The Donkey Refuge Where Burros Become Coyote-Kicking Livestock Guardians

With the right training, feral donkeys go from zero to hero.

A NASA facility in California has been dealing with odd interference. The Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, one of three worldwide facilities of the Deep Space Network that tracks and communicates with far-off spacecrafts, lies in the dry, often scorching heart of the Mojave Desert. But when it gets particularly hot, something strange happens. The office foyer fills with donkeys, preventing scientists from entering or leaving the building.

Despite several large removal efforts, “wild” donkeys, or burros, are abundant in the Mojave Desert. Seeking shade, they crowd beneath trees, buildings, and, on occasion, incredibly important NASA satellites. But donkey interference, as silly as it sounds, extends far beyond the day-to-day disruption of space scientists. According to Mark Meyers, executive director of Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue (PVDR), there are too many donkeys in America, and we simply don’t know what to do with them.

“Places like Death Valley, the Mojave National Preserve, Fort Irwin, and the Naval Air Weapons Station [China Lake] all have giant donkey populations,” says Meyers. “There’s just no burro money to manage them.”

That’s where Meyers comes in. Peaceful Valley, the largest rescue organization of its kind, has recently been tasked with removing thousands of donkeys from national parks across the country. Meyers spends his days venturing into these donkey hot zones, catching them using humane water traps (an enclosed space with water, food, and no exit), and bringing them to his Texas headquarters. But what does one do with tens of thousands of formerly feral donkeys? Historically, not too much. But Meyers and his team are working to change that. At PVDR, donkeys are sorted, taken to donkey school, and given a new life, often as companion donkeys or pets. But burros with a wild side, it turns out, are huge boons for ranchers across the U.S. seeking effective, humane ways to protect their herds. With the help of PVDR, unwanted “wild” donkeys are becoming guardians, set out to pasture with goats, sheep, and even cattle, to keep them safe from predators.

The plight of the American donkey is a strange one—the animal has been simultaneously federally protected and completely overlooked. But the U.S. didn’t always have a donkey problem. In fact, for a long time, it didn’t have donkeys at all. Brought into the country by the Spanish and Portuguese, donkeys and mules were used on farms for a variety of agricultural work, and as pack animals on the Oregon Trail. During the Gold Rush, they toted water, ore, and supplies to camps—and were often taken into mines. But with the development of industrial and agricultural technology, and the end of the Gold Rush, owners left their animals behind.

That wasn’t the end of the rope for the American donkey, though. With few natural predators and an impressive reproduction rate, herds of burros can double in four to five years. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, the Department of the Interior began taking issue with the “veritable pests,” who destroyed trails and forced out the antelope, in the 1920s. Over the next few decades, thousands of burros were rounded up and shot in Death Valley and the Grand Canyon.

At the same time, wild horses (which tend to garner a bit more public sympathy) were caught up in a similar situation. But “mustanging,” or shooting wild mustangs, angered activists and those who viewed them as equine embodiments of the “Spirit of the West.” Congress, agreeing to preserve these eminent equine relics of the Wild West, grouped the two species together, unanimously passing the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, which effectively protected wild horses and burros on any land belonging to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Services.

Since then, the government has struggled to control populations in national parks, reservations, and natural preserves. The government spent over one million dollars in the 1980s capturing and retaining around 6,000 burros from Death Valley National Monument. Meyers witnessed the change firsthand. “We went from seeing donkeys all the time to seeing none,” he says. But after federal funding ran out, the donkey population once again skyrocketed. Meyers estimates there are nearly 3,000 donkeys in Death Valley National Park today.

And no matter how adorable they may be, donkey takeovers pose a big problem. Technically an invasive species, the donkey can quickly wreak havoc on ecosystems. When water and food are scarce, donkeys outcompete native species with similar diets such as bighorn sheep and desert tortoises. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, Death Valley burros “ate a disproportionate amount of native perennial grasses,” claiming “grasses were up to 10 times more abundant in areas protected from burros.”

However, Meyers notes that the impact of burros on desert ecosystems isn’t always negative. Springs in Death Valley are often surrounded by dense vegetation, thick reeds, and trees that can obscure the path to the water. According to Meyers, burros will barrel into that vegetation, creating access to that water. “Donkeys will also dig a hole four feet deep just to find water, making it available for other animals as well,” he notes. “So if you remove the burros, you’re removing access to water for deer, bighorns, and everything else.”

But when donkeys in search of water have to get creative, they can cause big problems in the human world. Thirsty donkeys venture into towns, crossing busy streets and even causing car accidents. At Fort Irwin, a major military training base in the Mojave Desert, donkeys congregate beneath the only source of shade they can find, large targets set up throughout the base. When the soldiers in training hit their targets, Meyers says, they blow up the creatures standing beneath them, too.

The government has attempted to use various tactics, from sterilization to, as a last resort, shooting them. More recently, burros have been rounded up en masse by helicopter and placed in government holdings. But there are simply too many of them, and they don’t get adopted fast enough. Meyers says there are currently around 43,000 horses and donkeys in holding, which costs the government (and taxpayers) somewhere around $49 million per year. Once a donkey turns 10, though, it’s considered unadoptable and can be sold—which, technically, makes it available for slaughter.

Meyers’s love affair with donkeys began when his wife bought a donkey as a companion for her horse. “It was just like a big dog,” he says. He noticed other donkeys in the area, too, that were without homes, often victims of abuse or neglect. “She’d buy them, and I’d spend all my evenings just talking to donkeys, fixing whatever ailed them.” Once the couple had acquired a small herd of 25 donkeys, they decided it was time to turn this backyard hobby into something bigger.

Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue, Meyers’s brainchild, is the largest rescue of its kind. Recently, it’s been tasked with removing thousands of donkeys from various national parks, which have a zero burro tolerance policy. “Because we’re so big, we’re able to do this. Nobody else can sign on the dotted line and say, ‘However many burros you have, we’ll take them.’”

But his organization isn’t just focused on safely removing donkeys. It’s also about humanely repurposing them. Burros that enter Peaceful Valley are given a microchip for tracking, proper vaccinations and hoof care, and, through PVDR’s adoption training program, a second chance.

On Peaceful Valley’s sprawling, 172-acre ranch in San Angelo, Texas, Zac Williams, Vice President of Off-site Operations at PVDR, walks his dogs through an open field of jennies, or female donkeys. He watches the equines closely, looking for burros with a maternal instinct that kick and bray, while taking note of the ones who seem a little too down to cuddle.

Williams isn’t an animal psychologist, but he just as well could be. As one of the leaders of PVDR’s Texas Guardian Donkey Program, he has a keen eye for which jennies hold the potential to become livestock protectors.

“I watch to see which ones come after the dogs,” says Williams. “I’m looking for a little bit of crazy, but not batshit crazy.” Those donkeys, he explains, are sent to one of PVDR’s many vast sanctuaries, where they can exist in peace (and, after they’ve been gelded, even more peacefully) for around $200 per animal per year—a fraction of the annual cost of keeping a donkey in federally-run holdings.

Once he’s weeded out the batshit burros, along with nuzzle-happy donkeys that will make great cuddly companions, Williams sends his group of promising talent into the first trial: forced bonding. He places them in a pen with a few older goats and watches to see if they’ll become aggressive over food or pick on them “just because they can.” Only the non-bullying burros move onto phase two, where they’re placed in larger pens with goats, kids (babies of the goat variety), and miniature cows. “At this point … we’re also watching to see how they interact with the kid goats,” says Williams. About three weeks into their training, if all is well, the donkeys enter the final phase. At this point, he lets them loose in big, open pasture environments and watches to see if they stick with the livestock like a watchful guardian or abandon the herd to do their own thing.

Training a guardian donkey is no small task. According to Williams, it takes between 30 and 40 days to train a single donkey, but it’s ultimately worth it, with 95 percent of the donkeys adopted out as guardians doing their job successfully. The growing guardian-donkey market seems to have picked up on this. As of now, the waiting list to adopt one from Peaceful Valley’s training program extends until the end of 2019.

Perhaps it’s difficult to imagine placing the lives of one’s sheep or cattle in the hooves of a donkey. But according to Janet Dohner, author of Livestock Guardians, donkeys often don’t need the same extent of training and specialized care as a guardian dog. More importantly, they’re effective. “We’ve discovered [that] they’re aggressive to canines and coyotes and naturally very protective.”

The donkey may not seem like fearsome fauna, but they’ve been known to take on coyotes, foxes, and bobcats. While other animals, such as horses, more frequently flee from predators, donkeys stand their ground. A 1989 University of Nebraska report describes a guard donkey “fending off three coyotes trying to attack a group of sheep bunched up behind the donkey at a fence comer.” The report states, rather triumphantly, that “the donkey was successful in this effort.”

But Dohner is just as quick to point out that guardian donkeys aren’t right for everyone. For people who are dealing with bigger predators such as wolves, bears, or mountain lions, a donkey itself could be prey.

The use of donkeys as livestock protection animals is a fairly recent development in the United States, but donkeys have taken on similar roles around the world for years. Amy McLean, an equine scientist and lecturer at UC Davis, has studied the use of donkeys in over 20 countries. She’s witnessed the informal use of guardian donkeys throughout Europe, Central and South America, and parts of Africa. For farmers on the move, donkeys serve a dual purpose as both pack animal and guardian. “You tend to see this, particularly in pastoral communities in Europe where there’s a lot of sheep production. Often they’ll even place the small lambs in carriers on the donkeys.”

So why is the donkey often seen as little more than the butt of jokes, an invasive species, or a nuisance for NASA? Perhaps its stubbornness has been mistaken for stupidity. “They’re actually highly intelligent,” says Meyers, “way smarter than a horse—and I’m not just saying that because I’m a donkey guy.” He notes that while other animals have historically been trained through systems of reward and punishment, donkeys are a little different. “He has to do it through trust, and [wanting] to do it.”

And, once you have a donkey’s trust, you’re likely dealing with a surprisingly sweet animal. On a recent recon trip into Death Valley, Meyers spotted a wild jack munching on some grass against the backdrop of a magnificent California sky. Bewildered by the sight, he crouched down with his camera to get both the donkey and the rising sun stretching behind it. Startled by the noise, the jack charged full-force at him.

Of course, this wasn’t Meyers’s first rodeo with rattled burros. “I waited until he got right up on me, and I just stood up, and kind of picked his front hooves off the ground with my shoulder,” he recalls. “He just froze, and after a few minutes he slid down and stood there, looking at me. Then we were best friends.” Meyers slung his arm around the burro, and the two embraced like old pals for long enough to snap an even better picture. Just a quick glance at the photograph of Meyers and his furry friend is evidence enough that, at the end of the day, these creatures are indeed kind of like big dogs—just a bit more complex, a bit more invasive, potentially combative, and, until now, not nearly as adoptable.

“My goal isn’t to completely eradicate wild burros,” says Meyers. “I do this for a living, and I still get goosebumps when I see one. But when they’re not managed, and they become a nuisance—that’s when rash decisions are made and bad things happen.”

To save these equine “big dogs,” they don’t necessarily have to become man’s best friend. But at least, with a little management, and a lot of training, they can be more widely seen as something beyond mere interference.

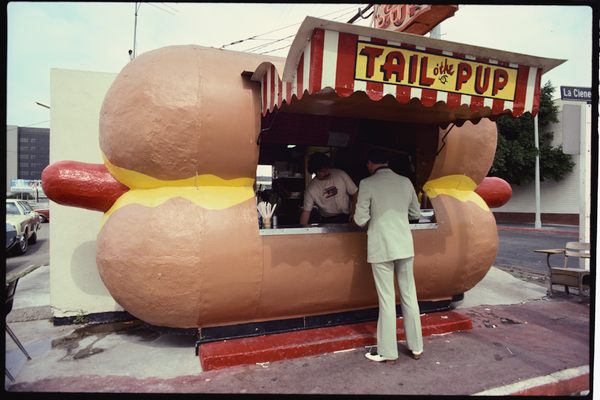

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook