How Did The Hugest Whales End Up With Baleen Instead Of Teeth?

The answer is: they literally sucked.

In the middle of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin took a moment to note down one of the natural mysteries that dogged him most. ”The Greenland whale is one of the most wonderful animals in the world,” he wrote, “and the baleen, or whalebone, one of its greatest peculiarities.” He goes on to wonder, on paper, why in the world this strange structure ended up the way it did. Why do whales have these huge rows of hairy protrusions, rather than some more common eating apparatus, like teeth or a beak?

Thanks to new research from the Museums Victoria and Monash University—and a 25 million year old fossil whale named Alfred, dug up in in Washington State—we’re now slightly closer to an answer.

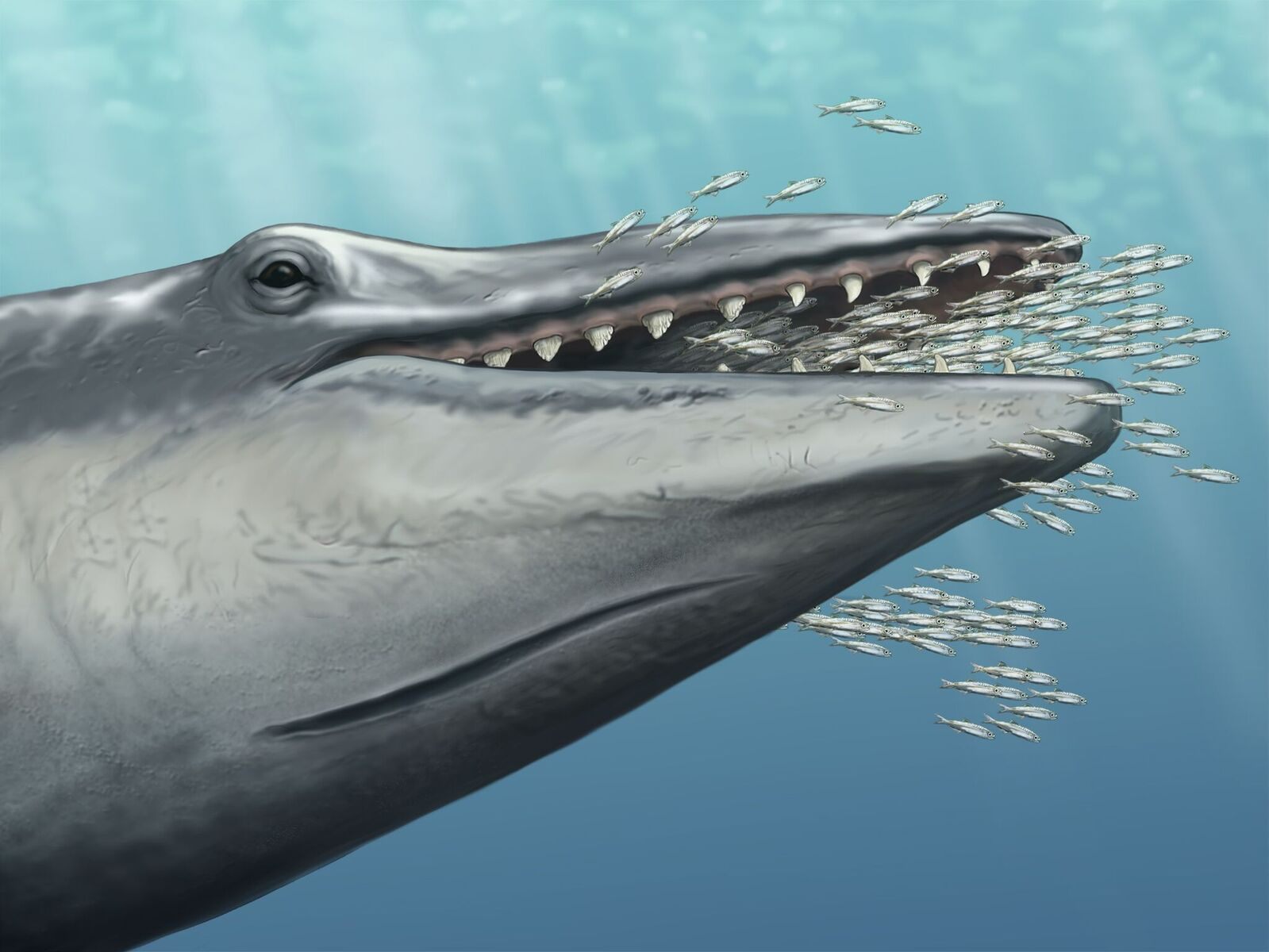

The researchers, led by Dr. Felix G. March, published their findings earlier this week. In the past, they explain, all whales had sharp, spiky teeth. They used them like your average predator, to tear their food apart. But although toothed whales, like sperms and orcas, stuck to this strategy, other contemporary species, like blues and humpbacks, now feed using baleen, which trap enormous amounts of plankton and other tiny creatures while filtering seawater out.

That means that at some point, an in-mouth switch occurred. For a while, researchers thought that whales probably evolved baleen while they still had teeth, and that the former slowly overtook the latter.

But Alfred—who is an aetiocetid, an indirect ancestor of today’s baleen whales—suggests a different path. When scientists examined his fossilized teeth, they found they were covered in tiny horizontal scratches. This is evidence that Alfred probably fed via suction—using his tongue to slurp in prey, along with some scratchier bycatch like sand and small rocks. (Some animals, like walruses, still feed this way, and have similar tooth grooves as a result.)

Over time, as whales perfected this suction strategy, it became less and less advantageous for them have teeth at all. Eventually, the teeth disappeared. Only then did baleen crop up to replace them, the researchers postulate. And as a result, the whales literally stopped sucking.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook