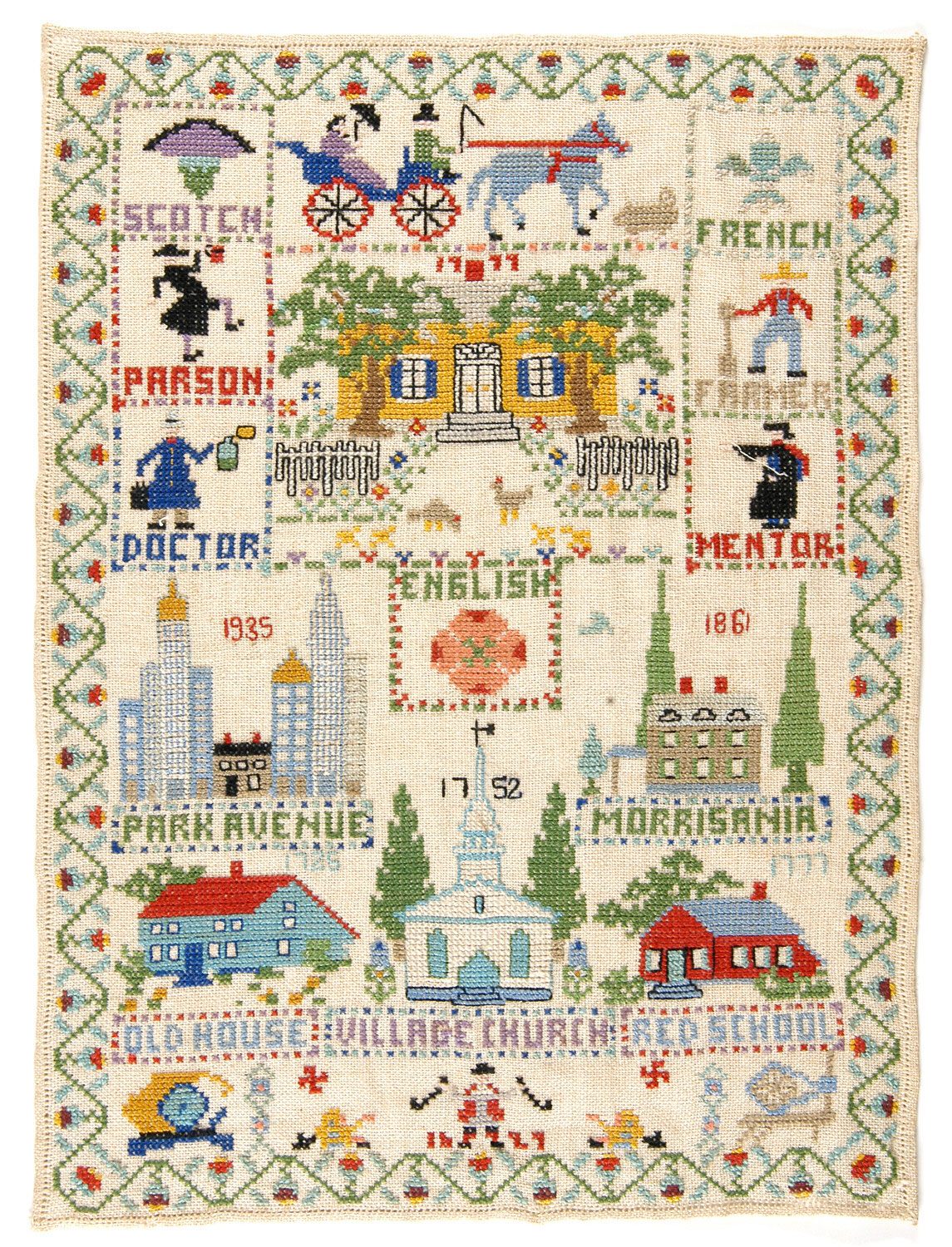

As the popularity of the Sampler grew, Whitman’s collected actual samplers. Between 1926 and 1964, the Philadelphia-based company sought embroidery from local dealers. With examples spanning from the 17th to 20th centuries, the company even put the vintage samplers on display to draw customers to their stores and showrooms. Geographically, the samplers in the collection were diverse: Along with a significant number of early American samplers, the collection included Russian, Spanish, Mexican, and Dutch work.

The term for such panels of embroidery comes from the French term essamplaire, since they were meant as a way for girls and women to practice, showcase, and record their embroidery skills. Samplers were often embroidered with letters, numbers, or even bucolic scenes, and families kept them as decor and heirlooms.

While sewing and embroidery were long considered essential life skills, samplers that have survived to today are now considered folk art. Notably, many young women stitched their name and age onto their work, giving them a lasting voice that otherwise may have been denied them. While women often stitched them as memory aids for different stitches, or even to demonstrate their suitability as a wife and homemaker, samplers also reveal creativity and craftsmanship.

That’s why Pet, Inc, the company that owned Whitman’s, donated the collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969. The eclectic mix includes renderings in thread of everything from the Liberty Bell to towering skyscrapers to perky-tailed dogs. In 1833, Janet Tomson Ash, an English 10-year-old, made a sampler with stunning expertise, stitching out a neat house in a design reminiscent of modern pixel art. Sometimes, the skills seem in progress: One sampler declares, “Kind Friend, behold for it is Truth, This is the Practice of My Youth.” One sampler, made by an 11-year-old in 1829, contrasts flowers with a kneeling, chained man: a common anti-slavery motif.

By the time of the donation, making samplers was more of a hobby than a necessity for women. (Though, recently, they’ve had a feminist revival.) Yet the museum continues, on occasion, to display selections from the Whitman Sampler Collection: a sweet reminder of countless women’s craftsmanship.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook