Just About Everything We Know About the Pard

The mythical big cat was once believed to make up half of every leopard.

Some animal hybrids are common, like mules. Others are unusual, like zonkeys (that’s a zebra-donkey), or untameable, like wolfdogs, or not-entirely-healthy, like ligers. And some animals that were thought to be hybrids aren’t hybrids at all. Take the leopard, the offspring of a lion and a “pard.” We know now that leopards are, in fact, their own thing: the offspring of a mommy leopard and a daddy leopard. But for a long time, leopards were believed to be the sterile, degenerate spawn of a lioness and a male pard. The pard was a terrifying semi-mythological big cat with a lust for blood. But where did this puzzling creature emerge from?

One of the earliest known references to the pard comes from Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (the chapter is entitled “Lions; How They Are Produced”),which dates to around 77 A.D. There, he describes how the lascivious male pard seeks out seductive female lionesses on the banks of Africa’s rivers, where species mingle and mix, and hideous hybrids are born. “Hence arose the saying,” writes Pliny, “that ‘Africa is always producing something new’.” Later, the male lion, recognizing the “peculiar odor of the pard” on his lady lioness love, will “avenge himself with the greatest fury.” But by then it is too late, and the lioness is already pregnant with a leopard. It’s been suggested that Pliny may have believed that pards were male panthers, which are themselves, in Asia and Africa, black leopards.

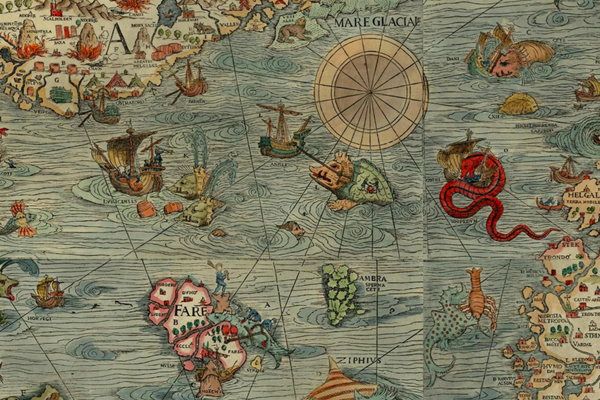

The authors and illustrators of medieval books of beasts embraced pards with gusto. These books are veritable menageries of pards—scowling, snarling, and generally making a nuisance of themselves. The authors struggle to draw these beasts, which they knew only from complicated, even contradictory, descriptions. What they usually have in common, however, is spots: In Isidore of Seville’s seventh-century Etymologies, pards are described as having a “mottled coat,” speckled with white like a giraffe’s. Swift and “headlong for blood,” they kill their prey with a single leap.

Six centuries later, in the 13th-century Bestiary, pards acquire a bloodthirsty, even demonic, reputation. “The mystic pard signifies either the devil, full of a diversity of vices, or the sinner, spotted with crimes and a variety of wrongdoings,” reads the caption beneath its snarling face. The Antichrist, it adds, is known to be a pard. In Revelations, the Antichrist is described as a beast “like unto a leopard,” with a bear’s feet, a lion’s mouth, and a dragon’s power. All of a sudden, the pard had become something far more than a simple panther straying from its taxonomic lane.

Pards appear in poetry, too. In As You Like It, Shakespeare says a soldier, “full of strange oaths,” is “bearded like the pard.” (This particular pard presumably inherited a mane from its leonine cousins.) Two centuries later, in 1819, Keats describes Bacchus, god of winemaking, fertility, and generally having a good time, as being “charioted” by “his pards.” To the American writer Joseph Holt Ingraham, in 1845, they were “velvet-footed” as they crept upon their prey.

What pards represent, however, is a long-standing general confusion as to how big cats—jaguar, cheetah, lion, leopard, panther (to say nothing of tigers, lynxes, or New World big cats, such as jaguars or mountain lions)—are related to one another, in the West at least. These far-off beasts were barely more imaginable than the Antichrist himself. In the 14th-century Byzantine poem, An Entertaining Tale of Quadrupeds—a dialogue between various animals—the terms “pards,” “cat-pards,” and “leopards” are all thrown around with relative abandon. The leopard is told he is a “beast that’s born in sin and brought up out of wedlock,” whose lioness mother has washed the scent of her pard lover from him. If the lion smells it, the writer suggests, he will kill her and never mate with a lioness again.

The poem gives still more clues about the natural history of the mysterious pard. They are apparently resistant to fleas (their pelts, therefore, make excellent bedspreads), they have comically short tails, and they live in quarries. These last two nuggets, Nick Nicholas, the Tale’s translator, observes, suggest a possible confusion with a lynx. Either way, the text is sufficiently ambiguous for one illustrator to draw a pard as a scraggly lion, and the next as a tamed cheetah wearing a collar.

After centuries of confusion, by the 1750s, biologists knew definitely that leopards are not a hybrid species. They appear in the 1758 edition of System Naturae, one of the first attempts to catalogue all animals, as creatures in their own right. “Pard” was still in their initial scientific name, Felis pardus, and appears twice in the one they go by now, Panthera pardus pardus.

Today more glamorous mythological beasts—think unicorn, sphinx, or dragon—dominate the fantasy limelight, and pards have virtually faded from memory. Where they appear in modern texts, it’s often in passages ripe with literary allusion. In Vladimir Nabokov’s 1969 novel Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle, handmaids pounce “like pards”—killing, presumably, with a single leap. But beyond that, they mostly remain caged in their medieval bestiaries, where their anxious, feline faces seem to say: “I really hope no one realizes I’m not actually real … ”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook