Libraries And Cities Are Terrible At Keeping Track of Art

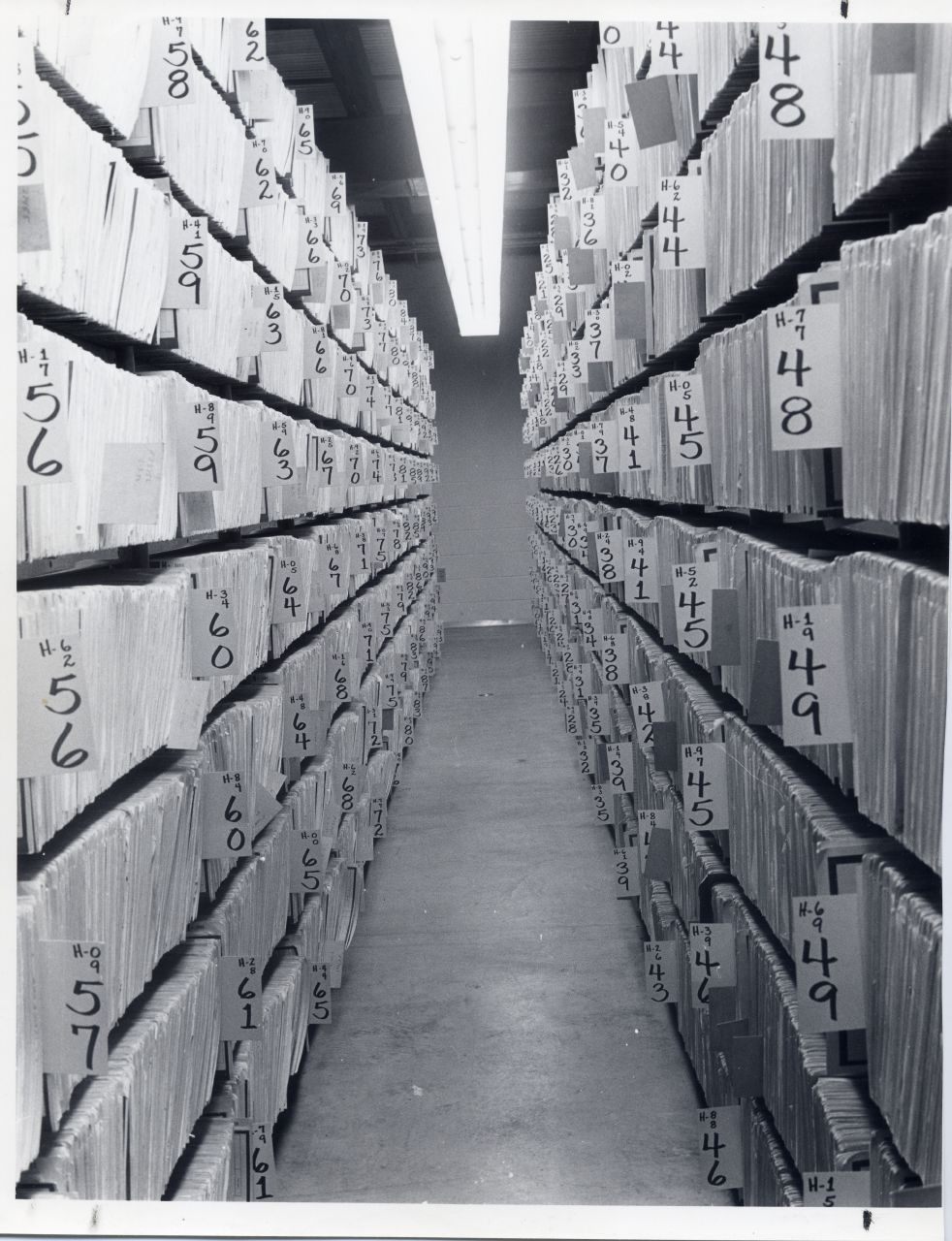

The inside of a library’s catalog.(Image: Texas State Library/Flickr)

Late in May, when the Boston Public Library was still missing a Rembrandt etching worth $30,000 and a 16th century Dürer print worth $600,000, the situation looked bad. More than a dozen staff members were searching through tens of thousands of prints and drawings, without any luck, and the local press was reporting on a recent audit that had scorched the library for its less-than-stellar inventory management. “It is critical that the BPL have an inventory report that should list each item it owns,” the auditors wrote. “This consolidated inventory list does not exist.”

Then, last week, just one day after the library’s president announced her resignation, the two prints turned up—just 80 feet from where they were supposed to be.

In Boston, the value of the prints that went missing was high, and as a result, the reaction—press coverage, police involvement—and the consequences were severe. But the problems identified in Boston are far from unique to this one library.

Across the country, in city art collections and special collections of public libraries, one-of-a-kind items are routinely misfiled, misplaced, lost or stolen. And sometimes, routine mistakes and slipshod documentation grow into a much more intractable problem, with large portions of public collections being managed by institutions who have no idea what’s in them and no full inventory of their holdings.

For instance, a library in Paterson, New Jersey, lost 20 pieces of antique furniture and bronzes and waited six years to report the loss to police. An Indiana library couldn’t find four paintings by the German artist Julius Moessel and never even tried to collect the insurance. An audit in Long Beach, California, found that about an eighth of the city-owned art collection could not be accounted for. The New York Public Library is missing a handful of maps dating back to the 15th and 16th centuries—and didn’t even notice it had lost one of Ben Franklin’s workbooks, until the person who inherited it offered to sell it back to the library. (The NYPL is currently suing for possession.) The Chicago Public Library has lost the vast majority of the 8,000 books, some of them now rare and valuable, that were donated to the city in 1871 and made up the library’s original collection. In 2011, the San Francisco Civic Art Collection wasn’t even sure how many pieces were in its collection. How did this problem first come to light? Well, some of its valuable pieces were found basically just lying around in a dank, watery hospital basement.

These problems aren’t restricted to a city level, either. At the Library of Congress, the inspector general noted in a recent report that “there is no comprehensive inventory or condition statement which covers the Library’s collections.” An examination of six presidential libraries found that the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library had inventory information for only 20,000 of its 100,000 items. When the Smithsonian Institution’s Office of the Inspector General examined the National Museum of American History’s inventory practices in 2011, the inspectors could not find 10 percent of the objects in their sample: The museum, the OIG reported, was missing ancient Greek and Arabic coins, gold watches and military medals, original works of art and parts of George Washington’s bed. (In the past few years, though, a museum spokesperson says, “All of the issues in the report have been addressed to the satisfaction of the auditors.”)

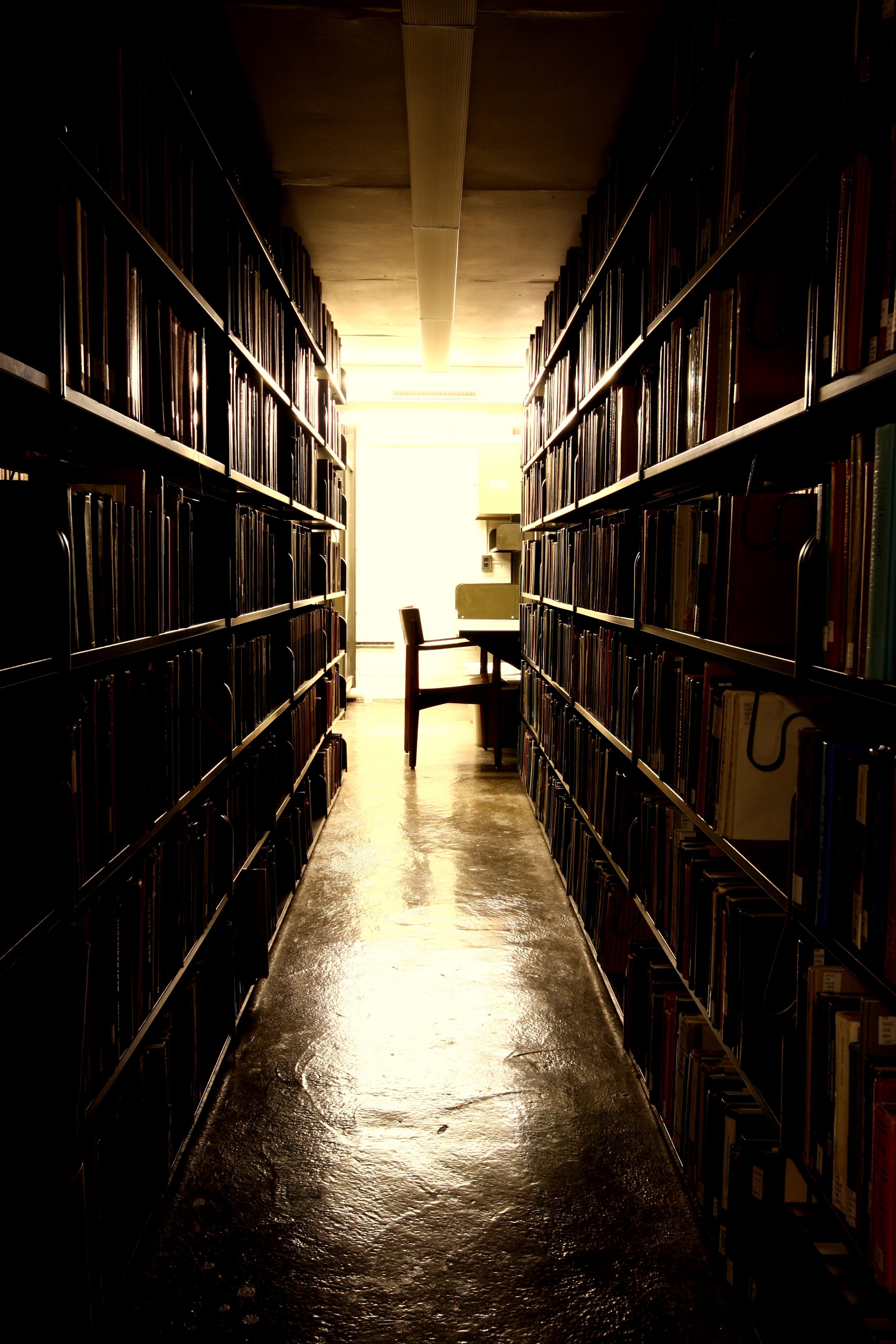

The British Library (Photo: Luke McKernan/Flickr)

To some extent, missing and mislaid items are a hazard of gathering so many objects in one place—many public collections are so large that it’s impossible to keep an up-to-date inventory of every single item. “These collections are vast,” says Kara M. McClurken, who heads preservation services at University of Virginia Library. “If you’re talking about a couple hundred items, it’s easy to go through once a year and make sure everything’s there. But when you’re talking about millions of items…if it took you 2 minutes to inventory each time, a full inventory can take years.”

Well-managed collections routinely inventory parts of their collection every year: the best practice, according to the Association of College and Research Libraries’ guidelines, is to conduct inventories, routinely, but on a random parts of the collection. But that’s a safeguard, not a fail-safe. An item could be inventoried and misfiled the next day. Ultimately, McClurken says, “There’s no way to be sure, at the end of every day, that everything is where it ought to be.”

For large public libraries like BPL, art can be a particular challenge. “Librarians are trained to catalogue books and CDs. Art is an outlier,” says Camille Ann Brewer, the executive director of University of Chicago’ Black Metropolis Research Consortium. who has studied urban public libraries’ management of art collections. “With cutbacks, librarians are asked to do more with less, and artwork gets put on the back burner.”

In her study, Brewer found that “urban public libraries…generally are not employing industry best practices for handling museum-quality fine art objects.” As a rule, she says, librarians don’t have much formal training in how to catalogue art, and those sort of holdings end up outside the main library catalogue.

On a basic level, special and art collections resist easy organization. A library’s regular stacks contain books, which are generally the same size and the same shape and, if need be, can be replaced. Books can be physically labeled, too. But for a work of art or a rare book, a physical label might obscure some important detail. Many libraries label rare books with book flags—but that doesn’t fly for prints, paintings and statues.

Uris Library (Photo: Alex/Flickr)

Collections might also choose to organize strangely shaped objects in different ways. One institution might group an entire collection in one area, while another might keep flat objects in one place, strangely shaped small items in another, and large objects somewhere else entirely. Those practices might change over time, so that one part of the collection is organized according to an old schema and another according to a newer paradigm.

All this adds up to the reality that unique items won’t always find their way back to their proper spot: “When it’s more complicated and less standardized, there’s going to be a greater margin for error,” says McClurken. Even the ACRL guidelines recognize that following best practices won’t keep items from being mislaid.

The bigger problem is when best practices fall away and these problems accumulate, until large collections are left uninventoried and unknown. Libraries and cities, after all, are not art museums. Their main purpose is to not to collect, store and take care of valuable pieces of art (or even rare books.) In the case of civic art collections, often the scope of the collection exceeds the budget for its care, a persistent issue in San Francisco.

Even a well-managed library collection can resist legibility—a librarian can always be surprised by some amazing text or object hidden among the stacks. But if libraries have not even completed one inventory of their most valuable objects or do not have the resources to conduct regular, random spot-checks, the problem becomes larger than just a few mislaid objects. The public institutions entrusted with some of the country’s most valuable and fascinating treasure end up becoming giant, only-sort-of-organized messes—the equivalent of the closet in your childhood home that hasn’t been organized or cleaned for years, even as your parents keep adding more to the pile. When there’s no system to help a person sort through that many objects, it’s no wonder that occasionally a $600,000 print might disappear.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook