The Moldy Medallions That Preserve Penicillin’s Past

Alexander Fleming, the researcher who discovered it, started culturing commemorative keepsakes.

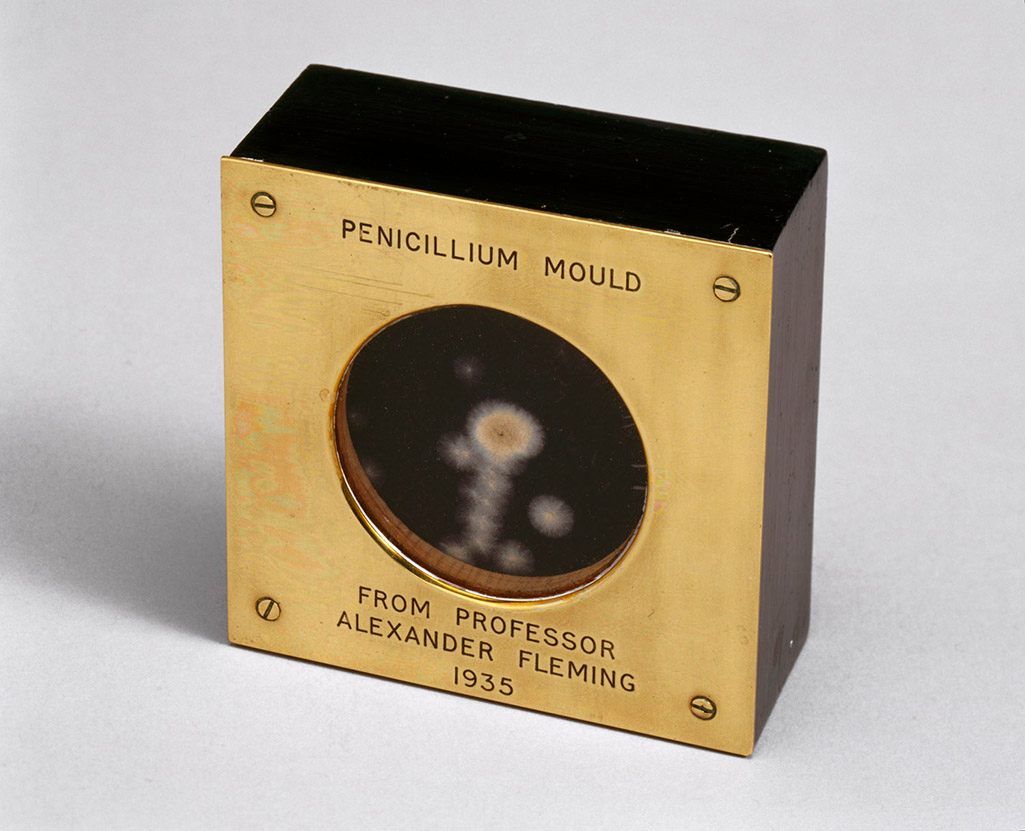

The wood box fits in the palm of a hand. The brass medallion inside it is the size of a sand dollar, or the bottom of a cup. It looks vaguely geological—like a fossil, sandy brown and eggshell white—and rests on a bed of velvet.

At first glance, “it’s almost like you’re opening a jewelry box,” says Anne Garner, curator at the New York Academy of Medicine Library. “Then here’s this bacteria.”

The medallion was made by Alexander Fleming, the Scottish microbiologist who first stumbled upon the mold that would become the basis of penicillin. Once he started fashioning little objects to commemorate his discovery, he couldn’t stop himself from churning them out.

Fleming’s discovery of penicillin was the product of luck and a slovenly streak. In 1928, he was working in the inoculation department at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, where he researched the treatment of boils. One night, he left his workspace in disarray. Some accounts say he piled his dishes in the sink, while others maintain that he left them strewn across the lab bench; some recount that he left town for weeks, and others suggest that an assistant simply cracked a window overnight.

What’s certain is that his untidy habits turned out to be fortuitous. Fleming had been studying Staphylococcus, and when he returned to the lab, he spotted yellow-green mold growing on one of the cultures where he’d smeared the bacteria. It looked like the whole thing was ruined. But before he pitched it into the garbage bin, he took a closer look. There were a handful of patches from which the bacteria seemed to have been scrubbed. Where the mold grew, it turned out, Staphylococci didn’t.

Fleming dubbed the fungus Penicillium notatum. Over the next few years, he performed a few experiments and determined that it wasn’t toxic. But he then moved on to other projects, and it wasn’t until the 1930s and ’40s that two other scientists, Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Howard Walter Florey, fully investigated the mold’s potential as an antibiotic and began to scale up production of penicillin. In 1945, the lot of them—Chain, Florey, and Fleming—shared the Nobel Prize, “for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases.”

Once he achieved laureate status, Fleming couldn’t stop making moldy medallions. Fleming used portions of the original culture to grow more on slips of paper, then pressed these between lenses from his brother, an optician. The result was a transparent display with the benefit of a tight seal.

It’s unclear exactly how many were in circulation. Fleming described them as rare, but also appeared to consider them to be a kind of social currency to mint when it suited him—which it often did. He handed them out to esteemed colleagues and leading ladies, including Marlene Dietrich. (“It almost seems like a flirtation,” Garner says. “Like, ‘Here, have a culture.’”) The one in the Academy collection was a gift from Fleming to the American actress Ruth Draper, whose father—a prominent New York City physician—donated it to the collection. Fleming also gave moldy keepsakes to President Roosevelt and the Pope, Garner adds, as well as members of the British royal family.

The gifts weren’t always well received. By the time Fleming presented one to Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, in a June 1954 celebration commemorating the 25th anniversary of the discovery, the royals were already flush with bacterial cultures. It was the second medallion that Fleming had gifted the prince in the span of six months, and the Queen Mother already had one of her own, too. Philip was said to quip that maybe he had all the bacterial cultures he needed, telling one of his household officers, “every time I meet this chap Fleming, he gives me one of these bloody things.”

Garner suspects that Fleming created roughly 20 medallions in all. These days, at least a few people seem glad to have them—or at least are willing to pay for the privilege. A medallion held by Fleming’s niece netted $14,592 at auction in 2017, and the Pfizer corporation bought one from Sotheby’s for $35,000 in 1996.

Though this type of object is more immune than, say, books are from being damaged by moisture and temperature fluctuations, the Academy still houses it in a vault equipped with environmental monitoring tools. “It’s one of our more secure locations in the building,” Garner says.

This September, the medallion will be on view as part of the exhibition, Germ City: Microbes in the Metropolis, a collaboration between the the Academy and the Museum of the City of New York. Meanwhile, Garner occasionally brings it out to show to library visitors. “People are often really moved by it,” she says. “People have cried in front of me. It’s an amazing moment of medical progress.”

Even in the era of antibiotic-resistant infections, it’s hard to overstate the drugs’ contributions to prolonging human life. (Penicillin also kept Fleming himself afloat during a bout of pneumonia in 1953.) “You’ve probably taken penicillin in some form or another, or had a kid or a mother who took it,” Garner says. Hundreds of millions of prescriptions have been dispensed over the decades, and the medallions are a tangible way to consider how it all began—by accident, in a petri dish.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook