The 12,000-Mile Road Trip That Captured the Sounds of the World

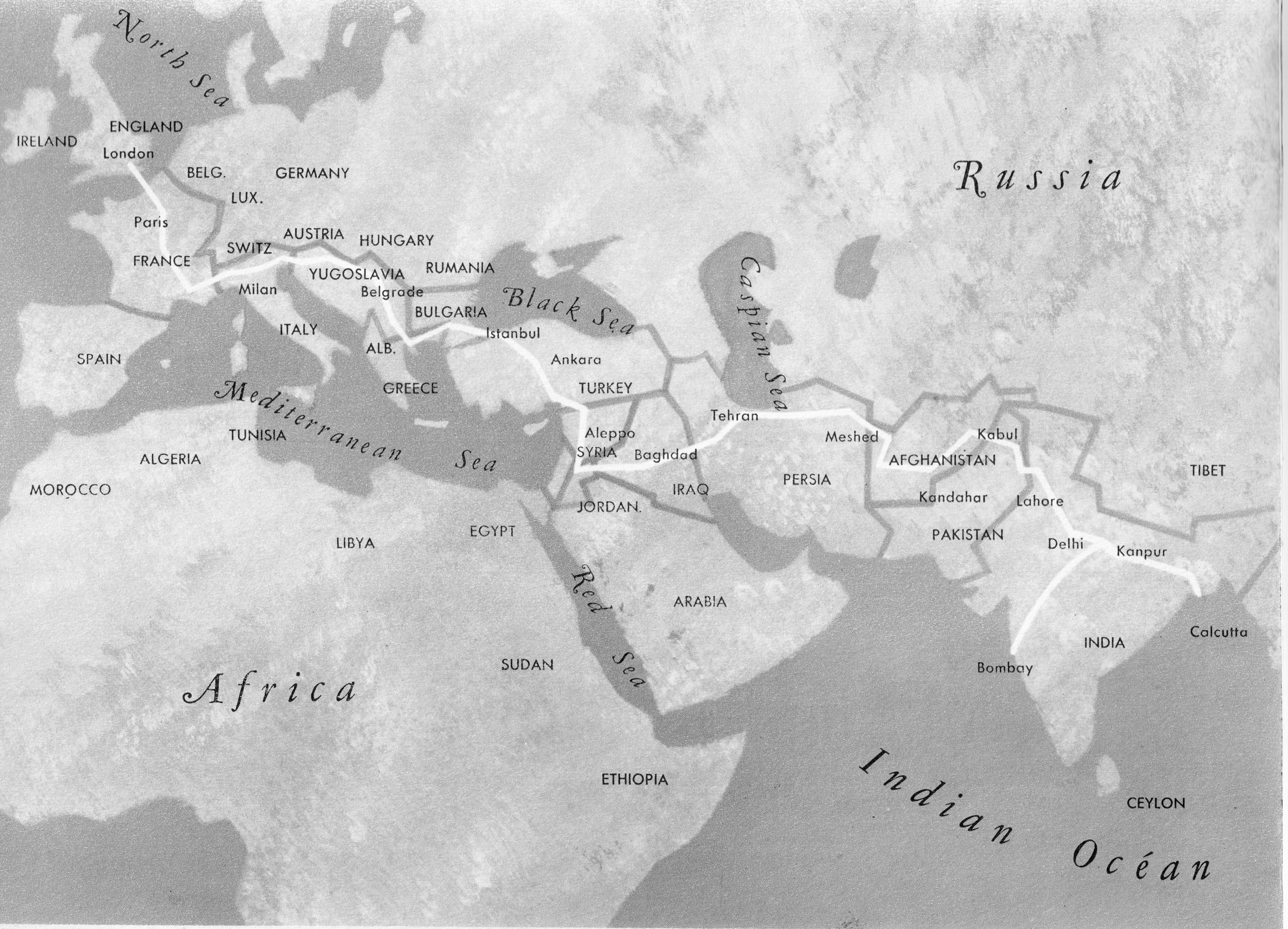

In 1955, Deben Bhattacharya traveled from London to Calcutta in a milk van and recorded over 40 hours of music.

It was a cool summer evening in 1955, and three men—a Bengali, a Frenchman, and an Englishman—sat by an Italian roadside enjoying a picnic of bread, cheese, and olives. The garnet-colored Chianti wine helped ease the tension they’d felt while preparing for the trip. It had taken them weeks of planning, but they were finally on the road and heading east.

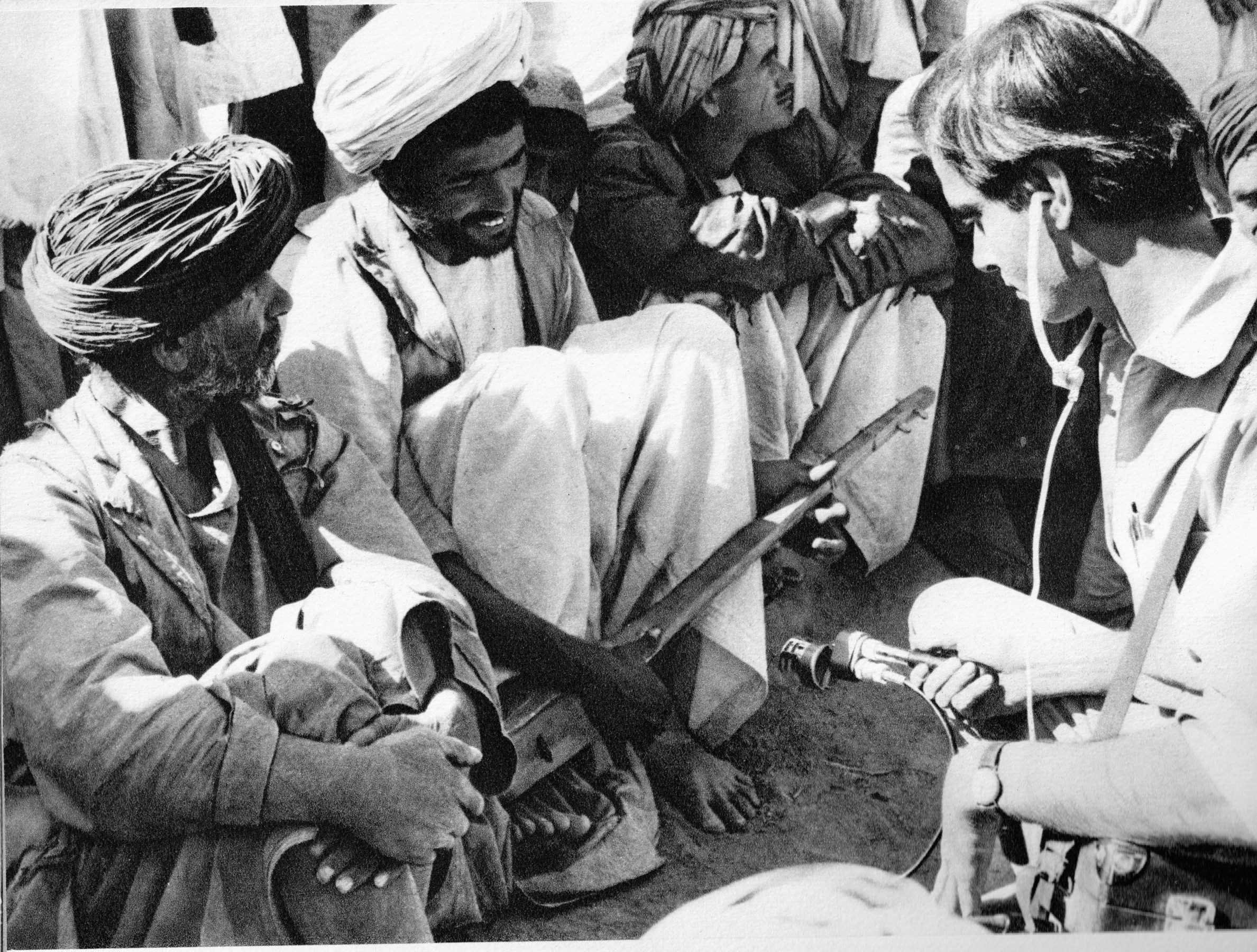

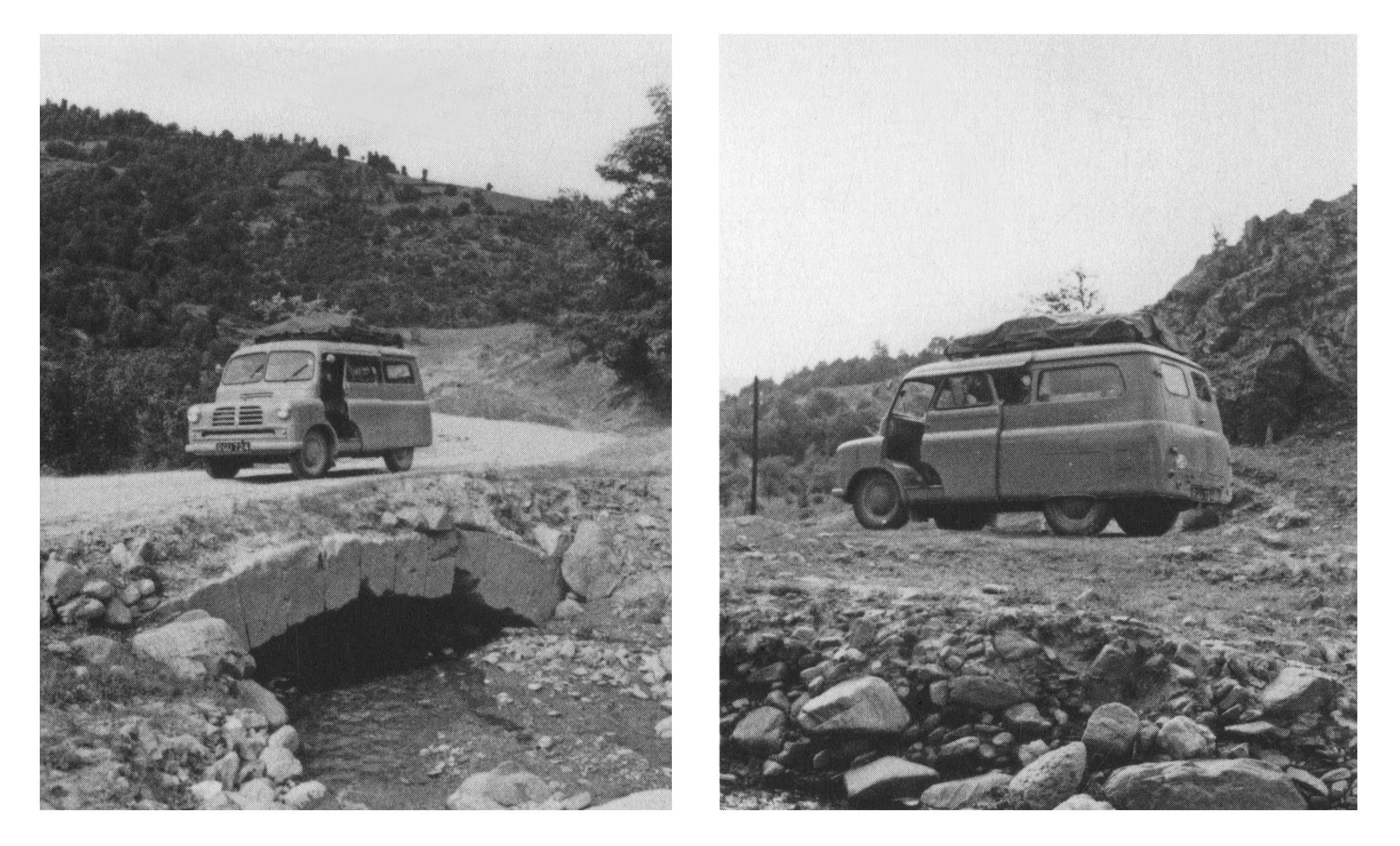

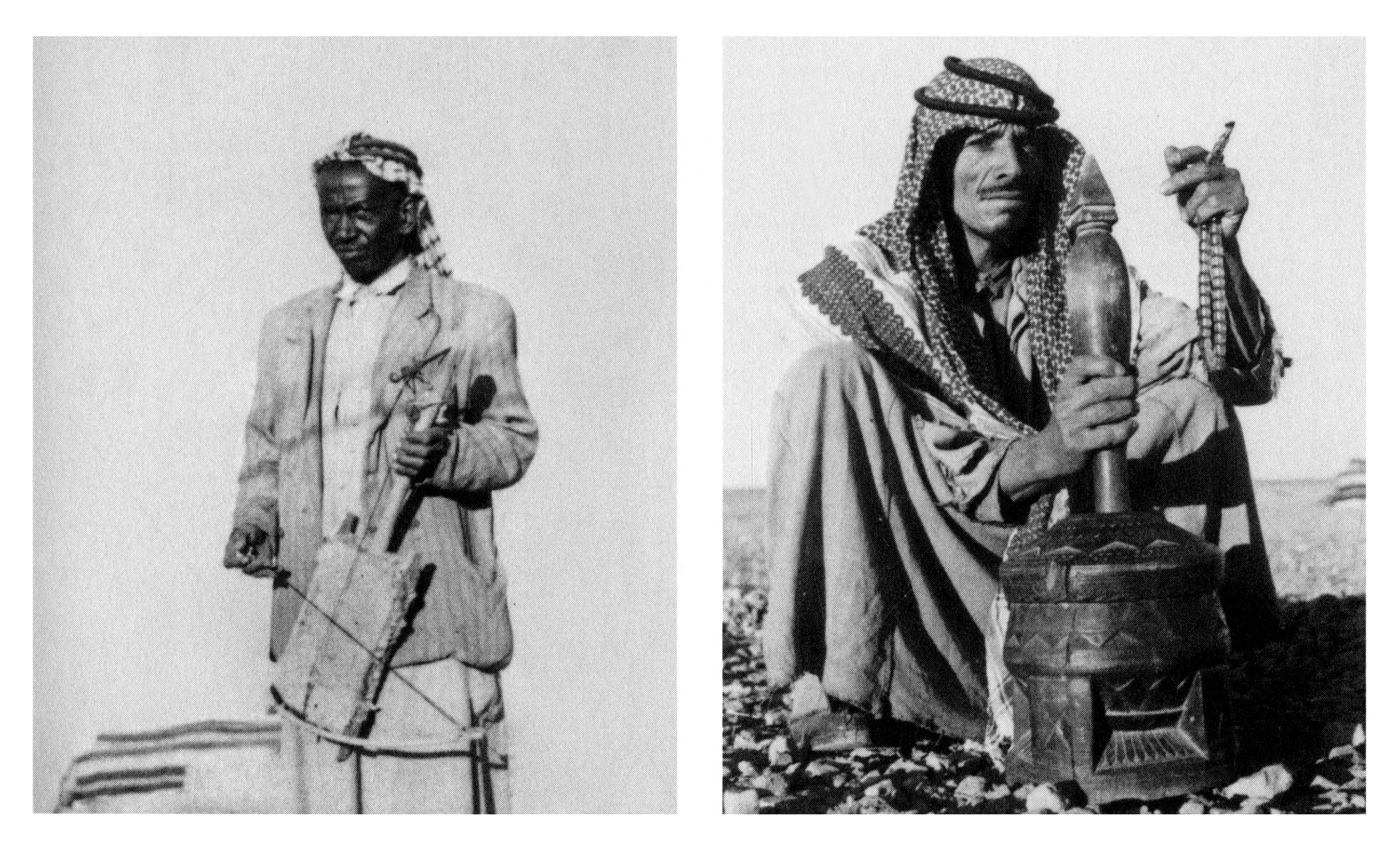

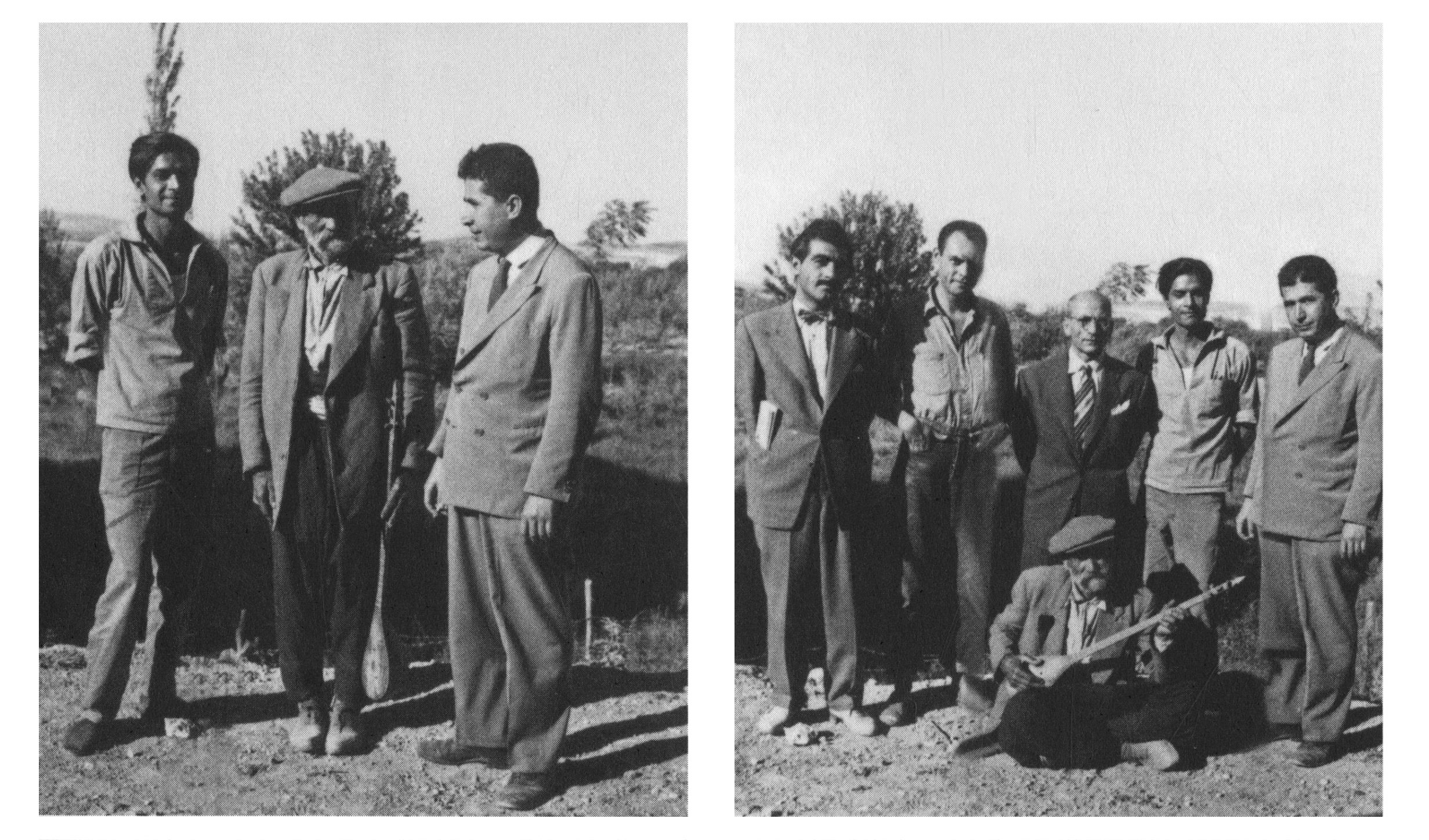

Over the next six months, they would travel in a battered milk van all the way from London to Calcutta, passing through Greece, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and finally, India. They hauled heavy tape recorders and cameras with them across the desert, where they stayed with Bedouins and recorded their chanting. In Syria, they witnessed an illegal dervish performance, and in Afghanistan they listened as a new acquaintance sang for them of love and loneliness.

At times they would be met by ambassadors and dignitaries. More often, they relied on the hospitality of complete strangers.

The unprecedented expedition was spearheaded by Deben Bhattacharya, a Bengali poet, filmmaker, and amateur ethnomusicologist.

Bhattacharya was born in Benares—also known as Varanasi, the world’s oldest living city—into a family of scholars and Hindu priests. His father practiced Ayurvedic medicine, and the family ran a traditional Sanskrit school. As a child Bhattacharya helped out by performing religious rituals: His head was shaved except for one small tuft of hair, and he was known by everyone as “the little priest.”

In 1949, Bhattacharya left his family and his life in Varanasi and traveled to the U.K. to explore a wider world. “He soon immersed himself in music, and that was to become his source of livelihood,” wrote Jharna Bose-Bhattacharya, his widow, in a new book featuring her husband’s notes.

In London he began working as a radio producer at the BBC and had access to a vast archive of music from all over the world. But he felt that these recordings were stiff and impersonal. The music was far too detached from its context, and there was little trace of the people who had created it, he thought. It lacked a human element.

Bhattacharya decided to travel through the Middle East and capture the music and sounds of its people himself.

There was only one problem, though: He couldn’t drive.

With 12,000 miles ahead of him, he enlisted the help of a young English architecture student by the name of Colin Glennie. Glennie didn’t have much interest in “music from the Eastern World,” he would write in a letter to a journalist decades later, but he did love buildings. He accepted the offer to drive the converted milk van on the condition that they visit Chandigarh, the Indian city designed by the modernist architect Le Corbusier. Bhattacharya agreed. For a short time they were also accompanied by Henri Anneville, a French journalist with a thirst for adventure.

During the journey Bhattacharya recorded over 40 hours of music, some of which would be released on the 1956 LP Music on the Desert Road: A Sound Travelogue. He went on to become one of the most renowned ethnomusicologists to ever have lived, and he changed the way people listened to music from around the world. Frank Zappa once cited Music on the Desert Road as one of his biggest influences.

The 1955 journey was a crucial moment for Bhattacharya. He perfected his trade, learning how to record and how to use a camera, all the while getting to know the cultures and traditions whose music he loved. Throughout the trip, he kept a travel diary and wrote about the people he met, the music he heard, and the small acts of kindness that kept his spirits high during the journey.

When he returned to Europe, Bhattacharya typed up his notes, collected all his photos and musical annotations, and wrote an introduction to what he hoped would become a book. Somehow, though, he never got around to publishing it. Maybe he was too busy planning his next adventure, or maybe he thought the recordings told the story well enough on their own. In any case, the manuscript was put away and almost forgotten about for 60 years. When Bhattacharya died in 2001, it seemed unlikely that it would ever be published.

But Jharna, his widow, never gave up on the diary. She knew it was an important piece of work. Although her husband published several literary works, none were quite as personal as his 1955 diary. “It just shows exactly what he was like, so at ease and good with people,” she says.

Like many people with a love of folk and popular music from around the world, Robert Millis, who works with Seattle-based record label Sublime Frequencies, regarded Bhattacharya as a pioneer. Many of the records which ignited his love of Indian, African, and Middle Eastern music contained recordings made by Bhattacharya during his many trips. “He influenced me a lot, but it was a secret influence at first,” says Millis, “because I didn’t know that he had actually put together many of the records I was listening to.”

In 2013 Millis was in Calcutta promoting his book about India’s legendary 78rpm Gramophone industry when he heard that Bhattacharya’s widow lived close by. He jumped at the chance to meet her. The couple’s apartment was just what he’d imagined: Pieces of art, hundreds of books, old photographs, and an eclectic assortment of instruments filled the space. He was amazed when Jharna showed him a wad of onion skin paper filled with Bhattacharya’s neatly typed notes.

“I knew about Music on the Desert Road but I didn’t know he had written anything,” Millis says. “Then Jharna pulled out the manuscript and said it was her dream to always have this published.”

Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, released on Sublime Recordings on November 2, 2018, brings together Bhattacharya’s original diary, introductions from Millis and Jharna, and all the original recordings from the expedition. You can listen to the beats of Bedouins grinding their coffee in the desert, or to the recitation of an epic poem from Iran; there are hauntingly beautiful love songs from Afghanistan, and devotional songs from India.

“The music on this record represents selected pieces from a collection of over 40 hours of recording made during an overland journey to India. The journey started from London in the middle of August, 1955, and ended in Paris by the following March,” Bhattacharya wrote in his introduction.

“If reasons of ethnology influenced my choice, they did so only incidentally; my own enjoyment was the main criterion.”

And this is perhaps the most striking aspect of this book: Although the purpose of the journey was specifically to record music (he had been sponsored by Argo Records, and been given a sum of money by EMI), for Bhattacharya it seemed to be as much about making connections. His diary is replete with warm, attentive descriptions of the people he met and the small moments they shared.

Some parts of the journey were difficult. Early on, Bhattacharya and Glennie passed through Istanbul, where violent mobs had recently attacked the city’s Greek minority. The atmosphere was tense and unfriendly, and it reminded Bhattacharya of riots he had experienced in India. He was feeling despondent: “I disliked Istanbul as I disliked myself for being so badly affected by it. I forgot that no nation in the world is free from fanaticism.”

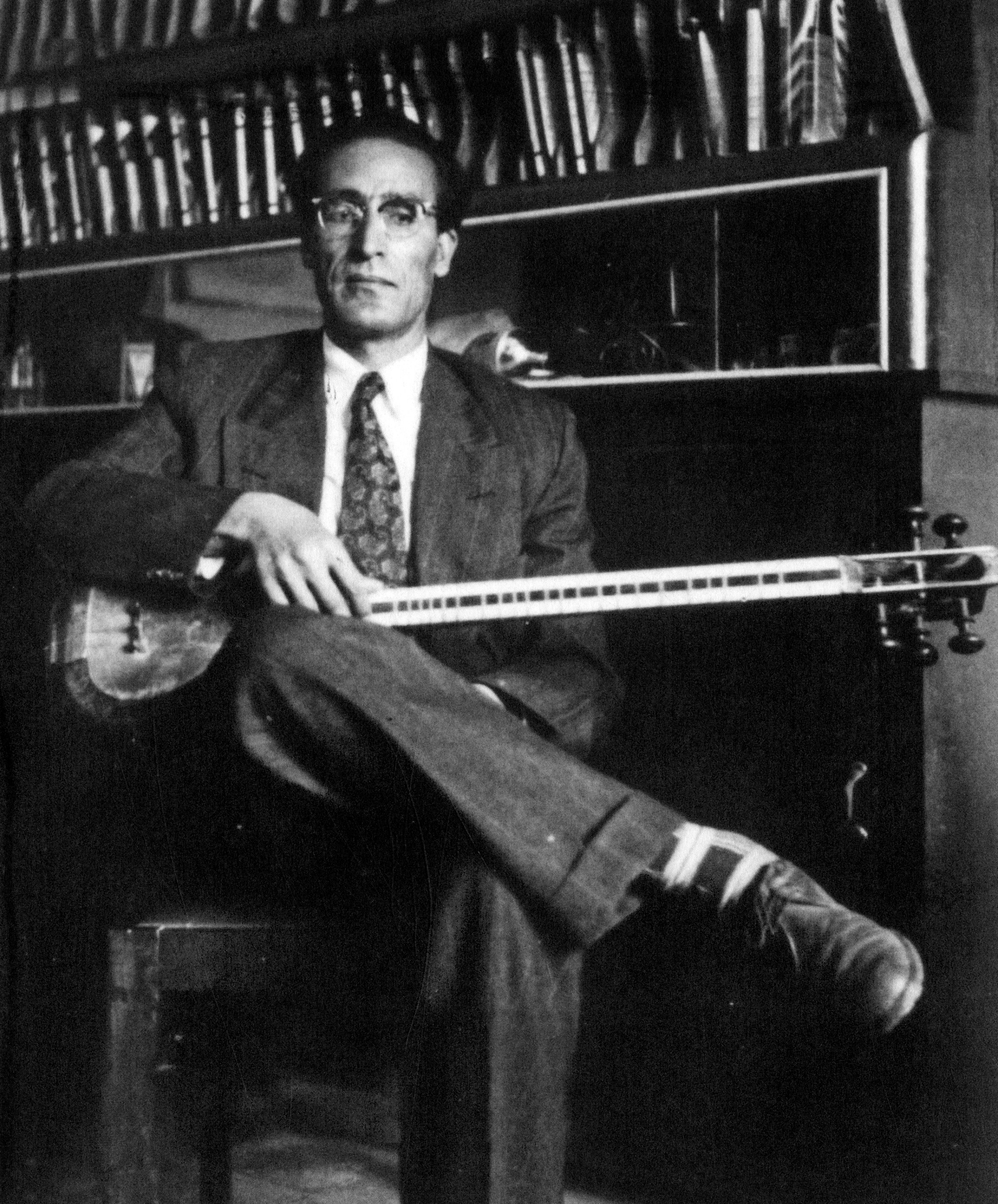

The feeling of uneasiness stayed with him all the way to Ankara. But then, Bhattacharya spotted a man carrying a cümbüş, a stringed guitar-like instrument from Turkey. When asked, the man began playing and singing melancholy love songs from Central Anatolia. Bhattacharya described his shabby clothes, his shy smile, and sad eyes. He felt an instant liking for this lonely man.

“Turkey was beginning to get human and interesting,” he wrote. “As soon as I had established this one temporary human contact, I felt more myself again, a modest wanderer in search of music and personal relationships.”

There were to be many more such meetings on the way to Calcutta, and some of the people he met during the journey became lifelong friends.

Bhattacharya “wasn’t always trying to highlight the best performance,” says Millis. “It was more the emotion in the music and his interaction with the musician that mattered. Deben’s work always seemed to have a nice touch of the music fan about them, and somehow it comes out in the way he records.”

Some of the countries through which he traveled—Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan—have become engulfed in a seemingly never-ending cycle of conflict and violence. “The desert today is a scene of bomb craters, people maimed or dead while refugees stream out in a state of misery, chased from country to country, their laughter and music buried in the sands, literally and metaphorically,” writes Jharna in the new book’s introduction. “What would Deben make of today’s world?”

Narratives of destruction and violence appear to dominate public discussion of Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. But of course, there is so much more to them than that. Through his thoughtful musings, his deep appreciation for those who agreed to play for him, and his gratitude to those who helped in any small way, Bhattacharya shows us a different side to these consistently misrepresented countries.

And his recordings play a small, yet incredibly important, part in reconstructing their rich and ancient cultural history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook