Mapping Antwerp’s Last ‘Invisible Route’

One man tried to find a surveillance camera-free path through his city, and it wasn’t easy.

Late last year, Maarten Inghels of Antwerp, Belgium, was reading the paper when a news story caught his attention. Yet another camera system was about to be installed in the city, he read. Not only that, this particular system was smart, an active rather than passive watcher. “[It said] they could track down a car in 15 minutes—recognize a license plate and track down that car,” Inghels says.

Inghels is an artist and a poet, and he likes to write and think about invisibility and disappearance. He is also, this year, the official City Poet of Antwerp, so he was looking for ways to integrate these interests with those of his community. He began wondering how far this new network’s capabilities stretched. Could the cameras, for instance, recognize individual pedestrians? Did they know where he went every time he left the house?

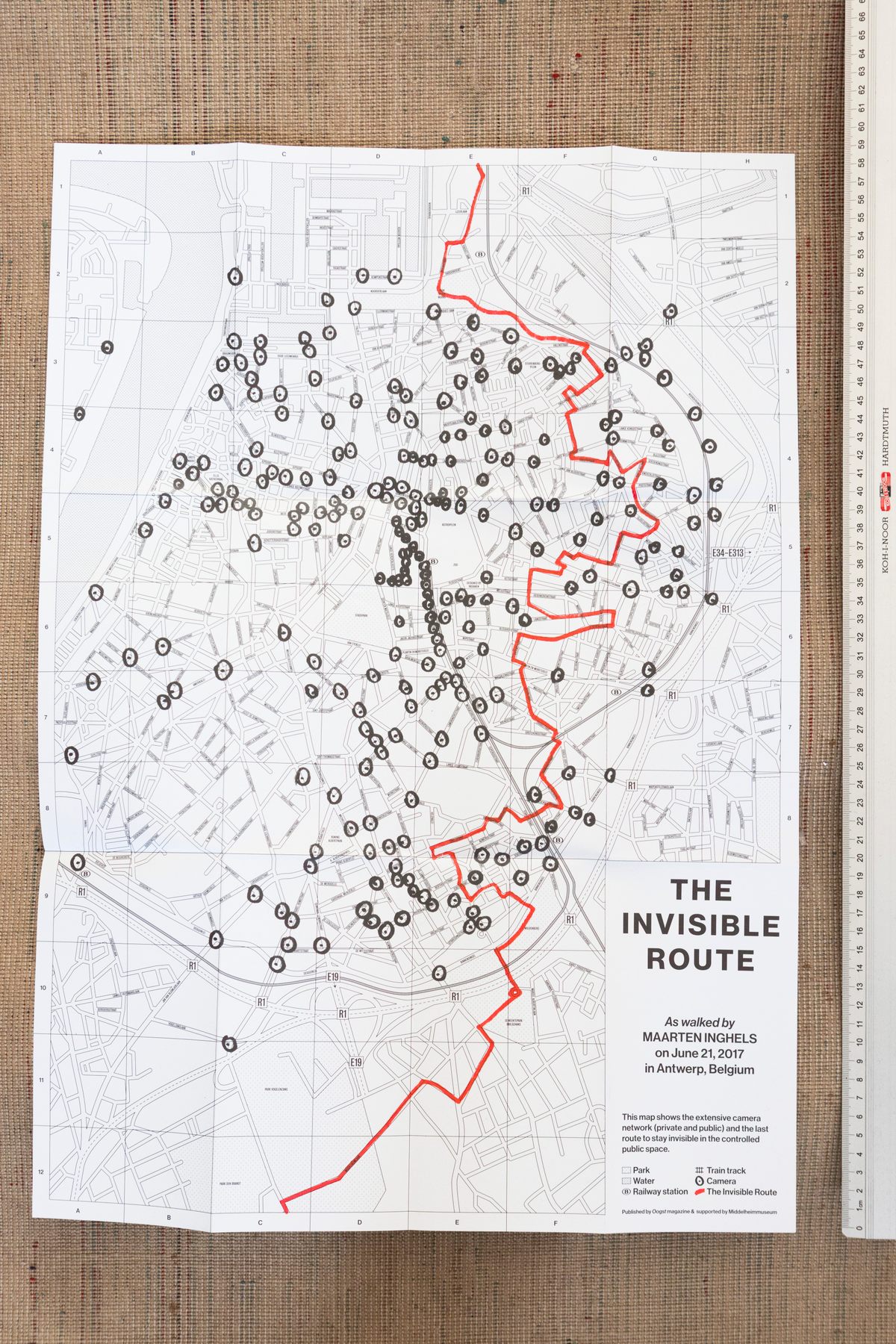

“That’s how I came up with the idea,” he says, “to find the last way to stay invisible in a public space in Antwerp.” Inghels set out to map an entirely camera-free path, which he eventually named “The Invisible Route.”

In modern urban life, surveillance is essentially a given. Although worldwide figures are difficult to ascertain, the most CCTV-heavy cities, including Beijing, London, and New York, have thousands or even tens of thousands of active cameras trained on public spaces. (As of 2013, Britain had about one camera for every 14 people.) Proponents of the systems argue that ever-watchful mechanical eyes help law enforcement catch perpetrators, and serve as a crime deterrent. Skeptics counter that blanket video surveillance doesn’t actually achieve these aims, and that such systems are ripe for abuse. As these arguments get hashed out, though, more and more cameras keep popping up.

Antwerp is no exception. Over the last few years, Inghels says, the number of cameras in his city has tripled. It’s now over 300, and that’s not counting the home security systems, storefront CCTV rigs, and other private cameras that are proliferating at the same time, without government involvement. (Inghels is himself intimately familiar with this upswing: “I have two cameras pointed at my house,” he says.)

For his mapping project, Inghels used a combination of internet research and good old-fashioned grunt work. First, he found a list of camera placements on the Antwerp Police website, and used that to narrow the routes down to a few possibilities. Then, last December, he hit the pavement. “I decided to walk them individually, to see if there was a shop camera, or a privately owned camera,” he says. Often, he’d be well on his way, feeling hopeful, and then find himself staring down the barrel of a lens, a feeling he describes as “disappointing.” It took him months to find a route that worked.

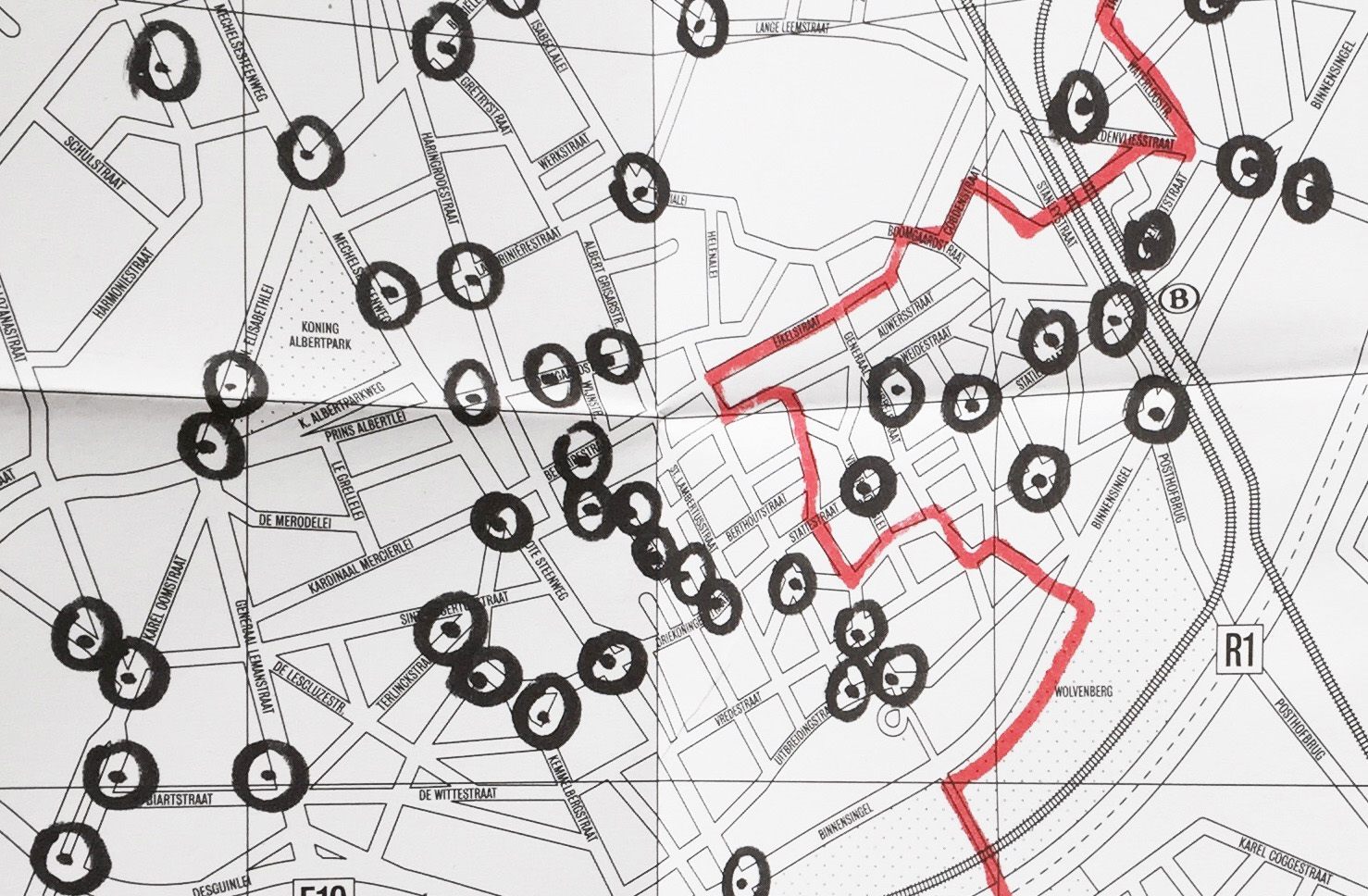

In June of 2017, he finally did. Antwerp’s Invisible Route starts on the southeast side of the city, near the modern art museum. It heads north, cuts through a small park, and crosses a railroad track. It then sneaks into the city proper, where it begins doubling back, dodging cameras left and right. (Inghels has drawn individual cameras as black circles with dots in them, so that the whole map looks alive with cartoon eyes.) It ends about six miles after it began, up on the city’s northeast side.

Inghels, who has lived in Antwerp for 10 years, says that plotting the route taught him new things about his city. “I discovered some hidden, small passageways—routes only for pedestrians,” he says. “I really like them. They’re like back doors of the city.”

He’s not necessarily against the cameras. “I can see the useful opportunities there,” Inghels says. Instead, the work is “more an ode, in honor of the art of disappearing.” While constructing the route, Inghels thought often of the poem “Crowds,” by Charles Baudelaire, in which the writer celebrates the unique, messy joy of wandering alone in a bustling city until you forget who you are, and the empathetic overload that results. “It is not given to every man to take a bath of multitude,” Baudelaire writes, but “…the man who loves to lose himself in a crowd enjoys feverish delights.”

In another work, “The Painter of Modern Life,” Baudelaire adds that “the passionate spectator” prefers “to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world.” Now, Inghels explains, would-be multitude-bathers can’t even take that first step of embracing anonymity. “That’s something that doesn’t exist anymore,” Inghels says, “because of the cameras.”

This poetic dimension also influenced the project’s form. Other contemporary camera map projects aim to stay up-to-date, so that people may avoid cameras or seek them out to feel safe (or to do performance art), or simply to keep people aware of their presence.

By contrast, Inghels’s map—which was also published as an insert in Issue 11 of Oogst Magazine—exists only in static form, as a piece of paper that reflects one moment in time. “It’s a naive exercise,” he explains. “It’s about a time and a world that doesn’t exist anymore… a world where you can be unseen.” The map, he emphasizes, is dated June 21, 2017: the last day he walked the route, and thus the last day he can be sure it was entirely invisible. It’s less a tool than an artifact, a vestige of something almost gone.

Indeed, the world is changing so fast, Inghels warns, that if you try to use the Invisible Route for its most literal purpose, it will almost certainly fail you. “Over the summer, the government has installed new cameras,” he says. “So it’s already out of date.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook