Behold Rahu, the Beheaded Asura, and Other Eclipse Monsters of Yore

From cosmic serpents to demon warriors, these creatures have been blamed for messing with the Sun and Moon.

Armed with a little science, modern humans can relish in the celestial mechanics of an eclipse without fearing the end times—but it wasn’t always that way.

Before we recognized the moon’s potential to block out the sun and vanish into Earth’s shadow, we sought answers from the gods. Without a full understanding of planetary motion and celestial alignment, we attributed the disruption of solar and lunar cycles to cosmic monsters.

While it’s tempting to interpret such tales as purely explanatory, the relationship between natural phenomena and myth isn’t always so clear. We often don’t know to what extent ancient cultures created stories to explain eclipses or saw their existing myths reflected in the movements of sun and moon. Certainly, generations of tradition allowed mythology to evolve and fulfill various cultural purposes.

Global eclipse mythology features a rogues’ gallery of moon thieves and moon-hungry behemoths. Meet a few of them now, and remember their audacity when you gaze up at the eclipse on April 8.

Apep the Moon Serpent

Ancient Egypt

Many solar eclipse myths revolve around the duality of light and darkness, good and evil. As you might imagine, that puts a rather nefarious spin on the sudden obstruction of the midday sun. Thus, Ancient Egyptian cosmology gives us Apep, the cosmic world serpent.

Apep (or Apophis) embodies chaos and death, making the monster a natural adversary for the sun god Ra. The serpent pursues Ra as the sun god pulls the burning sundisc across the sky, lighting the world. Every so often, Apep nearly consumes the sundisc, resulting in an eclipse. Luckily, Ra and the defenders aboard his sky barge always manage to fight free of the serpent’s shadowy coils.

Rahu the Beheaded Asura

Hinduism

Few eclipse myths can match the horror of Hinduism’s Rahu, one of the Asura, a kind of demon. Originally known as Svarbhānu, the wrathful demigod sought to live forever by drinking Amrita, the nectar of immortality. Lord Vishnu wouldn’t stand for this, however, and decapitated Svarbhānu before the liquid could pass down his throat. The decapitated head became the undying Rahu.

Divine comeuppance left Rahu with something of a chip on his shoulder—and also with no shoulders. Consumed by rage, he continually seeks revenge on the Sun and the Moon for informing Vishnu about his nectar theft. Rahu chases sun and moon across the heavens relentlessly—and occasionally catches them. But since Rahu is but a floating head, his victory is always temporary. After he swallows the sun or moon, either orb simply falls out of Rahu’s neck stump and continues its journey.

The Sebettu

Ancient Mesopotamia

The plague god Erra brought doom to Ancient Mesopotamia, and the Sebettu marched in his wake. The offspring of the sky deity An, these seven demon warriors spread sickness and death—and occasionally gathered in the sky to blot out the moon.

The epic Erra and Išum, written in the East Semitic language of Akkadian sometime around the eighth century B.C., describes the seven warriors as so deadly that their “breath of life is death.” It also relates that Erra mainly likes to let them loose on earth “when the clamor of human habitations becomes noisome.”

The Sebettu might seem like rather casual eclipse monsters, but their moon-blotting ways may have served a royal purpose. The Assyrians saw eclipses as dire omens, and particular lunar eclipses amounted to divine condemnation of the king. At times, this required the ritual death of a substitute king or šar puhi, who perished in the king’s place. Historian John Z. Wee speculates that the Sebettu may have functioned as a way of absolving the moon-associated king from guilt. Why stage an elaborate sacrifice when you can simply tweak religion to cast yourself as a victim of intermittent demons?

|

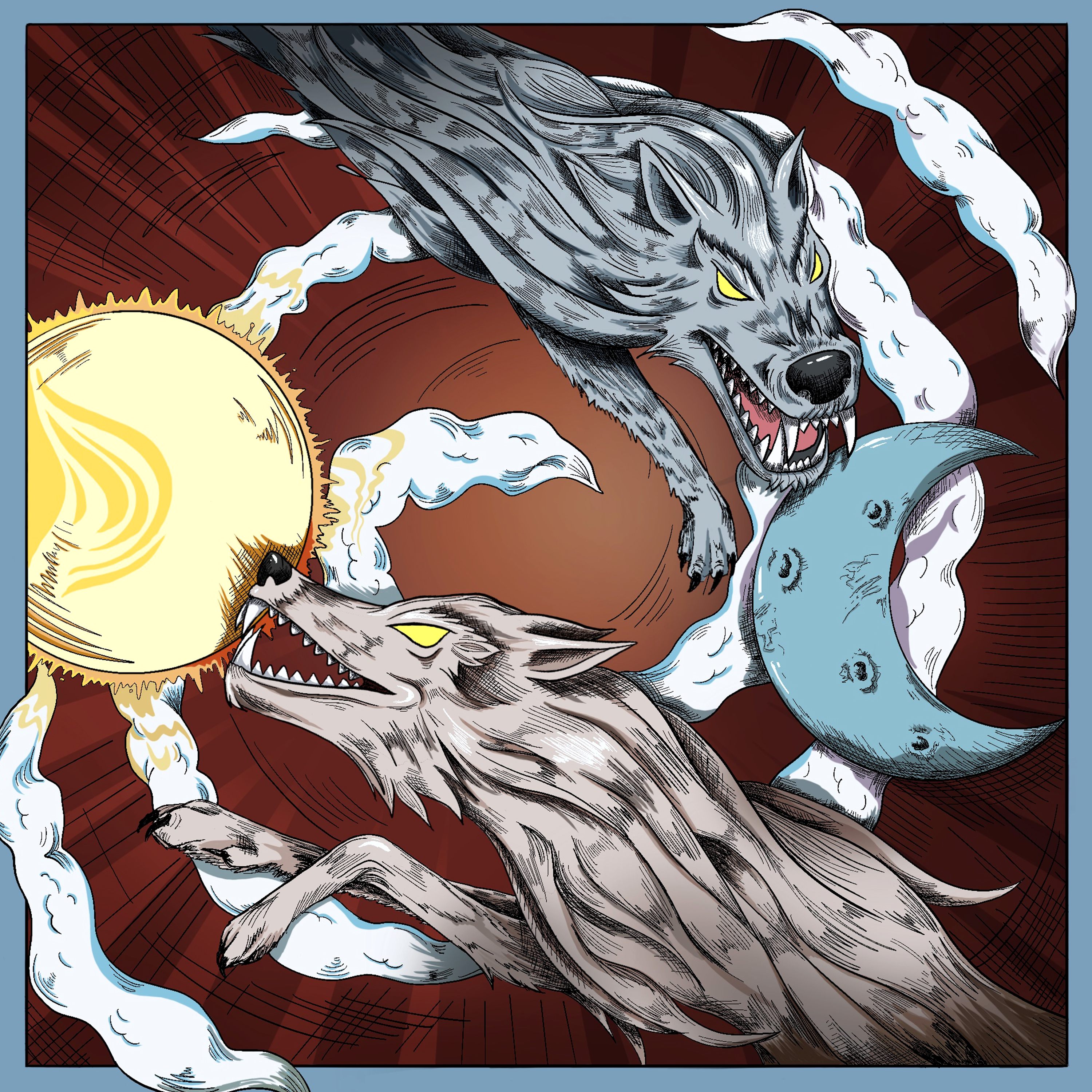

Sköll and Hati

Norse Mythology

When something dreadful happens in Norse mythology, you can safely assume Loki had something to do with it. The trickster god managed to father the ultimate world-consuming serpent, the queen of the underworld and a god-slaying giant wolf. That wolf, Fenrir, spawned the eventual doom of both sun and moon in the lupine duo Sköll and Hati. Yes, everything Loki touches turns to Ragnarök.

Sköll doesn’t get to gobble up the sun ‘til the end times arrive—and when he finally sinks his teeth in, the light of the world extinguishes in his grim belly. Meanwhile, Hati eats the moon. Stephen Hawking described the wolves as eclipse monsters in The Grand Design and many other publications follow suit, but not everyone’s convinced. Some commentators, such as skeptic Eve Siebert, argue that the often-cited Old Norse poem Grímnismál merely points to a dark eventuality and not recurrent events. Still, it’s possible the Norse saw these tales of doom reflected in eclipses, or even considered them near misses in an eternal race between light and all-consuming dark.

The Peri

Ancient Persia

Even sun-blotting monsters aren’t above redemption—and the Peri of Ancient Persia prove that sufficient cultural change can erase all cosmic wrongs.

Back in the 6th century B.C., the Peri were small, winged humanoids in pre-Zoroastrian Persian traditions. Like other “fairy” folk in global myth, their relationship with humans ranged from casual benevolence to mischievous destruction. According to folk historian Carol Rose, they might help you out of a tough spot, ruin your crops, or darken the sun.

The Peri continued in this role for more than a millennium, until Islamic culture rewrote them as repentant fallen angels. Later tales described their penance as complete and by the end of the first millennium, they even appear in the epic poem Shahnameh as loyal servants to earthly kings.

This piece was originally published in 2017 and has been updated as part of Atlas Obscura’s Countdown to the Eclipse, a collection of new stories and curated classics that celebrate the 2024 total solar eclipse and the Ecliptic Festival in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook