A Look Inside Florence’s Strangest Archive

For six centuries, the Corsini Family has recorded everything that’s ever happened to them.

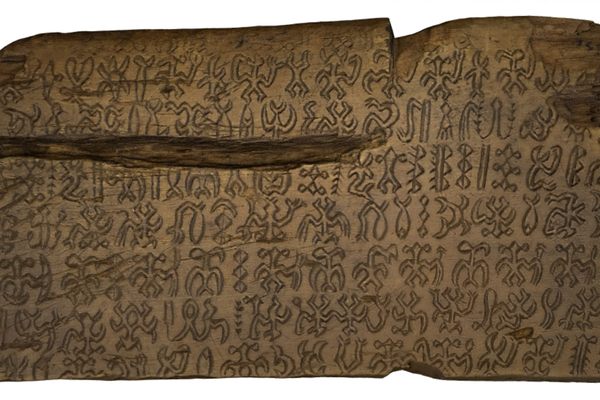

One of six archival rooms on the first floor of Tuscany’s Villa le Corti. They hold the Corsini family’s archived history, from the 1360s through the 1960s. (Photo Courtesy New York Times Style Magazine)

For most of us, understanding our pasts requires a bit of detective work—piecing together family stories, yellowing scrapbooks, and saved letters to form an idea of what life was like for those who came before.

But what if you had more than just scraps and pieces? What if every relative you ever had kept a diary, and they were all in one place?

One Florentine family has managed just that. In a recent feature in T Magazine, reporter Tim Parks visits the Villa le Corti in Tuscany, which houses the Corsini family archives—4,000 feet of volumes spanning 600 years of history, painstakingly recorded in day-to-day detail.

The tradition was started in 1362 by Matteo di Nicholò Corsini, a cloth trader who, like other Florentine merchants of the time, thought it best to keep a record of his every transaction. “I… Matteo, will write down every thing of mine and other facts about me and my land and houses and other goods of mine,” he wrote.

Unlike his peers, though, Matteo managed to pass this proclivity down through dozens of generations. “For 600 years his descendants followed his example, writing down everything about themselves and preserving everything they wrote,” Parks writes.

The Villa le Corti, home of the Corsini family’s extremely comprehensive archives. (Photo: Sailko/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Flipping through the thousands of volumes yields a pizzeria’s worth of slices of life—the last will of a 14th century cardinal, the health concerns of 16th century merchants, the private notebooks of 18th century women. The medium lends the sense of history and connection a material component. “Wherever you come to in the archive you are immediately overwhelmed by an intense awareness of paper,” writes Parks:

“There is the thick sepia-toned, slightly porous paper of the 1400s and the ultrathin glossy correspondence paper of the 19th century. There are papers with elaborate watermarks, and with tiny cuts made in the 16th century to show that the surface had been disinfected against the plague. Some papers have been eaten away by silverfish; others have gotten wet and smudged.”

In the 1960s, the family stopped recording their every move, instead dedicating their archival energies to preserving what they already have. Parts of their villa are now open to visitors and scholars, and others who want to dive into a very specific library—one that houses a thin, deep core of the past.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook