Mongolia’s ‘Forbidden Zone’ Is Guarding an 800-Year-Old Secret

Is the vast Khan Khentii Strictly Protected Area the final resting place of Genghis Khan?

When you drive north toward Ordos City in China’s Inner Mongolia province, you can’t miss the Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. The massive complex, rebuilt in the 1950s in the traditional Mongol style, houses genuine relics and is an important sanctuary for the shamanic worship of the legendary Mongol leader. But the Khan’s tomb is properly called a cenotaph—a monument to someone buried elsewhere—because it is empty.

An Unmarked Grave for the Universal Ruler

While we can be certain his mortal remains are not there, we’re completely uncertain as to where they might be. And that’s odd. In life, he was the most powerful person on Earth. He was the Universal Ruler (“Genghis Khan”) of an empire that would eventually stretch from the Pacific Ocean into Eastern Europe, encompassing large swaths of present-day China, Russia, and the Middle East. Yet his grave is unmarked and remains undiscovered.

This is by design. Despite his exalted status, Genghis Khan retained the frugal, itinerant lifestyle of his youth, and indeed of most Mongols. So it makes sense that he would want a humble, anonymous burial in his homeland. “Let my body die, but let my nation live,” he is supposed to have said.

Early in life, the Khan was a boy named Temüjin, born near Burkhan Khaldun, a sacred mountain in the northeast of present-day Mongolia. He grew up in deep poverty and constant peril. The mountain was of great spiritual importance in his formative years, and thereafter. Burkhan Khaldun would offer him refuge, a place to pray to the sky god Tengri, and a backdrop to hunt. On one of those hunting trips, The Secret History of the Mongols tells the story of Genghis Khan resting under a tree, exclaiming: “What a beautiful view. Bury me here when I die.”

Death came to Genghis Khan in the summer of 1227 on the upper reaches of the Yellow River. Although nearly 70 years old, Khan was still on the warpath, crushing the Tangut kingdom into submission. The Secret History, the only native and near-contemporary source of information on the 13th-century Mongols, is as reticent about the Khan’s death as it is detailed about his life. Perhaps this is because illness and death were great taboos in Mongol culture. As such, we are left mainly with legends and speculation.

Lightning Strike, Arrow Wound, Severed Manhood?

We don’t really know how Genghis Khan died, but that didn’t stop an early European emissary to the Mongols from reporting that the Khan had been struck by lightning. Marco Polo, however, said the Khan had died from an arrow wound to the knee. Other commentators claimed he had been poisoned, or killed by a magic spell cast by the vengeful Tangut king. The most outlandish story is that the Tangut queen, seized by the Khan as a spoil of war, concealed a device within her person that severed the Khan’s manhood when he took possession of her, leading to his torturous demise.

A less sensationalist source merely relates how the Khan’s wife Yesui prepared his body for burial in the simple way in which he had lived: dressing him in a white robe, felt boots, and hat. She then reportedly wrapped the body up in a white felt blanket filled with fragrant sandalwood, the blanket bound with three golden straps. The funeral procession heading back into Mongolia included a riderless horse that carried Genghis Khan’s empty saddle.

There are also crueler and more detailed versions of the story. Some say the soldiers in the funeral cortege killed every living thing—human and animal—they came across on their 40-day journey. It’s also said that after the Khan was laid to rest in his unmarked grave, a thousand horsemen trampled over the area to obscure the grave’s exact location. Afterward, those horsemen were killed. And then the soldiers who had killed the horsemen were also killed, all to keep the grave’s location secret.

One story mentions that a baby camel was buried with the Khan, so its mother would always be able to lead the Khan’s family to the exact location of his grave. And another version says that a river was temporarily diverted to hide the grave (as was done for the Sumerian king Gilgamesh, and the Visigothic king Alaric).

Heirs Presumptive to the Mongol World Empire

In the absence of hard evidence—or a bereft mother camel as a homing device—many countries have asserted, on the flimsiest of evidence, that Genghis Khan is buried on their territory: not just Mongolia and China, but also Russia and Kazakhstan. It’s an attempt by each of those countries to symbolically claim they are the legitimate heirs to the world empire he founded.

But there is one piece of solid evidence: Right after Genghis Khan’s death and burial, a “Great Taboo” (in Mongolian: Ikh Khorig) was pronounced on an area of about 93 square miles (240 square kilometers) around Burkhan Khaldun. This meant that entrance to the area, which is hard to access due to natural features anyway, was now strictly forbidden to anyone upon pain of death—except for Genghis Khan’s family if they had another relative to bury.

Of course, the Great Taboo could itself be an elaborate ruse to divert attention away from the Khan’s actual burial site. If so, it’s an extremely long-lasting one. The taboo was enforced by a guardian tribe called the Darkhad, who were in exchange exempted from taxes and military service. Their descendants maintained the taboo for almost seven centuries, until 1924 when the Mongolian People’s Republic was established.

Pristine and Undisturbed for Centuries

For all that time, the region has remained pristine and undisturbed, its forests, steppes, mountains, and valleys untouched by humans. The only trails are those made by animals. It is essentially the same landscape as it was in the 13th century and many centuries before that.

That’s because even the Communists weren’t comfortable simply “deconsecrating” the area. Afraid it could become the focal point for Mongolian nationalism, they renamed it a “Highly Restricted Area” and surrounded it with an additional 3,900 square miles (10,000 square kilometers) of “Restricted Area” under military supervision, which housed air bases, weapons storage facilities, and artillery ranges.

Joseph Stalin, in his obsession to gain a better understanding of two of Asia’s most famous conquerors, had Timur’s tomb opened, and he also sent several unsuccessful expeditions to Burkhan Khaldun to locate Genghis Khan’s grave.

It is alleged that the exhumation of Timur (a.k.a. Tamburlaine) unleashed a curse upon the Soviet Union. Three days later, the Nazis invaded. The Soviets’ luck only turned after they reburied Timur in November 1942. Soon after, they were victorious at Stalingrad. So perhaps it was a good thing, at least for the Soviets, that Stalin’s explorers never found Genghis Khan’s grave.

Communism in Mongolia ended in the late 1980s, as did most of the limits on entry into the Highly Restricted Area. Drawn in by the enduring mystery of the Khan’s missing grave, foreign archaeological expeditions started exploring the area. In the early 1990s, a Mongolian-Japanese research team used ultrasound to identify more than 1,300 locations of Mongol nobles’ graves in the area.

A New Protective Paradigm for the “Great Taboo”

Other expeditions followed, some believing that Genghis Khan may be buried near the summit of Burkhan Khaldun. However, it is unlikely that the Mongolian government would ever allow actual excavations to prove or disprove these theories. The thought of opening the last resting place of their national hero is abhorrent to most Mongolians.

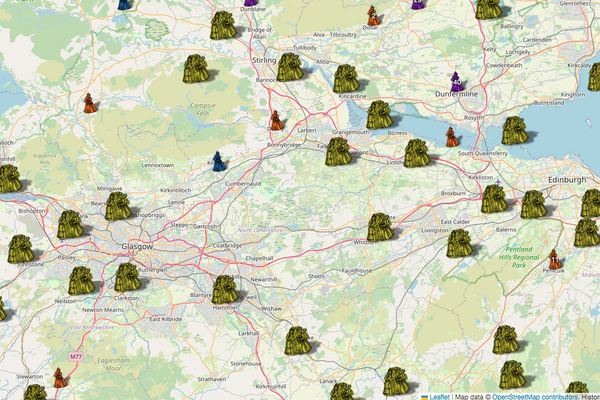

Meanwhile, the sacred mountain and its pristine surroundings have found a new protective paradigm. It’s no longer tribal guardians or Communist soldiers that restrict access and development in the area. UNESCO has listed the area as a World Heritage Site, called the Burkhan Khaldun Sacred Mountain, most of it managed as the Khan Khentii Strictly Protected Area (4,740 square miles, or 12,270 square kilometers). The regulations for this area state that any activity on Burkhan Khaldun mountain itself, other than worshipping rituals, is traditionally forbidden.

Further information on Khan Khentii is hard to find, as are maps of the Strictly Protected Area. One of the few available comes from the UNESCO website, above. It is almost as if someone doesn’t want this area advertised, described, or accessed. And Genghis Khan would approve of that, as would most Mongolians, and anyone who thinks that some mysteries are better left unsolved.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook