Creating a Bacteria Painting Is an Elegant But Dangerous Art

The living germ artworks must be destroyed after creation.

On an early February morning in 2024 at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, David Westenberg dons safety goggles and latex gloves. The bespectacled microbiologist and professor of biological sciences for the last 27 years gently removes a series of test tubes containing strains of Escherichia coli from a crisp freezer set to minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit. These E. coli samples have been inserted with genes that will allow them to produce pigment. Westenberg is about to culture a microscopic organism with a 25 to 40 million-year-old ancestry—though not for any usual scientific reasons.

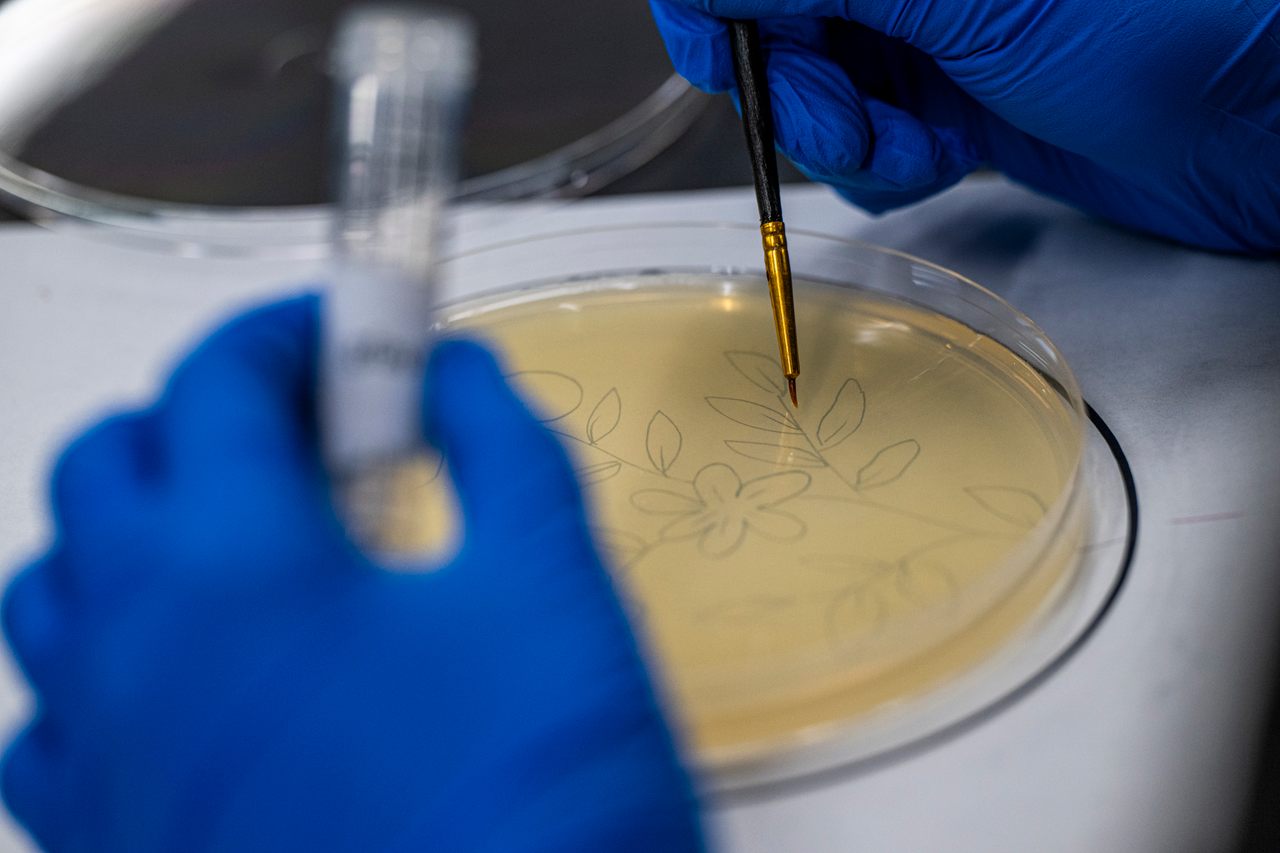

Using a wooden stick, he carefully spreads these strains onto a sterilized petri dish containing a nutrient-enriched antibiotic powder and a solid layer of a gooey substance called agar. This is a fertile mix that will allow the bacteria to grow and produce pigment over the next few days. Once they’ve grown, he’ll sterilize individual strains by suspending them in a saline solution. Then, and only then, will they be ready for his students to use in a Valentine’s Day-themed activity centered around agar art, otherwise known as microbial art, or the process of creating living paintings with bacteria.

There’s no comprehending agar art without first understanding what agar is. The white, gelatin-like substance is gleaned from red algae and can be used for cooking purposes, particularly for making desserts. It’s especially coveted by microbiologists for its thickening and stabilizing properties, which creates a solid growing area where, with the help of nutrients, bacteria can be cultured and studied. Agar art, therefore, is the practice of using this jelly-like medium to culture pigmented microbes and manipulate them into elaborate designs and patterns, bridging the worlds of arts and sciences with the flick of a paintbrush.

But if it’s not done right, there are some serious dangers involved in the art, including contamination and spreading disease to the general public.

Microbial art has actually been around for nearly 100 years. It’s the brainchild of Scottish physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming, best known for discovering the world’s first antibiotic, more commonly known as penicillin, in 1928. Fleming, an amateur artist, had been making “germ paintings” prior to his world-altering discovery, according to Kevin Brown, the curator of the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum in London.

Although it’s unclear exactly when and how Fleming came to use bacteria for painting, his living paintings included sketches of buildings, a nursing mother, and bacteriophages in a boxing match. He once reportedly showed a microbial painting of a guardsman to George V and Queen Mary when they came to an opening of new medical school buildings, which left the Queen “unimpressed,” says Brown.

While Fleming is largely considered to be the pioneer of microbial art, the microbiologist and his contemporaries ironically didn’t think much of his creations. “They were a bit of fun for him and amusement for his family and friends, and not exhibited,” explains Brown. “There was no reason why anyone would have known about them. They were curiosities rather than works of art.”

Those “curiosities” therefore remained on the fringes of most people’s consciousness for nearly a century. Then, in 2015, the American Society of Microbiology (ASM) set up an annual agar art contest, which launched the scientific art form into the international spotlight. It has since ballooned to include contestants from more than 30 countries, with various themed competitions for professionals, amateurs, and even children taking place in the fall. Winners can earn cash prizes up to $200 and will have their art displayed permanently on the ASM’s website. For many microbiologists, the creation of this contest marked the first time they were introduced to agar art.

Microbiologist Balaram Khamari, an assistant professor in the department of biosciences at the Sri Sathya Sai Institute in Bengaluru, India, first started agar art in 2019 after learning about the ASM art contest through a colleague. “The experience of creating something interesting with my boring daily work, involving a tireless culture of bacteria, was just out of this world,” he says. For Khamari, a skilled artist since childhood, agar art became a new medium through which he could express his creativity. “The excitement and unpredictability of the result of my art gives me an adrenaline rush, which is unparalleled.” In 2020, Khamari won the second place prize in the ASM’s traditional category contest for his “Microbial Peacock,” a detailed peacock drawing used to represent his native country, and he’s continued to hone his agar skills over the years.

Westenberg’s first foray into agar art began some 15 years ago with a bioluminescent bacteria called Photobacterium leiognathi. He used it to create glow-in-the-dark petri dish birthday cards and nightlights for his daughter while she was away at summer camp. “The hazards of being the child of a microbiologist,” he jokes. Today, he primarily works with E. coli and holds various agar activities throughout the year for his students, as well as general public outreach events to foster scientific curiosities in all ages and disciplines.

However, Westenberg must take serious safety precautions to prevent the potential spread of harmful bacteria.

On the day of his events, he sterilizes his fine-tipped paint brushes and pigmented bacteria strains. He then places the strains, which are of 11 different colors, into sterilized plastic test tubes that his students will use to paint.

Students first draw their images on a piece of white paper and then place their petri dishes on top to begin tracing their designs with paint brushes. Their work is virtually invisible, as the colors will only emerge and bloom once the completed petri dishes are suspended upside down in a 98.6-degree Fahrenheit incubator for 24 to 48 hours. This temperature, the same as the human body, is optimal for growing E. coli, explains Westenberg. Once the colors have fully matured, they can remain vibrant for months. As they fade, they’re securely disposed of in an autoclave, a machine that uses pressurized steam to kill bacteria. This safety precaution is essential, says Westenberg, as it prevents antibiotics from being released into the environment, which can lead to antibiotic resistance.

Though Westenberg is a professional, amateur microbiologists have also taken up the craft. Although this has generally been welcomed and encouraged, there are some, such as Brown, who express concerns. “The production of such works demands the skills of the bacteriologist as much as the eye of the artist. Amateurs working with bacteria could pose dangers to themselves and the wider world,” explains Brown.

Westenberg takes a more temperate response when it comes to the rise of amateur biology, which he’s coined as a scientific “DIY culture.” He’s mostly fascinated by the professional-grade labs that are popping up in people’s garages and basements, as they signal a willingness to pursue scientific interests regardless of the often expensive, inaccessible barriers to learning. However, he acknowledges that microbiology should always be taken seriously. “Bacteria is not something to be cavalier about. There’s room for more people, but we just need to be cautious about how we proceed. I’m not alarmed, but I’m certainly cautious.”

There’s always an inherent risk when handling bacteria, which is why safety precautions are paramount during Westenberg’s activities. The use of latex gloves and safety glasses, as well as repeated hand washing, are mandatory in his classes. He also keeps spray bottles filled with bleach and paper towels near workstations in case of spills. And he only works with non-virulent and non-disease-causing pathogens such as E.coli that are categorized as risk group one. Some of the professional ASM contestants work with microbes from the remaining three risk groups, he says, which is beyond what he feels comfortable doing with his students.

“I feel comfortable working with [bacteria], but I don’t want to expose others because I don’t know their immune systems. I think it’s best to err on the side of caution,” he says, adding that even bacteria considered to be the least dangerous to humans can be harmful in some capacity.

Regardless of potential safety concerns, Westenberg champions agar art for its ability to raise awareness of the beauty and diversity of the oft-overlooked microbial world. It’s a crucial point he always hopes to impart to his students. “Most people think of bacteria as being bad, unhealthy [or] gross, but as a microbiologist, I know that the vast majority of bacteria are harmless and often beneficial,” he explains. “At the same time, we have to be aware that there are harmful bacteria out there, and we can’t always tell the difference.”

In many ways, agar art’s increasing popularity is another creative iteration of microbiologists’ attempts to reverse the negative stigma bacteria have earned since humans first learned of their existence. For Westenberg, it’s been a way to bring people from all backgrounds and ages together to learn how to practice a healthy dose of cautious respect for the organisms that have shaped, and continue to shape, the world we live in.

“Bacteria have been around since the beginning of time, they were the first living organisms. They’ve had billions of years to evolve. They’ve covered every niche on the planet, they do amazing things for our environment, and we’re learning now how important they are for our own health,” he says. “We don’t have to be afraid of them. We just have to respect them.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook