Amazon Tribes Want to Remain Isolated–So They’re Getting the Internet

Project coordinator João Carlos Nunes Batista shows Ululupuene villagers how you can access the internet. (Photo: © 2015 Amazon Conservation Team)

For three days in August, Waura villagers in Ulupuene, a tiny settlement in the Xingu Park in Monto Grosso Brazil, celebrated late into the night. They hauled in fish from the Batavia river, seasoning them with “Indian Salt”—a tangy mix of peppers and salt they extract by roasting water hyacinths—and feasted on watermelons, squash and fresh Colombian coffee. Under the coconut trees and moonlight, people played music and danced.

The Waura, who are one of 14 tribes who live on the Xingu reserve, and one of 40 ethnic groups within the larger Xingu River basin, weren’t celebrating a rite of passage, nor one of the many mammals they revere as sacred kin. They were honoring something much newer: the arrival of the internet.

Now, after traveling 18 hours by truck and canoe, a large satellite dish and two silver laptops sat humming inside a pair of thatched ocas that looked 500 years old, even though they too were newly installed. Transmitting yet tranquil, the combined presence of thatch and wires seemed full of potential, but not without some risks.

A satellite dish that travelled for 18 hours by truck and canoe. (Photo: © 2015 Amazon Conservation Team)

For indigenous tribes of the Amazon, contact has too often spelled disaster. Since their earliest encounters with Europeans, more than a hundred years ago, the Waura have survived epidemics of measles and flus, been shot at by poachers, lost land and cultural heritage, and faced increasing pressure from soy farms, powerful soy lobbies, hydroelectric projects, and their own government. Despite these mounting pressures, the Waura have held onto their traditions, and kept many of them alive. Fish from the Batavia river is still their primary food source. Ceramics and wrestling matches continue to be central cultural practices.

And yet the Waura want the world wide web. They were, in fact, the ones who sought it out in the first place, approaching a conservation group to help them install and pay for it. Even though they know the web may bring unwanted visitors, less control over cultural property, or knowledge they find distasteful, they also know it comes with opportunity.

In a moment when Brazil’s soy lobbies are stronger than ever, and the Belo Monte dam, a major hydroelectric project, may soon threaten the river that feeds them, the villagers are hopeful that tools like Facebook and GPS technology may help them protect their land, and raise awareness about poaching and threats to their cultural heritage. They’re hopeful that this time around, contact may be a good thing.

Empowering indigenous villages through the internet has been part of official Brazilian policy since 2007, when the government announced a plan to provide free internet to native Indian tribes, by bringing satellite access to 150 isolated regions. “It’s a way to open communications between indigenous communities, former slave villages, coconut crackers, river fishermen and the rest of society,” former environmental minister Marina Silva said at the time, after signing the agreement.

Map of the Amazon Basin with the Xingu River highlighted. (Photo: Kmusser/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

For conservation groups, it’s also been a way to put the environmental management of the country in the hands of the people who know its forests and rivers best. Amazon Conservation Team, the non-profit organization that helped wire Ulupuene, has been training interested tribes how to use GPS technology, camera traps and ground information collection techniques for more than a decade. With the tools and skills to map their land and share their ancestral forest management practices, the hope is that tribes will be able to monitor trees on the ground and respond to illegal activities with greater force and precision.

So far ACT’s approach, which is animated by the idea that if forests die, local culture does too, has seen success. During their flagship project in Suriname, where a casino-style gold rush had devastating environmental impacts, they partnered with the Trio tribe to help them map their territories and track illegal mining. In one notable instance, the tribe was able to use GPS to identify where miners were illegally cutting portages through the forest, and stashing their canoes behind waterfalls to cover their tracks.

“By tromping through the forest with the GPS in hand, they’ve been able to track, and in some cases, stop, illegal mining activity,” says Mark Plotkin, founder of ACT, renowned ethnobotanist, and author of the best-selling book, Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice.“It’s an example of how good, old-fashioned elbow grease, and on-the-ground truthing with GPS technology, helped them figure out where the bad guys were getting in and put a stop to it.” Since then, ACT has worked with 30 other tribes in South America.

Deforestation in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil, where the Zingu National Park is located. (Photo: Pedro Biondi/ABr/WikiCommons CC BY 3.0 BR)

And yet, Plotkin says, you can’t just drop an iPhone from a plane and expect it to make a difference. Government efforts to wire these villages has been criticized for poor implementation, lack of training, and conflicting interests (the governor of Mato Grosso, the state where Xingu is located, is also one of the largest soy farmers in Brazil). The same is true for nonprofits and volunteers, many of whom come, build a solar project, or set up a router, and leave.

Without long term management, solar panels fall and scatter in the mud. Without training, a viable signal, or a desire to have them at all, brand new computers don’t get turned on.

It’s something that Plotkin and his wife, Liliana Madrigal, who oversaw the project in Ulupuene, have seen again and again. Not having a long-term, on-the-ground strategy is like doing “conservation from the air.” They say it can end up reinforcing a vicious narrative: that the natives don’t get it, or care.

“I go back to when Columbus first landed in the Bahamas, and took out his sword in the name of Ferdinand and Isabella,” Plotkin says. “The local chief, having never seen steel, reached up and grabbed the blade. And he bled. What I draw from this is that sometimes technology is good, sometimes technology is bad, and sometimes it’s both.”

For the Waura, getting internet has been the culmination of a years-long process that began in 2011, when their chief approached the Amazon Conservation Team and asked them to help rebuild their ancestral village on a southwestern portion of Xingu that they consider their spiritual home. Abandoned long ago, the original village was gone, and much of the surrounding land has been taken over by soy farms and ranchers, including a series of caves that the tribe considers sacred.

Once a place where their ancestors painted, and held piercing ceremonies for boys, the caves are now on a private soy farm, while portions of the once lush Xingu basin have denuded into dust bowls. The Waura hope that by reclaiming this land, they can help protect it, even rejuvenate it, while reviving their cultural traditions and establishing a stronger presence in the area.

Installing the satellite. (Photo: © 2015 Amazon Conservation Team)

With help from the indigenous association of Ulupuene and the local non-profit SynBio, ACT provided tarps, transportation, food, and whatever else the villagers needed—other than the manpower and raw materials; the Waura supplied those themselves— to rebuild their traditional ocas. But on the first go-round, they built the new village too close to the river and one night it flooded, inundating the huts with water, snakes, and frogs. So the villagers took down the ocas, moved them away from the river, and rebuilt them all over again.

The gardens came next. To supplement their diet of cassava and fish, and give their village some shade, they planted coconut trees, bushy pineapple plants, and rows of squash and watermelons. The children love it, as do the tapirs, an endangered pig-like mammal, who come mostly for the pineapples.

The push to wire the growing village—now home to 75 adults and at least a hundred children—began with a basic necessity: better contact with their indigenous coordinator, who lives in Brasilia—a 25 hour journey that involves a truck, a canoe, and a plane.

The initial idea was to build a radio tower, some 60 meters high, but that was eventually scrapped in favor of installing a more powerful satellite. In a series of actions that illustrate just how slow development can be, the dish had to be deconstructed by hand in the town of Canarana, where it was loaded onto the back of a pick-up, hauled 18 hours overland to the banks of the Batavia, where it was loaded into a canoe, and paddled an hour and a half down river to Ulupuene.

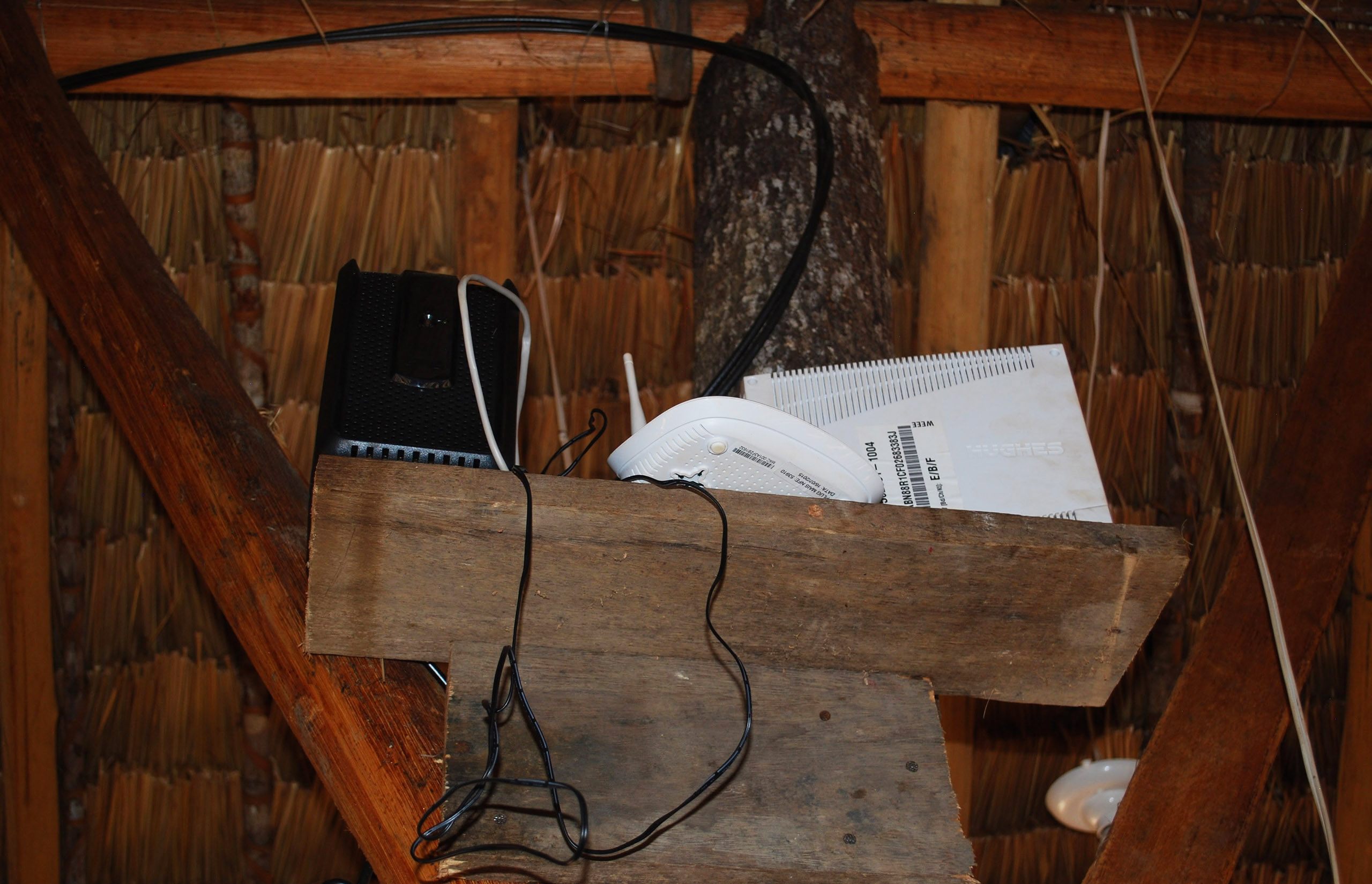

The router in situ inside a thatched oca. (Photo: © 2015 Amazon Conservation Team)

Now that the web has arrived, reception is spotty and costs are far from free. The signal works only three hours a day, usually at night, and the fees amount to nearly $300 a month, a bill that ACT pays. The computers are a major source of excitement–“it’s like candy for them,” Madrigal says, “like anyone else, they’re so excited to connect and share and post pictures of themselves”–but to make the most of it, the village has laid down guidelines: the internet is only to be used for emergencies, educational purposes, and initial wildlife monitoring.

Using Facebook, the tribe wants to post updates on poachers, share photos of their ceremonies, raise awareness about the power of the soy lobbies in their region, and combat the notion that indigenous land is idle, and therefore ripe for development. The tribe also plans on using camera traps to monitor local monkeys, which they eat during rituals. A couple of villagers have already created profiles, and are anxious to begin a cultural map–a project that would record their ancestral forest management practices, and store them in the cloud for future generations.

Madrigal is also hopeful that the web can help the Waura empower themselves against future threats as well, namely, the Belo Monte hydroelectric project, which is currently under construction, and has been widely criticized as a white elephant that won’t produce the energy that politicians and energy interests are promising.

For now, the satellite and computers are safely housed in Ulupuene’s ocas, away from any trees that could potentially fall in a storm. The children have been warned away from playing around the router. Even though the elders don’t use the internet much, they know its signal is precious.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook