See the Weird and Fascinating Deep-Sea Creatures That Live in Constant Darkness

When light is a commodity, evolution takes a strange turn.

A version of this story originally appeared on bioGraphic.com.

Although blue is the color most often associated with the world’s oceans, black is a far more apt descriptor for nearly 90 percent of our planet’s waters. Descending beneath the surface, the seemingly endless, light-flooded blue quickly fades, leaving nothing but utter darkness by a depth of roughly 200 meters (650 feet). Here, the largely unexplored and perpetually dark deep sea begins—a hidden, dreamlike world filled with fantastically weird creatures: gliding glass squid, flitting sea butterflies, and lurking viperfish.

Last winter, photographer and marine biologist Solvin Zankl joined a scientific expedition led by the GEOMAR research center in Germany to conduct deep sea biodiversity assessments around the islands of Cape Verde. The team explored the depths with cameras and lights, and used nets to bring an array of strange deep sea creatures to the surface. In his shipboard photography studio—outfitted with special aquariums and a powerful microscope—Zankl set out to capture the unique features and behaviors of these otherworldly organisms. This photo series offers rare glimpses of some of those creatures and the adaptations that enable them to survive and thrive in one of the planet’s most challenging environments.

Like many other deep-sea fishes, the Sloan’s viperfish (Chauliodus sloani) uses light-producing cells called photophores to lure unsuspecting prey toward its mouth. Once it catches its victim, the viperfish’s hinged teeth rotate inward to trap the animal and force it inescapably down the predator’s gullet.

The boxer snipe eel (Nemichthys curvirostris) belongs to a family of eels whose slender bodies taper nearly five feet, ending in threadlike tails. This body shape has earned the species the scientific name Nemichthys, or “filament fish.” The eel’s large eyes are adapted to capture every possible ray of light as they plumb the dinghy depths with curved, bill-like jaws. An exceedingly narrow body plan has resulted in a surprising location for the snipe eel’s anus: just behind the animal’s head.

Ghoulish in appearance, creatures like this ostracod have thrived for millennia as little more than floating heads. Lacking segmentation, their bodies and heads are merged, tucked away into a globular shell along with the creature’s appendages. This particular ostracod species (Gigantocypris muelleri) has mirror-like reflectors for eyes that it uses to locate tiny, floating creatures of the deep.

The triplewart sea devil (Cryptopsaras couesi), a species of anglerfish, uses a modified portion of its dorsal fin like a fishing pole to lure would-be prey toward its mouth. Only females are equipped with this bioluminescent, prey-baiting adaptation. The much smaller males, in contrast, are parasitic mates, holding on to females with a mouthful of spiny teeth. The tissues and circulatory systems of both fish eventually fuse together until the male has lost all internal organ function except sperm production.

The thieving pram bug (genus Phronima) parades through the sea in a stolen, translucent mobile home. Females devour the gelatinous innards of a jelly-like sea creature known as a salp before crawling inside the salp’s exoskeleton to lay eggs. The female hangs on to the hollowed nursery with hooked claws, and propels it through the water to provide her larvae with a constant flow of water and food.

Bacteria fluoresce like a beacon at the end of this anglerfish’s bioluminescent lure. It’s an elegant display of symbiosis—a mutually beneficial relationship between two species. Unsuspecting fish mistake the glowing tip for prey and find themselves quickly inside the oversized jaws and elastic stomach of the anglerfish (Cryptopsaras couesi).

This is no friendly embrace: A deep-sea squid (Chiroteuthis mega) wraps its tentacles around its prey. Light-producing cells called photophores likely lured this unfortunate fish into close proximity, allowing the soft-bodied squid to strike.

Bumping into a common fangtooth can be a deadly mistake for squid and smaller fish. Because the predator has poor eyesight, it relies on the motion-sensing cells along its lateral line—an enlarged sensory strip that runs the length of the fish’s body—to detect prey. Juveniles lose the bright, plankton-filtering gills seen on this individual when they mature and descend into some of the deepest depths of any known fish, often more than 5,000 meters (16,000 feet) beneath the ocean surface.

This larval longarm octopus (Macrotritopus defilippi) will ultimately live up to its name by developing long, thin arms that stretch up to seven times the length of the octopus’s body. Scientists have reported instances in which this species has avoided predation by mimicking the shape, color, and behavior of a flounder fish while moving across the sea floor.

Given its transparent body, the glass octopus (Vitreledonella richardi) remains one of the most elusive creatures of the deep sea. Rare photographs such as this reveal an array of opaque organs and a glimpse of its unusually shaped eyes. Scientists think the upward tilt and elongation of its rectangular eyes are adaptations to help the glass octopus avoid predation.

Trailing a barb from its lower jaw, the scaleless dragonfish (Bathophilus nigerrimus) bares spikey teeth to snatch prey, including crustaceans and small fish. Despite their menacing appearance, dragonfish actually have weak jaws. Ensuring that prey are well skewered is the key to this fish successfully bagging a meal.

The marine snail Atlanta inclinata undulates its fin-like foot to propel itself forward and keep from sinking into the dark depths. At night, the snail secretes long strands of floating mucus to help it stay buoyant. The whorl of its translucent shell offers a safe haven for retreat when the mollusk is threatened by a predator.

True to its name, the sea butterfly (Clio chaptali)—a member of a family of marine snails—seems to fly through water. Two fleshy “wings” have evolved from the snail’s foot, which allow it to flutter through the water column and passively feed on plankton while remaining protected inside its translucent shell.

Despite its small size, the eye-flash squid (Abralia veranyi) migrates great vertical distances through the water column. During the day, it remains at depth shrouded in darkness to avoid predation. At night, the tiny squid ascends to feed on shallow-dwelling invertebrates. Scientists believe the speckling of light-producing cells known as photophores on the underside of the body help break up the squid’s distinct silhouette and allow it blend in with the light-filled water above.

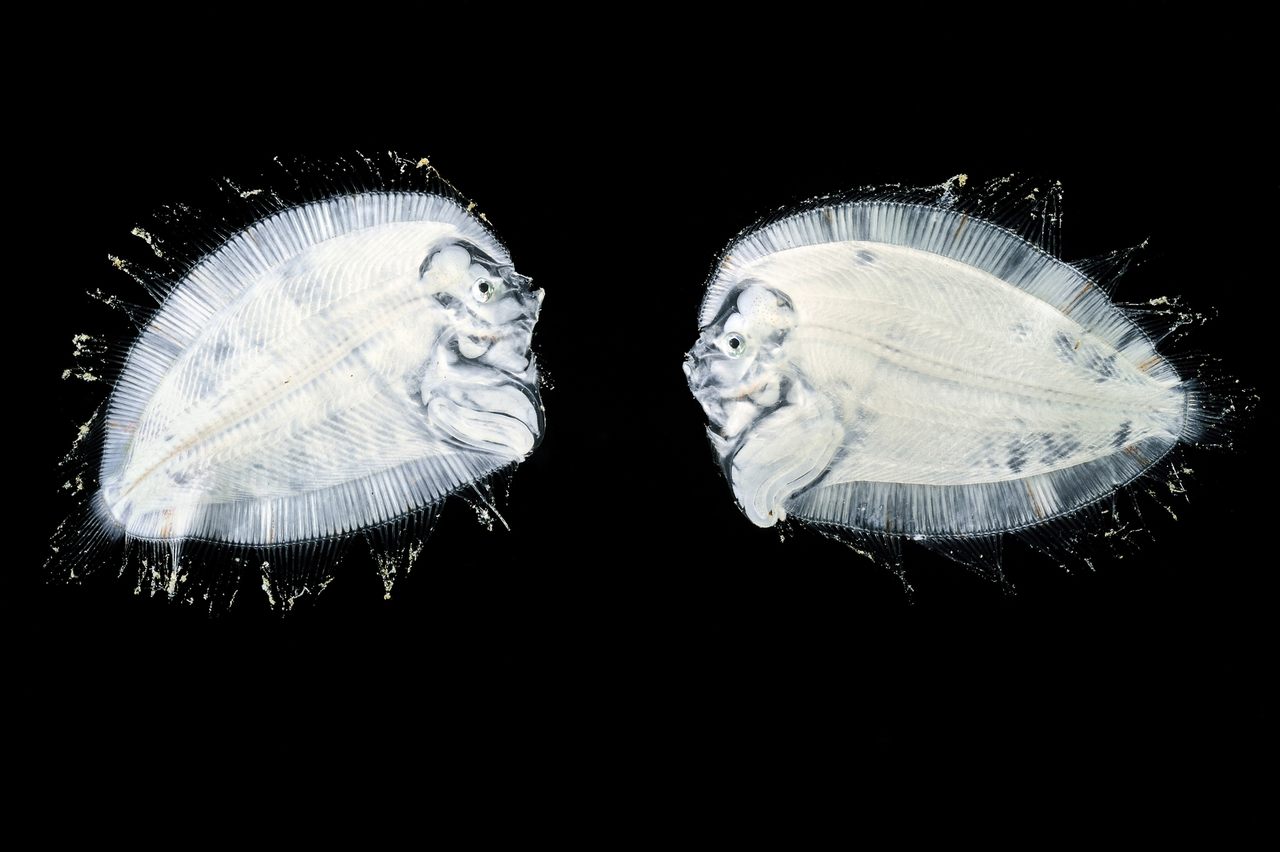

Deep sea eels endure such radical metamorphoses during their life cycle that at first scientists confused their various developmental forms for different species. While in its larval stage, this eel will spend significant time floating in the open ocean feeding only on tiny plankton and relying on its translucency to hide from predators.

Male copepods—tiny aquatic crustaceans—of the genus Sapphirina glint like colorful jewels one moment and are nearly invisible the next. Scientists only learned the details of this sea sapphire’s vanishing act a year ago. Cellular material measuring just nanometers in thickness separate the crystal plates of the copepod’s exoskeleton. The varying thickness of this material is what determines which wavelengths of light reflect back, and therefore which colors we see—if we see any at all.

This little larval prawn (Plesiopenaeus armatus) is rarely spotted in the wild—except in the gut contents of other species—and for centuries, scientists failed to recognize the larvae’s connection to its adult form. Genetic analysis has since solved the mystery, proving that a species formerly known as the “monster larvae,” with external armor and devilish horns, transforms into a ruby-red, shrimp-like creature as an adult.

This juvenile glass squid (Bathothauma lyromma) haunts the waters with stalked, bulbous eyes and two short arms. Like many glass squids, members of this species contain light-emitting organs on their lower surfaces, which are used to fool predators and obscure the silhouette of their eyes.

The most stunning feature of this deep-sea threadtail (Stylephorus chordatus) is undoubtedly its pair of green, telescopic eyes modified to capture the slightest traces of light. The threadtail creates negative pressure by ballooning its mouth cavity and sucking up unsuspecting prey. Despite its vacuum-like feeding habits, this only known member of the Steylphorus genus is named for the whip-like extension of its filamentous tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook