In the 1890s, Female Medical Students Embroidered a Yearbook on a Pillow Sham

The newly minted doctors had deft handiwork.

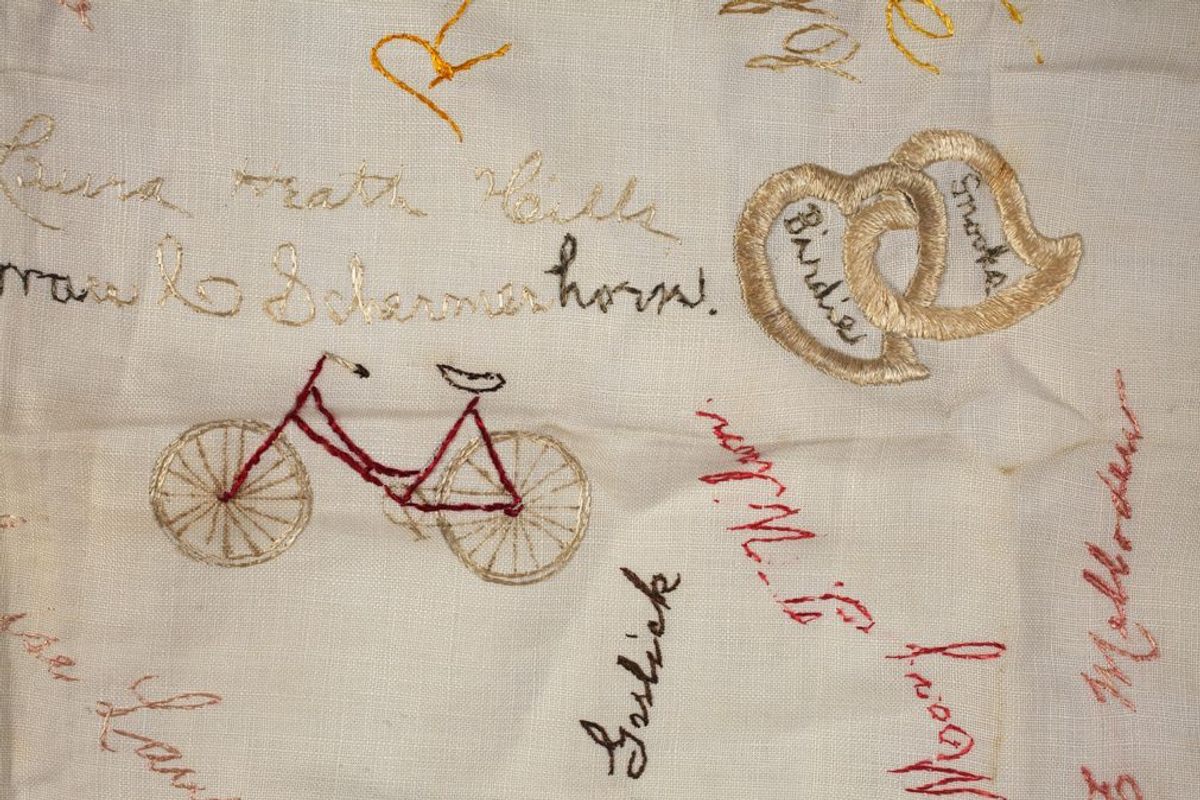

In 1896, a group of women in Philadelphia embroidered a white pillow sham. It was crisp and creamy, with a frilly, ruched border edged with eyelets and tiny white flowers. There was nothing especially unusual about the pillow covering—at least until these women got their hands on it.

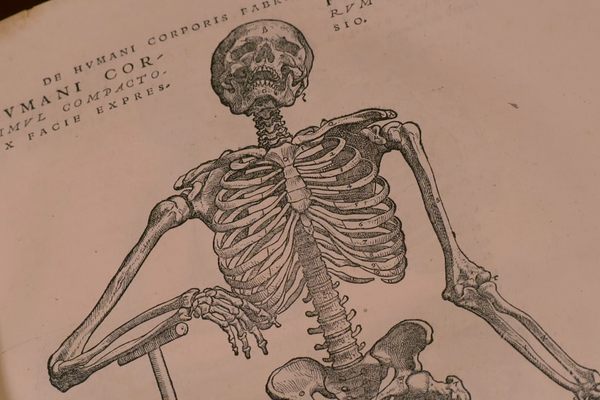

They stitched their signatures across it, in tidy loops and swoops of red, yellow, and black. And around their names they embroidered some symbols of their trade: a doctor’s bag, a thermometer, a skeleton, a figure, unsmiling and broad-shouldered, decked out in a cap and gown.

One side of the sham read, in elaborate crimson letters, “W M C of P.” The embroiderers were newly minted physicians from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, and they were ready to leave their mark.

The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania—which began its life, in 1850, as the Quaker-founded Female Medical College of Pennsylvania—was among the earliest American institutions to grant degrees to female physicians. The school eventually went coed, and was rebranded as the Medical College of Pennsylvania, then merged with Hahnemann University (formerly known as Hahnemann Medical College), and eventually became part of Drexel University. The sham is now in the collection of Drexel’s Legacy Center. There, archivists store it in a large, flat box, and it sits alongside photographs, letters, journals, and other ephemera that narrate the experiences of some of America’s first female MDs—both inside and outside the hospital.

Many women of the time were eager to become doctors. “Medicine attracted more women votaries in the 19th century than any other profession except teaching,” writes historian Regina Morantz-Sanchez in the anthology Sickness & Health in America, Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health. According to Morantz-Sanchez, by 1900, there were several thousand female physicians in the United States. (Women still only made up only a single-digit percentage of practicing doctors, and according to the American Medical Association, this held true until well into the 20th century.)

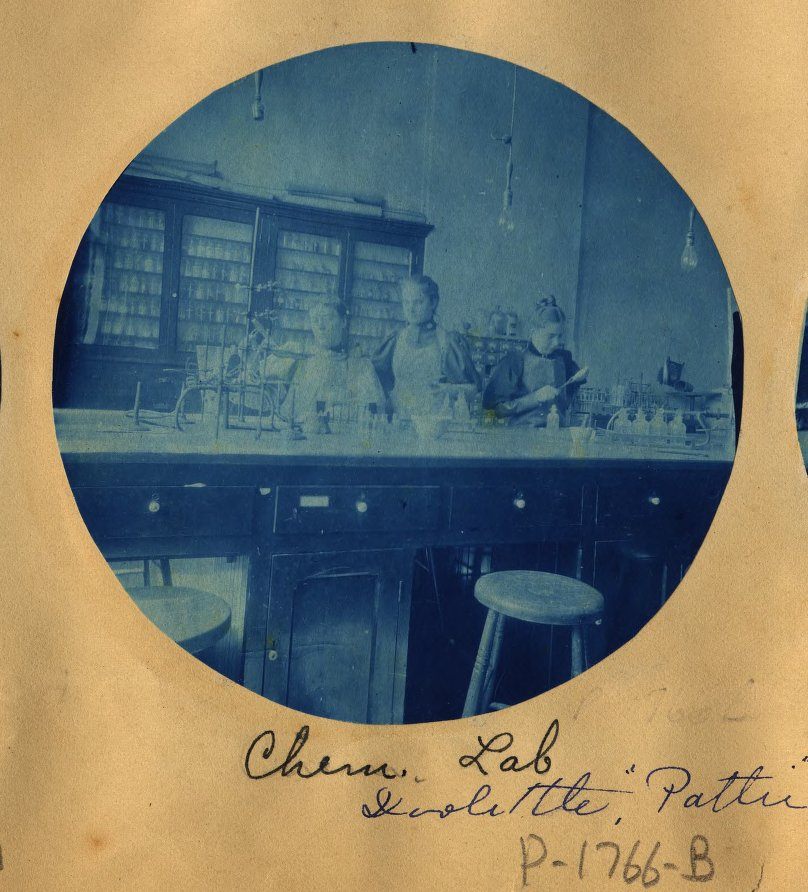

At the Woman’s Medical College, at least, the curriculum spanned anatomy, chemistry, physiology, hygiene, and more. Students scribbled notes in lectures, peered through microscopes, bandaged wounds, and dissected cadavers while wearing waist-nipping, floor-grazing dresses. On one busy February day in 1893, a student told her diary that she had spent four hours in the laboratory, followed by three hours of classroom instruction, and then three hours with her cadaver. But training—and possible career paths—often differed for men and women.

At the time, female doctors were often shunted toward obstetrics and maternal health; in an era in which health reformers had appointed women the stewards of family well-being and hygiene, female physicians were frequently trained mostly to treat other women and their children, with a focus on preventive care. So students at the college paid house calls to pregnant patients, and collected urine samples and performed pelvic exams outside the hospital. The male students studying nearby were way less likely to do so. Prior to the 20th century, writes nephrologist and author Steven J. Peitzman in a history of the college, “such practical maternity work occurred rarely in all-male American schools, from many of which it was possible to graduate without ever having delivered a baby.”

But some female doctors delighted in the advantages of a focus on preventative care and intimate access to patients’ lives. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to receive a medical degree in America, and her physician sister, Emily, once remarked that female doctors bridged public and private worlds, “occupying positions which men cannot fully occupy, and exercising an influence which men cannot wield at all.” And Prudence Saur, trained at the Woman’s Medical College, argued that female physicians had a particular potency: “How much more God-like, to prevent as well as cure!”

The class of 1896 made a particular point to document their lives with their teachers, patients, peers, and cadavers. The class historian, Laura Heath Hills, collected their experiences in a notebook, “Souvenirs of the Class of 1896.” Its handwritten pages include musings about whether a premature infant would survive the night in her incubator, and how the class president had earned a plum position by touching “the arthritic spot” in another doctor’s heart.

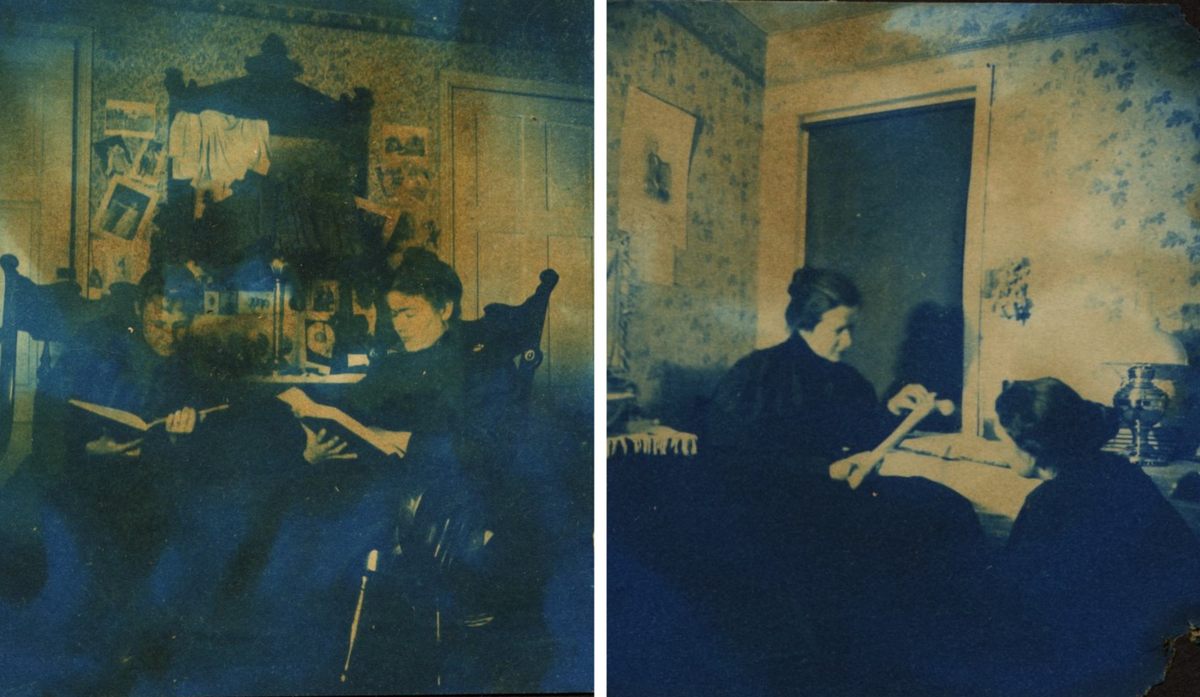

The doctors-to-be also chronicled their lives outside of the classroom, but medicine was rather all-consuming. The students snapped photos of one another poring over brick-thick books, or scrutinizing a bone against leafy wallpaper. They bonded in their snug bedrooms and over shared meals, and they pulled pranks, such as smuggling skeletons into their dormitory and dressing them up in jaunty jackets and caps.

The embroidered sham, which the archivists believe may have been presented to the dean as a gift, nods to these slivers of life away from scalpels and forceps. In neat needlework—which notably resembles sutures—the students crafted little flowers and birds, and placed two names in interlocking hearts. They added two bicycles, as well, maybe a reminder of how they navigated campus, or perhaps as a celebration of setting out down a new and unfamiliar path, with the breeze in their hair.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook