Preserving Ireland’s Ancient, Mysterious Tree-Based Alphabet

Across Ireland, hundreds of millennia-old Ogham stones are slowly weathering away.

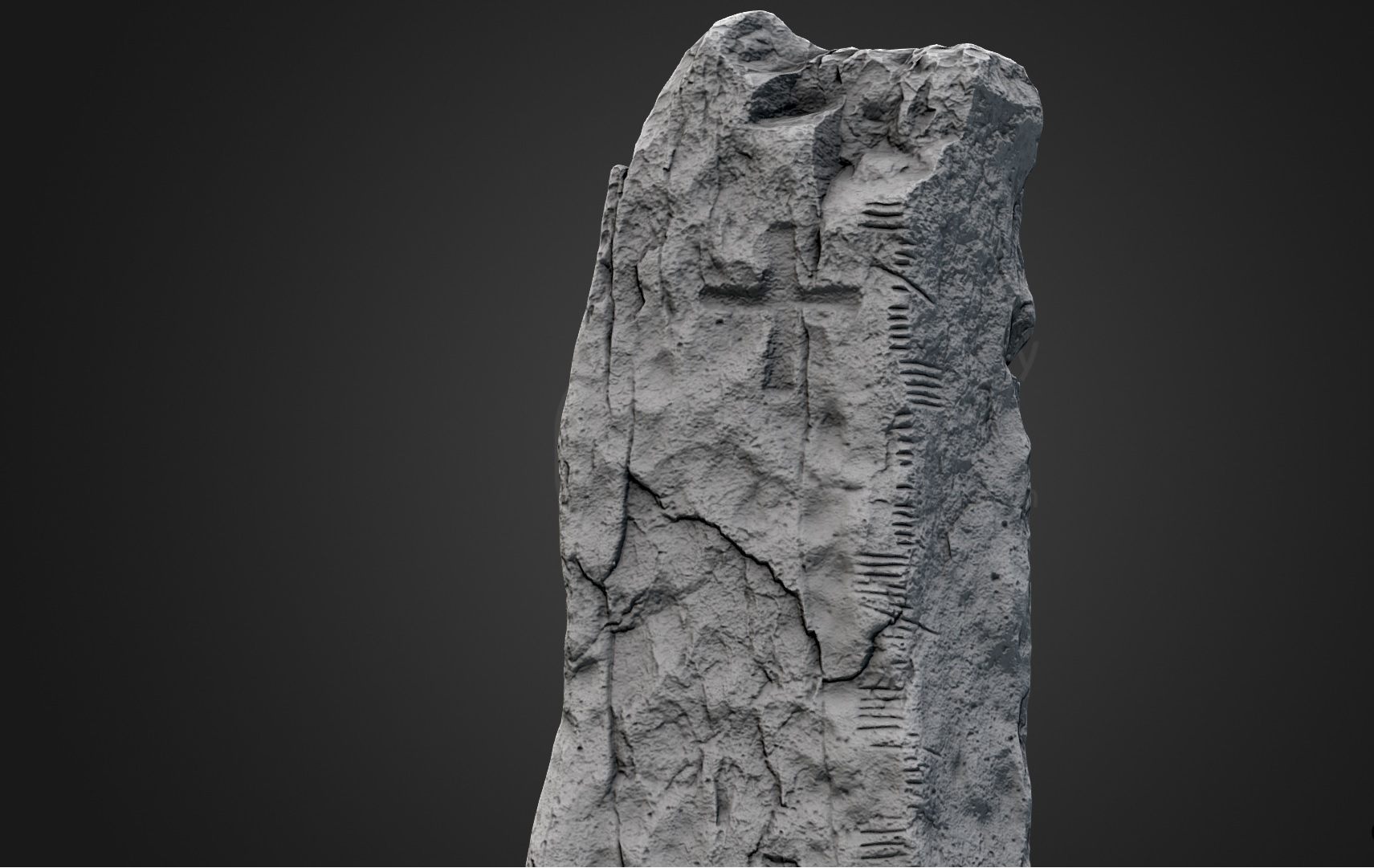

A 3-D scan of the Ballymorereagh Ogham stone. The inscription translates to “Cellach son of Mac-Áine.” (Photo: Nora White/Ogham in 3-D)

As an archaeological linguist working in Dublin, Nora White has spent her fair share of time digging through archives and poring over manuscripts. But when she wants a real taste of Irish history, she skips the library altogether. She heads to a hilltop or a secluded field, and she looks for a weathered old rock with slashes cut into the sides.

White studies Ogham—a mysterious Irish alphabet found on hundreds of scattered stones all over the country. Also called the “Celtic Tree Alphabet” due to its unusual letter scheme, Ogham dates back to at least the 4th century, when Gaelic speakers created it in order to translate the unique sounds of their language into written form. Today, they’re fonts of linguistic knowledge and scholarly mystery, and lightning rods for cross-millennial empathy. ”There is no doubt that you get a feeling of connection with the past,” says White. “You can’t help but wonder about the person commemorated and the one commissioned to carve the stone.”

There are about 400 known Ogham stones in the world—360 in Ireland, and the rest scattered between Wales, the Isle of Mann, and Scotland. Most are monuments or border markers, engraved with the evocative names and genealogies of their owners—”Belonging to the Three Sons of the Bald One,” or “He Who Was Born Of The Raven.” More are almost certainly lurking—hidden stones can (and do) pop up occasionally, built into churches, unearthed at construction sites, or hiding out disguised as decorative stonework.

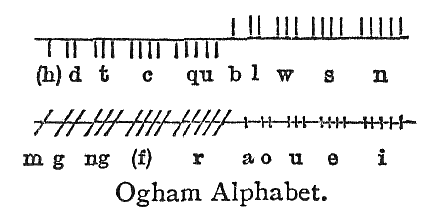

A key to the Ogham alphabet—on the sides of stones, the main “stem” is vertically oriented instead of horizontal. (Image: Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language/Public Domain)

On a purely linguistic level, Ogham isn’t too hard to master. Each of its 20 characters, or “trees,” is made out of a reference line, or “stem,” crossed by one or more slashes, or “twigs.” Depending on the number and direction of these twigs, the letter codes for a particular sound. To aid in memorization, each letter also has a name—often, though not always, a tree that starts with the sound the letter represents. The “B” sound, for example, has one twig sticking out on the right, and is called “Beithe,” or birch tree.

When scholars memorized the letters, they’d group them by twig direction, and count up by twig number. The right-sided twigs go “Beighe, Luis, Fern, Sail, Nin” (“birch, herb, alder, willow, letters”). The horizontal slash-throughs go “Ailm, Onn, Ur, Edad, Idad” (“pine, ash, earth, wild cherry”). It’s like the alphabet song, but with groups of trees instead of melodic clusters—not that difficult for those who like puzzles.

But Ogham’s unique material structure makes it a little tougher than your average paper-bound alphabet. “Most inscriptions on stone are in the face of the stone,” says White. “But with Ogham, it wraps around the angled edge of the stone.” Because of this, Ogham provides a uniquely physical reading experience—after you’ve broken a sweat finding the right rock, proper analysis requires examining it on all sides. Inscriptions generally start on the lower left, sweep up along the top edge, and then go back down on the right.

An Ogham stone at Kilmalkedar. This one commemorates “Máel-Inbher, son of Broccán.” (Photo: Patrice78500/Public Domain)

This also presents particular challenges to archaeologists, says White. Although past scholars have come up with workarounds, the stones’ multi-dimensional orientation means ordinary drawings and photographs don’t get across the whole story. To fix this—and to preserve the inscriptions as the stones inevitably weather—White has spent the last couple of years making three-dimensional scans of all the ones she can get to, as part of the “Ogham in 3-D” project at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies’s School of Celtic Studies.

On scanning days, she and a surveyor from Ireland’s Discovery Programme lug their materials out to whatever front yard, remote hilltop, or sheep field holds the stone they need. “They’re very often in out-of-the-way places,” she says.”You have to make sure there’s no livestock in the field.” Because the 3-D scanner only works in completely blackness, they pitch a blackout tent over the stone, and let their equipment read it in the dark. If a stone is too big for the tent, they work at night.

Scanning in a stone at Arraglen. (Photo: Nora White/Ogham in 3-D)

Besides providing new linguistic insights and an accessible, complete corpus, White hopes their work may shed a little more light on Ogham’s mysterious past. Various legends present dramatic accounts: One says it was conjured up by the Celtic god of eloquence, Ogmios, who dragged his followers along by golden chains coming out of his tongue. Another holds that it was made up by a Scythian king named Fenius as an new ideal composite language, after the fall of the Tower of Babel destroyed the world’s existing ones.

Scholars have their own, slightly more grounded theories. Some speculate it was invented as a secret language, meant to be indecipherable by the neighboring Brits, who presented a constant threat of invasion and used the Latin alphabet. Others think it was created by Christian communities, who found it difficult to translate Gaelic sounds into Latin letters. White isn’t sure about the secret-code claims—the language seems too easy to learn for that—but then again, she’s not sure why Ogham exists at all. ”If they had this Latin alphabet, why create a whole new one for Irish?” she asks.

The answer may lay with the language’s new fans. Since the project launched, she’s heard from dozens of people asking her to come examine their local big, beat-up stone, to see if it’s got the right kind of slashes. There’s a strong pull to a language like that, unique and mystical and literally embedded in the landscape. “Maybe they just wanted to keep their own identity,” she says. “All we can do is speculate.” And, of course, keep reading.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook