A Mosque for Women Opens in Denmark, Taking a Cue from an Unexpected Source: China

Women’s waiting area at the Sixty Dome Mosque in Bangladesh. (Photo: Flickr/joiseyshowaa)

This past week, Scandinavia’s first women-led mosque opened in Denmark, joining a small community of newly-established mosques intended for and led by women, including the Women’s Mosque in Los Angeles and a planned mosque in the United Kingdom.

These efforts might be taking their cues from a surprising source: China.

In Denmark, Sherin Khankan, an author and commentator, spearheaded the effort, making the motivations behind the mosque’s establishment clear to The Guardian,”We have normalised patriarchal structures in our religious institutions. Not just in Islam, but also within Judaism and Christianity and other religions. And we would like to challenge that.

The new mosque has not been without controversy. The Guardian reports that prominent Danish imam Waseem Hussein asked a Danish newspaper, “Should we also make a mosque only for men?”

Some might respond that the majority of mosques essentially are only intended for men—women are frequently segregated by a partition or in a separate room, and some women argue that the women’s spaces tend to be inferior. Activists also point out that because imams are overwhelmingly male—in 2011, there were no female imams (imama) in America—khutbah (sermons) rarely speak to women’s spiritual lives. Women also may not feel comfortable consulting a male imam on religious or personal matters.

These issues and others mean that Khankan is not the only Muslim feminist seeking to challenge Islamic patriarchy. Journalist Asra Nomani, who in 2003 demanded the right to pray in the main prayer hall (musallah) of her mosque, has drafted an Islamic Bill of Rights for Women in Mosques, and prominent Muslim feminists were sharply critical of President Obama’s decision to visit a gender-segregated mosque earlier this month. Scholars such as Latifa Akay argue there is no religious reason for gender segregation, attributing such practices to subjective interpretation influenced by cultural norms. Instead, Akay and others believe that gender equality is very much a part of the Islamic tradition, telling Quartz, “Having women as leading figures in Muslim communities and mosques should not be seen as something new or surprising.”

Indeed, while there is generally accepted religious law prohibiting imama from leading mixed-gender groups in prayer, other practices such as excluding women from the musallah or limiting women’s roles as religious leaders are more debatable. In fact, in Chinese Muslim (Hui) communities, women’s mosques and female religious leaders have existed for quite some time.

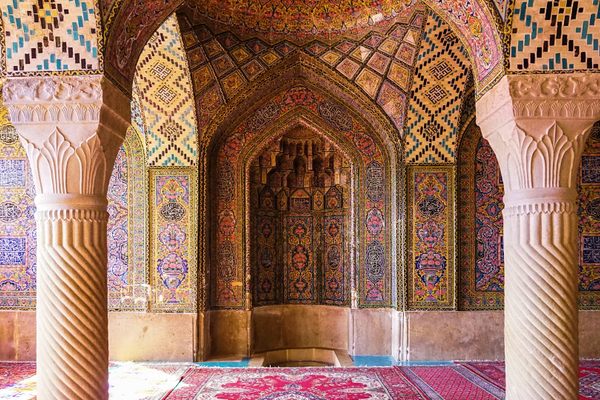

Xiaotaoyuan Women’s Mosque, Shanghai, China. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Chongkian)

In China, women’s mosques are called nüsi, and records indicate they have existed for over 300 years. The oldest nüsi still in existence—Wangjia Hutong Nüsi in Henan province—dates to 1820. Women and girls attending the nüsi are lead by female religious leaders known as ahong. The ahong’s role is varied and can include providing education, leading religious ceremonies, or providing moral guidance and counseling. Hui women even have their own religious chants—jingge—although they fell out of practice during Mao Tsetung’s harsh Communist crackdown on religious activity. Ethnologist Maria Jaschok documented how jingge are beginning to re-emerge in nüsi in a working paper:

Everyone was enthralled, particularly as none of the younger women and girls had ever heard jingge. From this unexpected beginning, when the elderly Muslim woman Li Xiangrong recalled a chant known as kuhua (Grieving Song), women together with researchers have begun to collect chants, sometimes mere fragments, which were once the staple of women’s mosques. Li Xiangrong, from the famous Wangjia Hutong Women’s Mosque in Kaifeng, has stirred rememberings in others of her generation, and the elderly women have begun to teach kuhua to young girls and have started to talk of what life was like for earlier generations of women, particularly the years before the 1949 Communist government, when jingge were at their height of popularity.

Although the Communist government curtailed religious activity for many years, some Chinese Muslim women feel other aspects of Communist doctrine are what have allowed women to retain their roles as religious leaders. In an interview with the Women’s UN Report Network, Wu Yulian explained:

The Chinese Communist Party liberated us from the kitchen and it gave us the same duties and obligations as men. I believe that men and women are equal by nature and that the practice of restricting women in some parts of the Middle East, like not allowing them outside, not allowing them to drive or be seen by men is really unfair and excessive.

Yao Baoxia, an ahong at Wangjia Hutong, echoed this sentiment in an interview with NPR: ”The status is the same. Men and women are equal here, maybe because we are a socialist country.”

However, as the Women’s UN Report Network notes, the Hui community’s growing interaction with the rest of the Islamic world may invite controversy over the nüsi. When WUNRN asked Zhao Hongmei, a student at Yinchuan’s Institute for the Study of Islam and the Koran, if she would like to become an ahong, she bluntly replied, “Women aren’t allowed to be ahong.” Similarly, Guo Baoguang, of the Islamic Association of Kaifeng, told NPR that he has received complaints over including ahong in religious education forums. “There were some criticisms that women ought to be in the home, and ought not take part in social activities.”

But it’s possible that the increased dialogue could have the opposite effect. As Guo points out, China’s rising economic power comes with political and social clout. “The developments Chinese Islam has made, like the role played by Chinese women, will be more accepted by Muslims elsewhere in the world,” she says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook