The Deck of Cards That Made Tarot A Global Phenomenon

(All photos: Atlas staff)

(All photos: Atlas staff)

Picture a deck of tarot cards. What do you see? Maybe the Magician in his rich red robes, right arm raised high above him. Or the skeleton on horseback for Death. Or maybe you think of The Hermit in grey, holding his lantern, walking with a staff, featured in the artwork for Led Zeppelin IV.

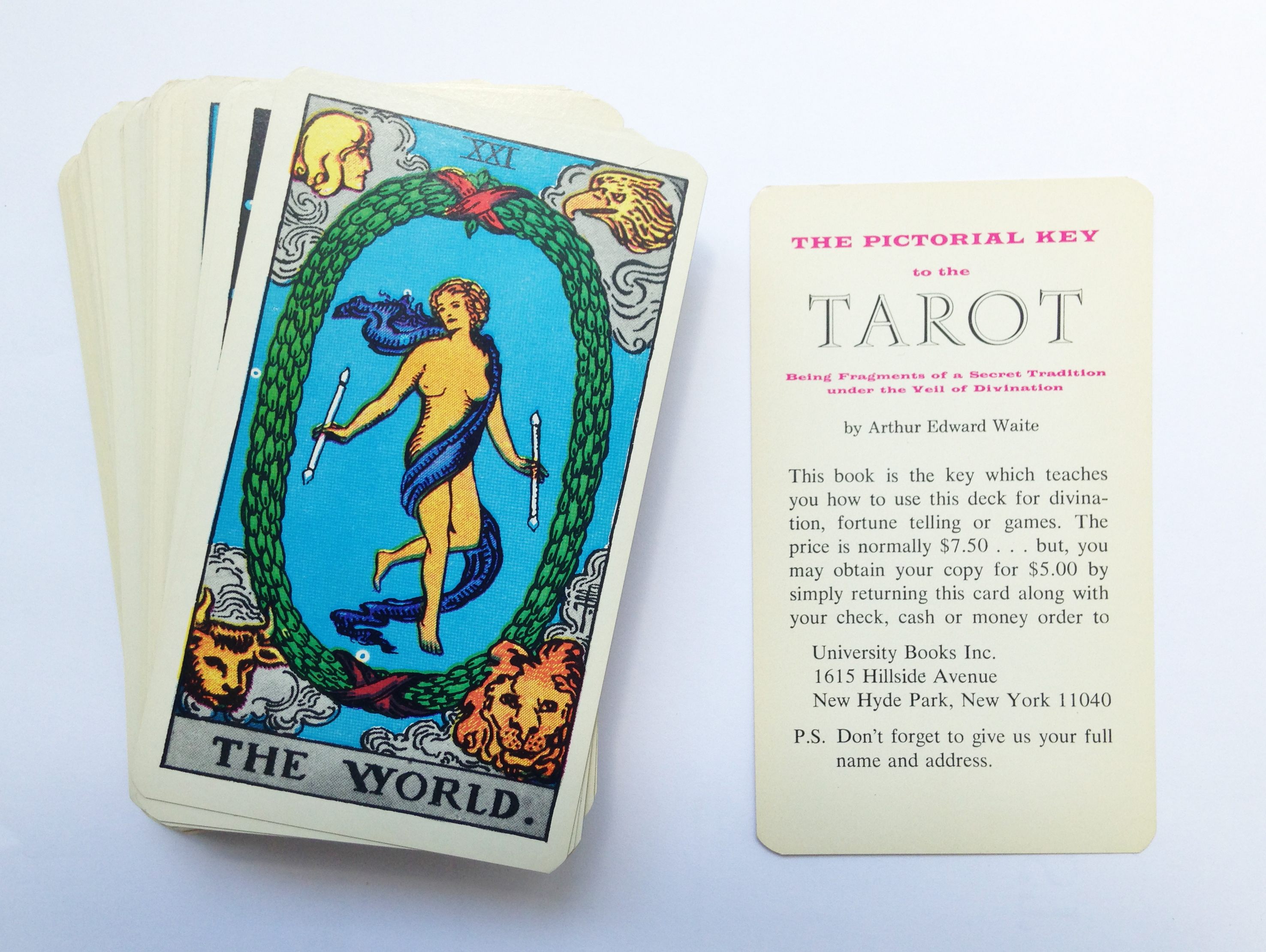

The funny thing is that those images don’t hail from some ancient text but from one particular deck of cards, a relatively recent one in the life of this medieval form of entertainment: The Rider (or Rider-Waite-Smith) Tarot. That you can visualize a tarot card at all is likely due to one man, an American business man named Stuart R. Kaplan, founder and chairman of U.S. Games Systems, Inc., which has been producing and selling the Rider-Waite deck since 1970.

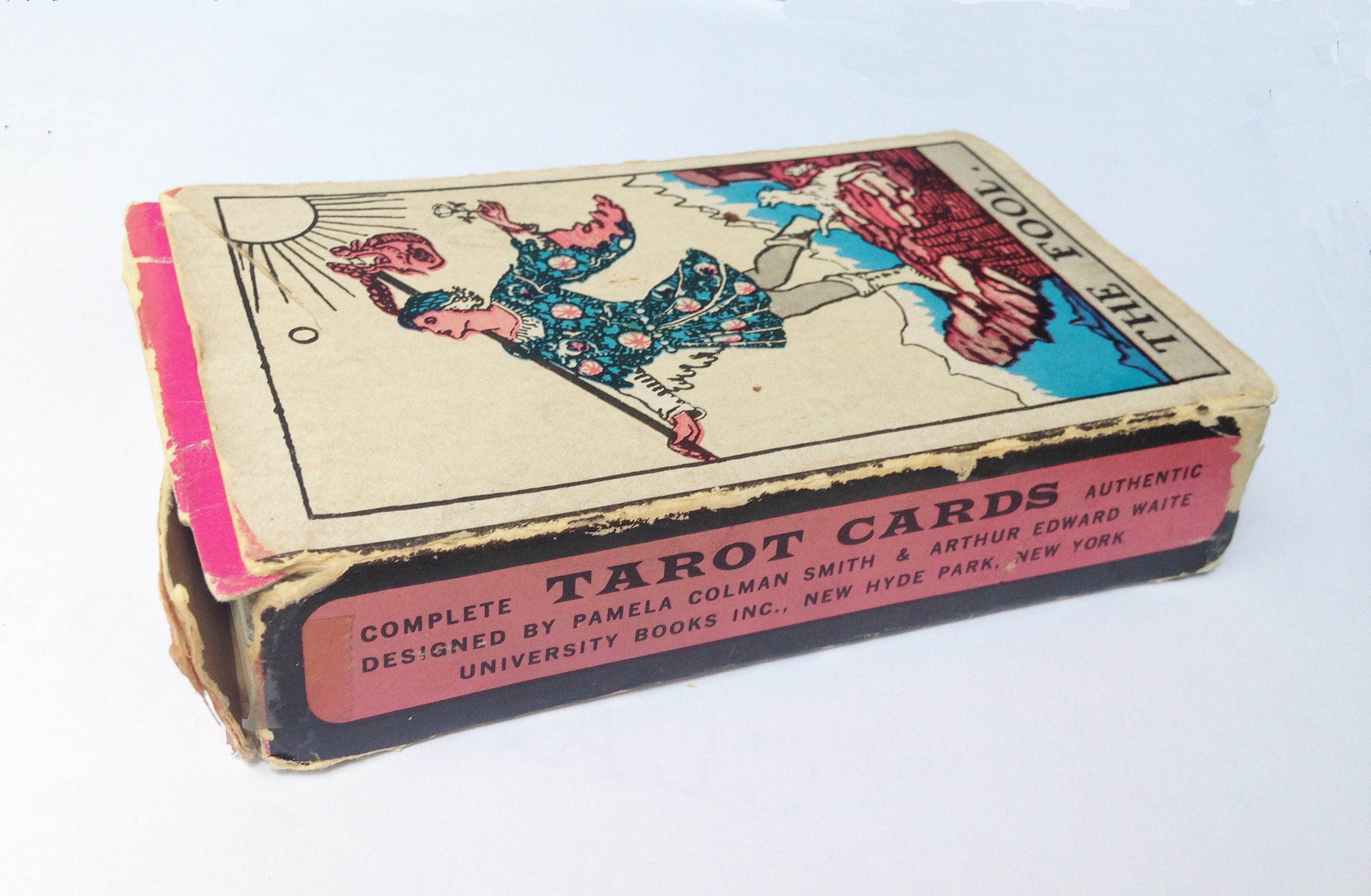

Well, him and the artist, Pamela Colman Smith, responsible for the 78 original drawings that make up the deck.

Tarot itself is a fairly simple game. The instructions, with each card placed in its position having a particular purpose, are strikingly simple, easy for even a first timer. With time and practice, the cards may begin to really convey meaning, asking us to look deeper at ourselves and our motives, and nudging us in the correct direction. But it took an unholy trinity to bring this to the American public. The most famous and popular tarot deck in the world, the first ever printed in English, the Rider-Waite tarot is a product of the intuitive thoughtfulness of an American-born occult scholar in late 19th century London, a British-born creative visual genius who studied art in New York City and lived in Jamaica, and a businessman whose first book was about coal mining techniques who happened upon a set of tarot cards at a toy fair in the late 1960s. These three people, essentially, are the only reason any of us know much of anything about tarot.

Tarot cards have a long story and a short one. The long one begins in 15th century Europe, where the 78 card deck—four suits (Wands, Cups, Swords, Pentacles) of 10 “pip”cards running from Ace to ten, each with an additional four “face”cards (King, Queen, Knight, and Jack) plus 21 Trump cards known as the Major Arcana, plus the Fool—form the traditional tarot deck. Without the Major Arcana, the cards of Tarot are roughly aligned with a standard playing card deck, which has its roots in France a few hundred years earlier. By the 15th century, tarot cards were widely used for popular trick-taking games such as French Tarot (which is still widely played) and the Italian game tarochini.

The shorter story, however, is how Tarot came to be used in fortune telling. In 1781, when Antoine Court de Gébelin, a French Freemason and Protestant pastor published a book called Le Monde Primitif, tracing the mysticisms of the ancient world and their surviving traces in the modern. Among them, he included the famous French playing card deck, the Tarot de Marseilles, which he connected to the Egyptian deities Isis and Thoth. Though his musings on the subject haven’t been found to be based on any evidence, tarot’s association with the mystical was now set. A few other, mostly French, writers and occultists followed in writing treatises and books on the occult leanings and possibilities offered by the cards, but tarot readings were hardly mainstream.

In 19th century England, however, interest verging on a mania raged for all things occult. Suddenly, worlds of knowledge, coupled with current thinking on the psychology of the human mind opened up, and people of all walks of life became enamored with contacting the spirit world to find out the future or to commune with the dead. Christians began reading the Kabbalah. Interest in photographing ghosts rose.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, devoted to study of the occult, and one of the first organizations of its type to fully admit women in addition to men, was founded with its first temple in London in 1888. Called the Isis-Urania Temple, it was founded by three Freemasons who were also members of the Rosicrucian Society of England, an esoteric Christian order. Early members of the Golden Dawn included William Butler Yeats, Aleister Crowley, and Arthur Edward Waite. Several splinter temples formed over disputes—largely seeming to do with the later famous occultist Aleister Crowley, who was infamous during his lifetime for his experimentation with drugs, his libertine lifestyle, and his outspoken minority opinion for the time that homosexual desires should never be repressed or ignored. One of the reformed orders included who would become the founding team of the modern English language tarot: Arthur Edward Waite and Pamela Colman Smith.

Arthur Edward Waite was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1857 to an American father and a British mother. Arthur’s father died before he was two, leaving his mother a widow. She returned with her family to England, where Arthur spent the rest of his life. He apparently became interested in the occult when his sister died at a young age in 1874. Eventually, he joined up with the Order of the Golden Dawn, later also becoming a Freemason and then a Rosicrucian. As far as occult topics were concerned, Waite’s interests were varied and far-reaching. He wrote books on topics such as the Kabbalah, mysticism, ceremonial magic, and the Holy Grail, beginning in the late 1880s. His work was well received in mystic and academic circles, and he was soon one of the best known authorities on such topics. One of his books, Book of Black Magic and Pacts (1898) led a very young Aleister Crowley to write to Waite for advice. Eventually, through their associations with the various societies and brotherhoods, the two sparred and became “enemies,”with Crowley attacking Waite in his writings for years. There is a hint of theatrics to all of this, and the contemplative Waite seems not to have taken the bait for the most part. Certainly it didn’t slow down the prolific output of either.

Which brings us back to the tarot cards. In 1908 the British Museum acquired black and white photographs of a full deck of tarot cards now known as the Sola-Busca deck. The deck, which dates from around 1490, was extremely special, and Arthur Edward Waite would have known that when he went to see the photographs on exhibition at the museum soon after their arrival.

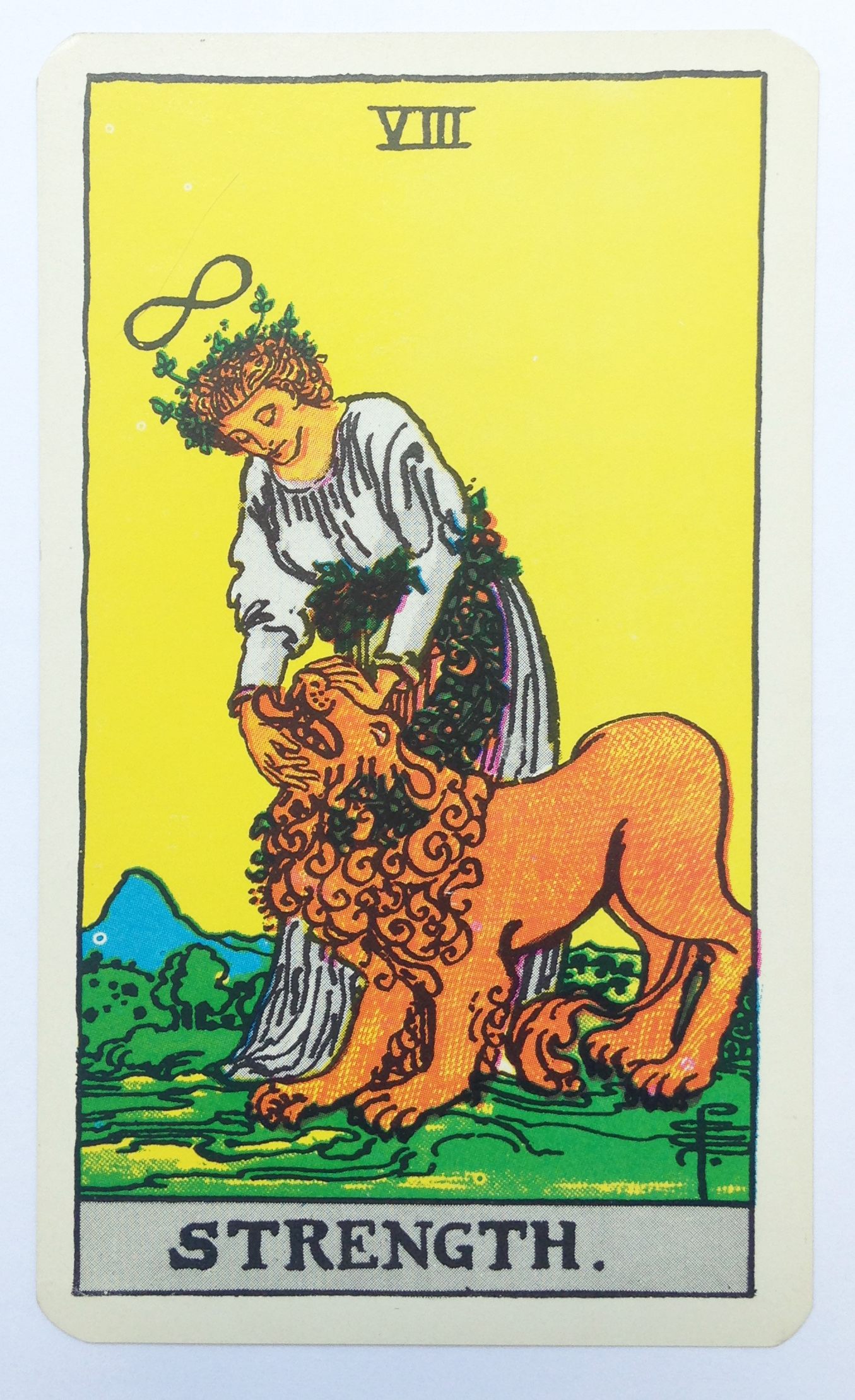

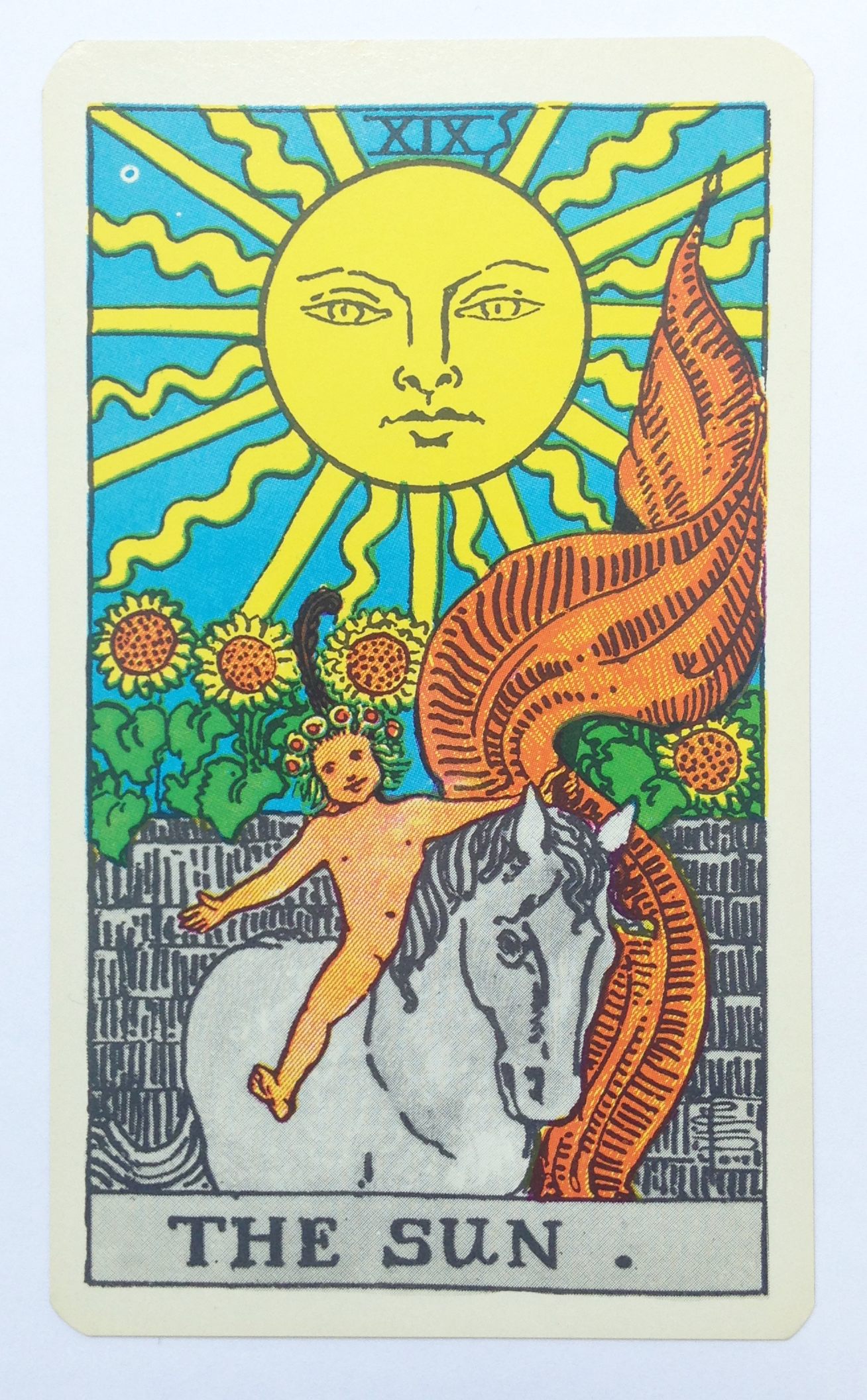

It is, first and foremost, the earliest extant complete tarot deck. It is also, significantly, the first deck to illustrate all of the “pip”cards: previous decks had all had a 2 of Swords, but instead of a full illustration, there would simply be two swords on the card. This deck illustrated all cards equally, with fully realized illustrations, setting its suits apart from regular old playing cards, and thereby also obscuring their relationship to the layman’s eyes. The Sola-Busca deck would prove to be inspirational to Pamela Colman Smith, the artist Waite chose to draw his deck, and in fact several of the cards in both decks are almost identical in design.

Smith’s story begins in London, where she was born to an American father and a Jamaican mother. She travelled between Jamaica, London, and New York as a child, and eventually studied art at the Pratt Institute in New York City under Arthur Wesley Dowell, though she didn’t earn a degree. She set up shop as a commercial illustrator in London and did the art for a volume of William Butler Yeats verse, several magazines, and eventually illustrated Bram Stoker’s last published work, The Lair of the White Worm, in 1911. Smith’s art was colorful and unique, and in 1907 Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer (and eventual husband of Georgia O’Keefe) gave Smith her own show at his Photo-Secession Gallery, in his first non-photographic exhibit. Like Waite, Smith’s interests were varied, and she published her own books on Jamaican folklore, as well as (briefly) her own magazine, The Green Sheaf, each issue of which bore the words, “my sheaf is small, but it is green.” Smith was known in her own time to have a “second sight,”and to paint pictures based on visions she saw while listening to music. She was ushered into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn by Yeats, which she joined in 1901. She splintered off with Waite when he left the Order to form his own incarnation.

It was, then, through their association with one another that Waite came to commission Smith to create 78 original drawings for the new tarot deck, the first one in English, which he wished to create. Unlike most previous decks, Waite’s tarot would be primarily for divination and so the images would be intentionally laden with meaning. In six months, Smith completed the work, seemingly from written instructions by Waite for the Major Arcana, letting her imagination fully guide the rest of the deck. The Rider-Waite deck, as it came to be known, was published in 1909 by Rider Company in England. The next year, Waite published a small guide to reading the cards for Rider, and in 1911 he published his full book on the subject, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot.

Smith’s drawings, under the guidance of Waite—who proposed a thoughtful way for everyday people to read the cards years before the industry of professional tarot readers sprang up—are vibrant and intuitive, and though Waite’s aim was to produce a beautiful, art-minded deck (success!) what happened was that the two created a deck capable of passing, eventually, into the mainstream consciousness.

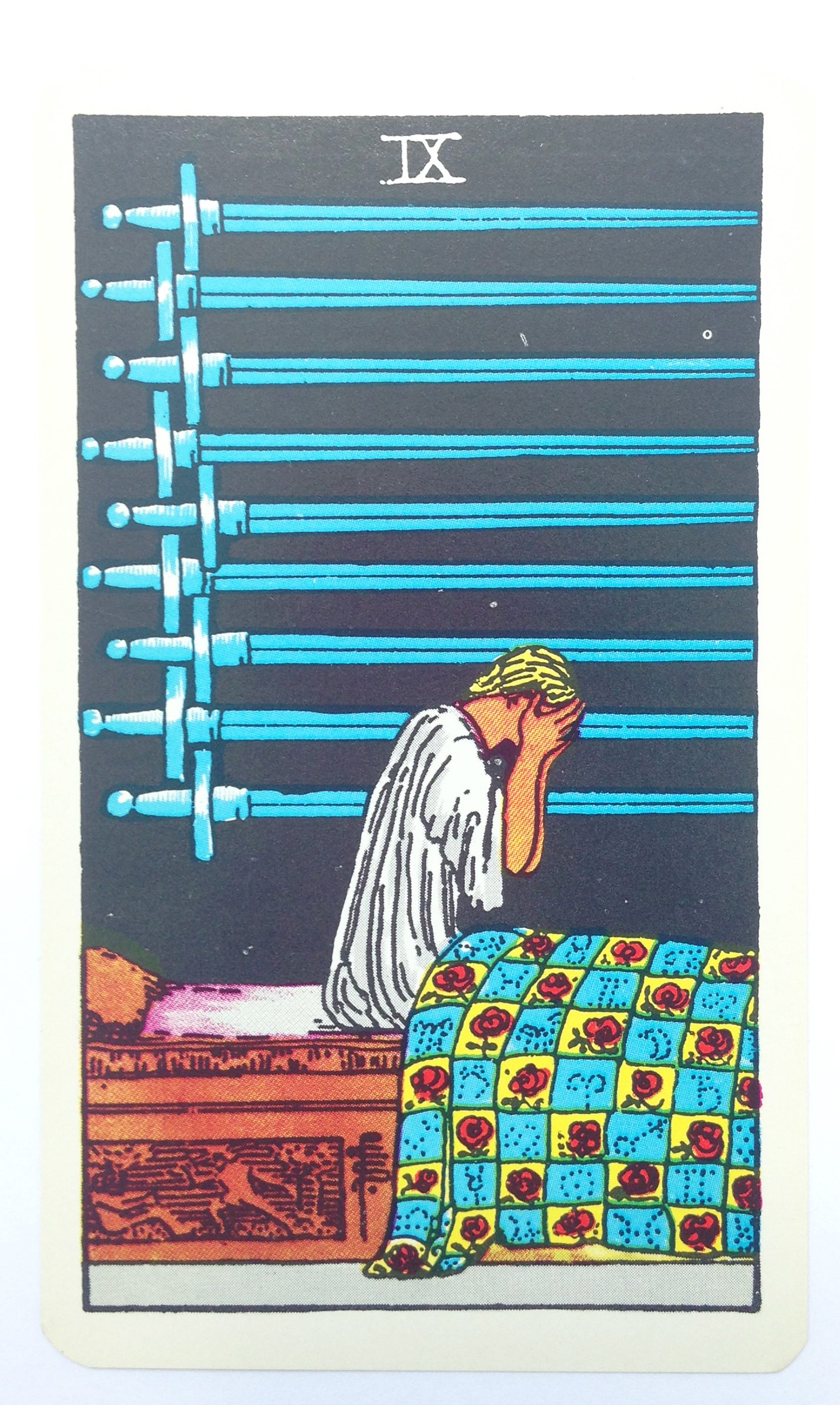

Each of Smith’s drawings conjures enough of Waite’s key phrases—the divinatory meanings of the cards—that the pure novice is likely to guess at them on a cursory peek at the image itself. Take the Nine of Swords, for example. The image, on a stark black background, nine swords in parallel behind a figure, sitting up from the covers in bed, head in hands. The image is desolate: something awakens him or her (and so many of Smith’s figures are androgynous) in the dead of night. Is it worry or fear, or is it both? One looks at the card and sympathizes: we have all had such sleepless nights of pondering, either over the past which cannot be changed, or the present, which is confusing. You can see this in the card without ever glimpsing Waite’s accompanying text.

But here is his text:

“Divinatory Meanings: Death, failure, miscarriage, delay, deception, disappointment, despair. Reversed (when the card appears upside down in a reading): Imprisonment, suspicion, doubt, reasonable fear, shame.”

A complete newcomer to the tarot, if asked to describe the emotions the card generates might not come up with these exact words, but the meaning is certainly apparent, and obvious. And so goes each and every card, even the ones which describe more abstract thoughts and feelings. It was this mind-melding of Waite and Smith which produced the deck of tarot cards which most of us now know as “the tarot.”

When Arthur Waite died in 1942, his obituary, published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, called him the author of “many books on occult phenomenon.”There was no mention of his tarot deck. When Pamela Colman Smith died 16 years later… well, I can find no obituary for Smith. Tarot cards, never mainstream, didn’t exactly disappear, but they also did not flourish by any means.

Enter Stuart R. Kaplan, a graduate of the Wharton School of Business in 1955. “I’m all yours,”he tells me after a few weeks of missed connections on the phone, before launching into his personal history. Kaplan was working in New York City in the late 1960s, managing mines in West Virginia and Pennsylvania when he went to Germany on a business trip in 1968, ending up, out of curiosity, on his free time, at the Nuremberg Toy Fair. He wasn’t completely unknown in the world of games: he’d created his own Student Survival board game in the U.S., and it had seen moderate success. Still, when he happened upon the exhibition booth of the Swiss AG Müller & Cie, he found an odd deck of cards, and he was intrigued.

Kaplan didn’t know much of anything about tarot at that point, but cut a deal to import a few thousand of the decks—known as the Swiss 1JJ tarot—to sell in the United States. Kaplan targeted large bookstores such as Brentano’s, and was successful enough in his efforts that he began looking for other tarot decks to import. In the meantime, he wrote the first of his many, many books on tarot: Tarot Cards for Fun and Fortune Telling, published in 1970. In 1971 he began to sell a Marseilles-style tarot deck, and wrote a second, more detailed book, Tarot Classic. This book delved into the history of tarot, and for the first time Kaplan wrote about Arthur Edward Waite. Soon after, Kaplan negotiated with the British company that held rights to the Rider-Waite deck, which he says wasn’t selling decks at that point. Kaplan wouldn’t import the cards. Working with Rider and the blessing of Waite’s only surviving heir, his daughter Sybil, Kaplan would own the rights to publish them in the United States.

The Rider-Waite tarot, and tarot generally, had never been widely in circulation. But Kaplan had now been, for several years, selling hundreds of thousands of tarot decks quietly from the offices of his new company, U.S. Games Systems, Inc. in Stamford, Connecticut. And when he began selling Waite’s deck, there was a slow but sure explosion. “I think the full illustrations of all the cards, including the pips, is the key to the deck’s longevity and popularity,” Kaplan says. U.S. Games, which currently has about 50 decks in print and has published hundreds over the years, prints decks for a few years and then refreshes. Only the Rider-Waite decks have never gone out of print, and demand for them, Kaplan says, is always consistent.

By the mid-1970s, tarot was on its way to becoming popular in the mainstream, and almost everyone’s tarot cards came from the same place, U.S. Games Systems, Inc. “We have prevailed because we have devoted all of our attention to tarot cards,”Kaplan says. “Companies come and go: they’ll print one deck and then be gone. We have never given up,” he goes on, and because of Kaplan and his company, tarot cards are widely available and cheap. “If I see a deck on sale on eBay,” Kaplan, also an avid collector of games, rare tarot cards, and books says, “and it’s $100 or something, that upsets me. If there is a demand for an old deck that’s out of print then we’ll just bring it back. The decks aren’t supposed to be so expensive.”

Kaplan sold parts of his own personal collection of rare tarot artifacts at Christie’s in 2006, with some individual cards selling for thousands of dollars. U.S. Games sells new decks for $20. “I think tarot is popular because each deck is an unpaged book,” Kaplan says. “Shuffle them and you’ll get a new story every time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook