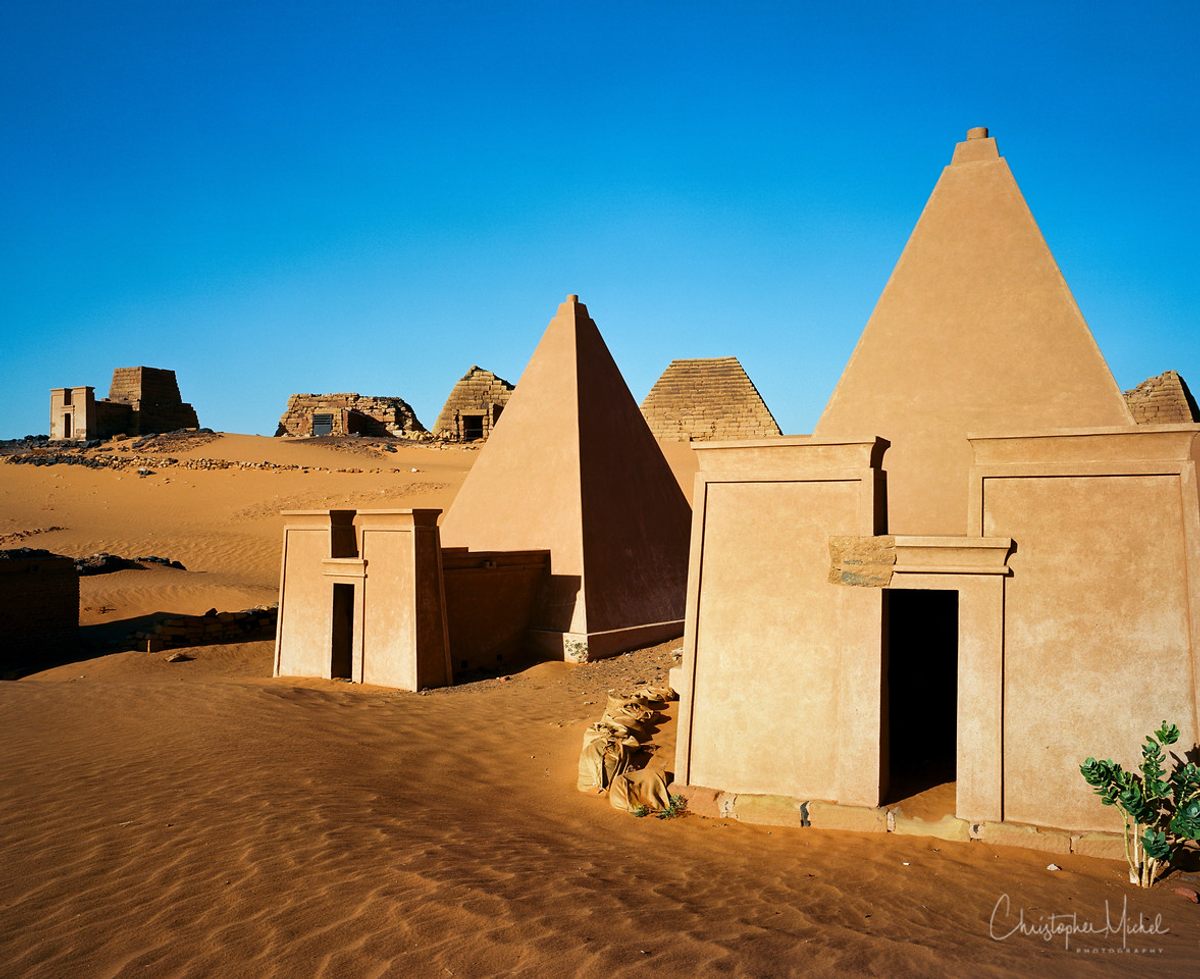

A New Look at the Little-Known Pyramids of Ancient Nubia

A photographer’s journey deep into the Sudanese desert.

In 2011, photographer Christopher Michel chanced upon an online course about ancient Egypt and signed up. What was intended to be a diversion led, some six years later, to a voyage of 8,509 miles, to the orange deserts of Sudan.

Although it’s less famous than the grouping of pyramids at Giza in Egypt, the complex at Meroë in Sudan is remarkable. More than 200 pyramids, primarily dating from 300 B.C. to A.D. 350, mark the tombs of royalty of the Kingdom of Kush, which ruled Nubia for centuries. They are recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, yet they remain relatively unknown. The Nubian pyramids differ from Egyptian ones: They are smaller—20 to 90 feet on a side, compared with the Great Pyramid’s 756 feet—with much steeper sides, and most were built two thousand years after those at Giza.

“When I thought of pyramids, I thought about the Great Pyramids of Giza,” says Michel. “I hadn’t known that Egypt had significantly influenced the Kushite Kingdoms of Nubia to the south—and that over 3,000 years, the Nubians would adopt aspects of Egyptian language, religion, and technology. While the ancient Egyptians basically abandoned pyramids for hidden tombs, the Nubians continued to use pyramids.”

For an archaeological site of such significance, Michel found Meroë to be remarkably tourist-free—no doubt due to the warnings about travel in Sudan. As a precaution, he bought a satellite phone and registered with the U.S. State Department. “It turned out to all be completely unnecessary,” he says. “The Sudanese people couldn’t have been kinder or more hospitable.”

Most of Michel’s time in Sudan was spent camping and visiting archaeological sites. “It was pretty rough going—blazing desert heat, blowing sand, and millions of very, very annoying gnats. But completely worth it,” he says. “Sunrises and sunsets over red, wind-sculpted sand dunes engulfing vast pyramid complexes. And almost no tourists. Just the occasional villagers or desert nomads living very traditional lives amidst ancient, yet advanced, artifacts of another time.”

Michel traveled with renowned Egyptologist Bob Brier, known as “Mr. Mummy,” for the experiment in which he mummified a modern human cadaver. Atlas Obscura chatted with Michel about his experience and the particular thrill of retracing the steps of ancient rulers.

What did it feel like to stand in such an ancient setting, surrounded by pyramids?

Honestly, it felt like I had been transported back 2,000 years. These ancient places haven’t been commercialized. It’s just you, desert, and history—and the occasional camel, who wander unbothered through the deserts.

Did Bob Brier tell you any unusual or surprising stories about Meroë?

Archaeologist, explorers, and treasure hunters have been digging around the Meroë complex for over a thousand years. Almost all the Nubian pyramids have been plundered by tomb raiders looking for treasure—sadly causing significant damage to these sites over the years. Bob shared the story of a treasure hunter and doctor, Giuseppe Ferlini, who blew up more than 40 tombs looking for valuables in the 1830s. At the time, no one thought it was a problem. Hard to believe.

You’ve photographed in some interesting and remote locations. What stood out to you about your experience in Sudan?

I have one very specific memory of visiting a deep desert well. Above the well was a wooden frame and rusted pulley—and there was a large nomadic family there collecting water. A young girl was leading two donkeys that pulled the bucket from the well. Twenty or so camels fought to drink the well water that was poured into a wooden trough. Nearby the pulley was a rusted, wrecked electric motor. In remote Sudan, the old ways are the ones that work. I imagine that the lives of these people may not be much different than those of their ancestors who watched those pyramids being built. In Sudan, the past is alive.

What precautions do you have to take with your equipment when you’re photographing in a desert, in the heat and the sand?

I brought two cameras—a Fuji X-Pro2 and a Mamiya 7II medium-format film camera. There was a dust storm almost every day. And that Sudanese sand is some of the finest, most invasive sand in the world. The trusty Mamiya delivered for the whole trip. But, although I kept my Fuji covered most of the time, the sand absolutely destroyed that camera. Badly enough that it just stopped working altogether, and was buried in Sudan. One day, some future archaeologist will find that camera and start looking for the bones of the photographer.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook