Wrapping Armchairs in Wire, and Other Childhood Attempts to Travel in Time

H.G. Wells, author of The Time Machine, likely had all kinds of ideas about time travel as a child. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

What kid doesn’t, at some point, want to go forward or backwards in time? To skip ahead to when he’s allowed to buy his own candy, or to go back to before she broke a family heirloom, or dinosaurs went extinct?

Most people tend to pause and shake their heads when asked whether they believed in time travel as a child. Some say that they dreamed about it and wished it was real, but didn’t ever imagine that crossing the boundaries of time and space was a thing that could actually happen. But then five or 10 minutes go by, and the same people start recalling certain moments. “Well, actually…”

There are two camps among these early time travel disciples: those who believed transportation into the past or future would happen by chance, and those who thought such a passage required a special machine or mechanism.

To rewind or fast forward? That is the question. (Photo: Rodger Evans/flickr)

Aaron Lewis, who is currently working on a PhD in biochemistry, falls into the latter category. “I remember taking a Sharpie to a cardboard box and making it look like a TARDIS, which is a police call box [in Doctor Who],” he says. “I remember getting inside that and spinning around; I had some idea that moving fast could slow down time.”

When this was unsuccessful, Lewis, then seven years old, turned to a chair. He’d always thought this chair would make a suitable seat for a proper time machine, à la H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. “But I didn’t have a combustion engine or anything like he did, so I wrapped it up in copper wire because metal coils make electricity in a magnetic field.”

“I figured my time machine would be powered by the field of the earth itself. So how could it not work? Imagine a little boy sitting with eyes very hard shut, very uncomfortable on a wire-wrapped armchair.”

Lewis grins. “Thank God electricity doesn’t work like that. Because if it had been inducting I would have electrocuted myself.”

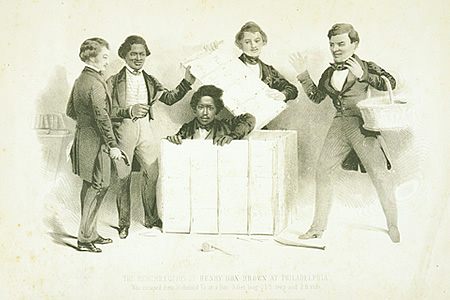

Is this an 1850s illustration of human mail or a time travel machine? Hard to say. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Like Lewis, almost everyone surveyed seems to have developed their interest in time travel under the influence of literature. At formative ages, they read books that transported them to a different era, and that subsequently encouraged them to try stumbling through the bushes into another land, or going down a slide until it rocketed them back in time.

Few of us, however, were as ambitious as Lewis in our forays into time exploration. Some of us, in fact, even feared it—making preparations in case it took us by surprise.

“After reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I definitely used to get slightly nervous whenever I hid inside this large standing wardrobe we had in the basement, during hide-and-go-seek,” admits Atlas Obscura deputy editor Rachel Doyle. “I used to take stuff in there with me, just in case I ended up in another world and might need it.”

Others of us may have deliberately sat inside closets in the hopes of meeting Mr. Tumnus at that snow-dusted lamppost. Sadly, none surveyed were successful, either at that or in managing to fast forward to the end of middle school.

If you go fast enough you’ll blast into the future! (Photo: Karensams/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Adults now in their 20s, 30s, and 40s tend to have similar reference points for their notions of traveling through time, mentioning classic books like A Wrinkle in Time, The Phantom Tollbooth, and the works of C.S. Lewis as the main inspirations for their fantasies.

Others tend to pinpoint popular series like Choose Your Own Adventure, the Magic Tree House, and the Harry Potter books, singling out Hermione Granger’s Time-Turner necklace in The Prisoner of Azkaban.

As far as attempting the act of time travel themselves, films on the subject seem to inspire kids to do this less than reading books does. No one I spoke with had watched Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure and then attempted to ace a school project with the help of a time machine, or tried to spot earlier versions of their parents, as in Back to the Future.

What’s waiting on the other side of the wardrobe. Make sure to bring a scarf! (Photo: © Copyright Rob Farrow CC BY-SA 2.0)

Imagining a book’s characters, without seeing other depictions of them, seems to breed resourcefulness. After reading The Time Garden, by Edward Eager, Atlas Obscura staff writer Sarah Laskow nosed around outside for some thyme and tried rubbing it vigorously between her fingers. In the book, the main characters transport themselves through thyme, and time, to visit the Underground Railroad and Victorian England.

As romantic as Victorian England sounds, for some kids, the idea of time travel involved some very real obstacles. Urvija Banerji says that after seeing a play in fifth grade in which children traveled back in time to medieval England, she remembers thinking about how, being Indian, she would not be able to fit in at all. She reconsidered, and hasn’t pursued time travel since.

A poster for the 1960 movie adaptation of H.G. Wells’ classic book. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

That’s not the case for a handful of others who, long past childhood, have kept the dream alive. “It’s real, 100 percent, no doubt about it,” says Ric Best, a trader. He’s not talking about wrapping copper wire around an armchair or rubbing thyme, but about harnessing the powers of quantum mechanics and the multiverse.

Still, realistic technologies will never be as romantic as rubbing thyme, or the books we read as children that may have given us the idea to do so. Some things like that are simply timeless.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook