Newly-Released Satellite Images Show Shocking Destruction of Palmyra

Photos from space show ISIS damage that researchers had not expected.

Temple of Bel in Palmyra, which was destroyed in August 2015. (Photo: Bernard Gagnon/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Last May, the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra became the site of a number of tragedies after ISIS seized control. It was the backdrop of horrible human violence, a place of execution and other atrocities. Then, the terrorists took aim at the ruins itself, blowing up some of the remnants of centuries-old civilization.

More recently, though, Palmyra was retaken by the Syrian Army, backed by Russian forces, and as troops cleared the area of explosives, archaeologists watching from afar were eager to assess the damage to the ancient ruins.

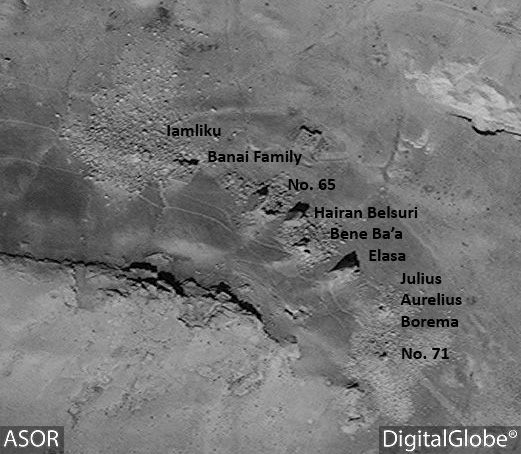

Contrary to the initial wave of reporting that indicated the wreckage wasn’t as bad as many feared, the news is not good. Satellite images obtained by DigitalGlobe on March 30 show previously unreported destruction in Palmyra—surprising because the regime has rarely stayed silent about their exploits.

In outlying areas of the ancient city, five more Roman-era tower tombs have been at least partly destroyed, according to an analysis of the images. And in the southeast necropolis, satellite images show fresh looting pits and a funerary temple that has been reduced to rubble. These monuments had been intact back in September, when DigitalGlobe released its last batch of Palmyra images.

No visible destruction of Tower Tombs in the Valley of the Tombs in June 2015. (Photo: ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives and DigitalGlobe)

“This area has been in a zone of silence for months,” said Allison Cuneo, project manager for the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) Cultural Heritage Initiatives.

Cuneo and her colleagues have been putting together extensive weekly reports, which are sometimes more than 100 pages long, summarizing the latest damage to cultural heritage in conflict-stricken Syria and Iraq. The researchers cull information from satellite data, news reports, social media, sources on the ground and sometimes even ISIS propaganda. Their initiative, which launched in August 2014, is in part funded by a grant from the U.S. State Department. That relationship allows Cuneo’s team access to DigitalGlobe images that would normally be very expensive to obtain.

September 2015: Visible damage to Tombs of Iamliku, the Banai Family, Julius Aurelius Bolma and Tomb No. 71 in the Valley of the Tombs. (Photo: ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives and DigitalGlobe)

Palmyra, a UNESCO world heritage site, had been on the ASOR initiative’s list of high-priority satellite targets. But the team has only been able to get a few glimpses of the ancient city, likely because of images of areas with heavy ongoing combat tend to be classified, Cuneo told Atlas Obscura.

The tower tombs at Palmyra were tall, multi-story buildings where the city’s rich families laid their dead to rest. The sandstone funerary monuments were used from around 50 to 300 A.D.—in the midst of Palmyra’s heyday, when the city was incorporated into the Roman empire and sat along an east-west trade route that connected the Mediterranean to Asia. While the latest satellite images showed damage to at least five tower tombs, another seven tower tombs showed signs of damage in the September 2015 images from DigitalGlobe.

“What’s strange is that there hasn’t been any propaganda related to these tower tombs at all,” Cuneo said. ISIS militants aren’t known for keeping quiet when they destroy monuments art objects they considers idolatrous under their hardline interpretation of Islamic law. At Palmyra, the group boasted its detonation of big monuments like the Arch of Triumph, the Temple of Bal and Baalshamin Temple over social media and in their magazine, Dabiq.

March 30th, 2016: Visible damage to tombs (from north to south) No. 65, Hairan Belsuri, Bene Ba’a, and Elasa in the Valley of the Tombs. (Photo: ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives and DigitalGlobe)

While it’s possible that the towers could have been damaged in combat, Cuneo said that the concentrated debris scatter in the satellite images has the signatures of intentional destruction.

Michael Danti, a Boston University archaeologist who has worked in Syria and Iraq and is also part of the ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives, wanted to emphasize that there was a lot of damage to Palmyra occurred before ISIS arrived.

“That might get lost in translation over time,” Danti said. “They were the primary culprit, but not the only culprit.” Danti has seen artifacts turn up on the antiquities market that he suspects were looted out of Palmyra before ISIS took the city, when the Syrian regime had militarized the archaeological site. He also noted that the medieval citadel overlooking Palmyra was damaged not by ISIS, but by airstrikes.

Part of the reason the ASOR team members are trying to document damage to Syria and Iraq’s cultural sites is so that they can act swiftly to help restoration efforts once the region is more secure. On Sunday, Irina Bokova, the Director-General of UNESCO, announced her plans to send an expert mission to Palmyra as soon as possible. And until then, it might be difficult to get a handle on the extent of the damage.

“Combat is incredibly destructive,” Cuneo said. “It has both visible and invisible negative consequences on really fragile ancient sites.” For example, airstrikes may have undermined the structural integrity of nearby ancient buildings; it’s also unclear how unexcavated archaeological material that still lies below the surface of Palmyra has been affected, she said.

And Palmyra is just one piece of the puzzle, Danti said, rattling off a list of all the other cities that are going to need rebuilding, including Mosul, Raqqa, Apamea, Dura Europos, Hatra, Aleppo, Homs, Nineveh and Nimrud.

“It’s really daunting,” said Danti. “Most of us could very easily spend the rest of our careers helping the Syrian and Iraqi people put it all back together.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook