The Forgotten Midwest Craze for Building Palaces Out of Grain

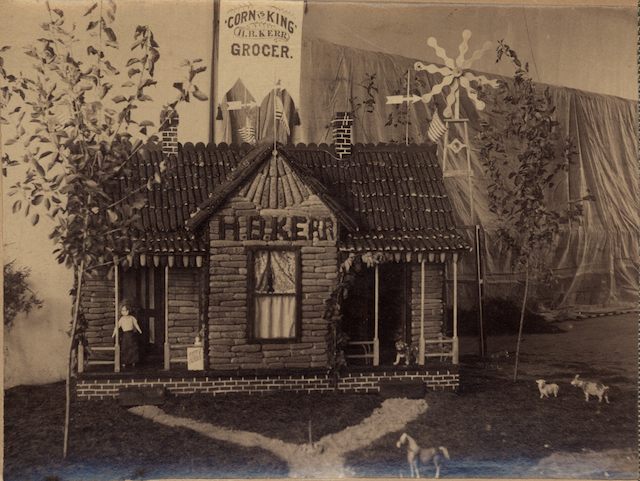

Not all Corn Palaces were quite so grand. (Photo: Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer)

In 1890, Forest City, Iowa, built a palace–not of stone, or wood, or brick, but of flax.

There was, one visitor reported, “flax for siding and flax for shingles, flax for decoration outside and inside, on the pillars and along the rafters, on the stairs and overhead, pendant from the ceiling, a world of flax in all the devices possible to fertile fancy.”

The inventive structure in Iowa was not the only one of its kind. In the late 1880s, the midwest was seized by a craze for building palaces out of grains—hay, bluegrass, alfalfa, and corn, corn, corn.

The Forest City Flax Palace (Photo: Forest City Historical Society)

These were fairytale palaces, rising out of the prairie like illusions and topped by towers, turrets and spiral domes. A grain palace might have a promenade three stories up, or a passage wide enough to pass a streetcar through.

These grand buildings were meant to show off their cities’ bounty and to lure settlers to the otherwise foreboding plains. In total, there were at least 35 built, in 24 cities, from South Dakota to Texas, and as far east as Illinois.

The first Sioux City Corn Palace (Photo: NYPL)

The first, built in 1887, was Sioux City’s corn palace, which spanned more than 18,000 square feet, rose 100 feet high and cost $25,000–hundreds of thousands in today’s dollars. In the year it was built, a drought had devastated crops across the middle of the country. But for some reason, Sioux City’s part of Iowa was spared and even had an excess of corn.

The city wanted to signal that life in the Midwest wasn’t as dreary and desperate as it might seem, and, as Pamela H. Simpson writes in Corn Palaces and Butter Queens, the idea for the palace came from a town meeting, at which one enterprising man asked “why, if Saint Paul and Toronto could have ice palaces, Sioux City couldn’t have a corn palace.”

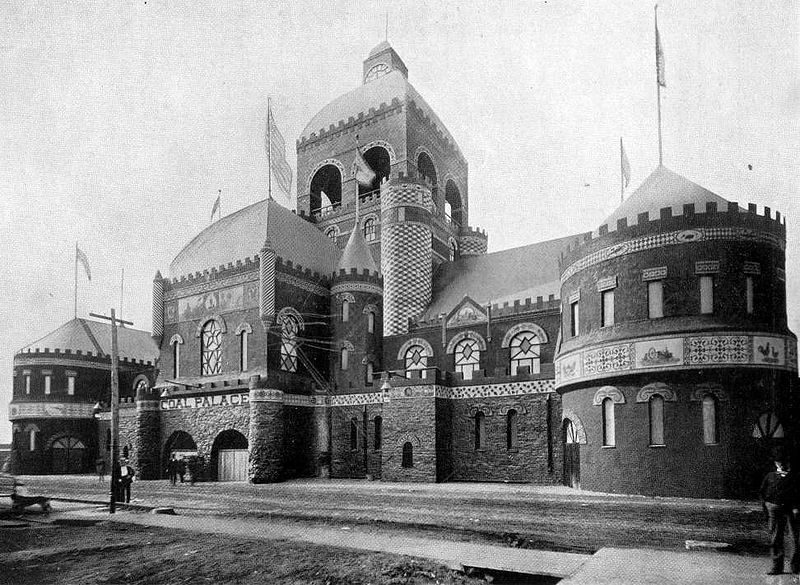

The palace the city built was such a success that President Grover Cleveland came to visit, and almost immediately, other cities started work on their own agricultural edifices. In 1889, there was a Texas Spring Palace, decorated not just with corn but with oats, cactus, moss and johnson grass. Ottumwa, Iowa, made a Coal Palace, built on a foundation of coal and walled with coal mixed with mortar. By 1890, there was a bluegrass palace, a hay palace, Forest City’s flax palace, and a sugar beet palace in Grand Island, Nebraska, followed in the next years by a grain palace, broom palace, and more and more corn palaces.

Inside the Flax Palace (Photo: Forest City Historical Society)

Yet even though the palaces attracted people from far-away states and helped otherwise unknown cities make a name from themselves, they also had some drawbacks. Their creators didn’t always break even. With grain exteriors built on wood scaffolding, they were terrible fire hazards. Inconveniently, the giant piles of outdoor grain were also a feast for rats, birds and other prairie creatures.

After its fifth Corn Palace, Sioux City gave up the tradition. But in 1892 Mitchell, South Dakota, then a town of a just 3,000 people, took up the mantle and built its first Corn Palace. In 1919, it decided to make the palace a permanent feature of the town.

By then, the mania for grain palaces was passing; today Mitchell’s is the only one standing. The rest of the midwest’s regal, grain-covered marvels disappeared, preserved only in a few fading pictures.

The Coal Palace (Photo: Wikimedia)

The Grand Island Sugar Beet Palace. The inside was extensively decorated with sugar beets, as well as maps made of corn and figures made of grain. (Photo: Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer)

An Alfalfa Palace (Photo: Public domain)

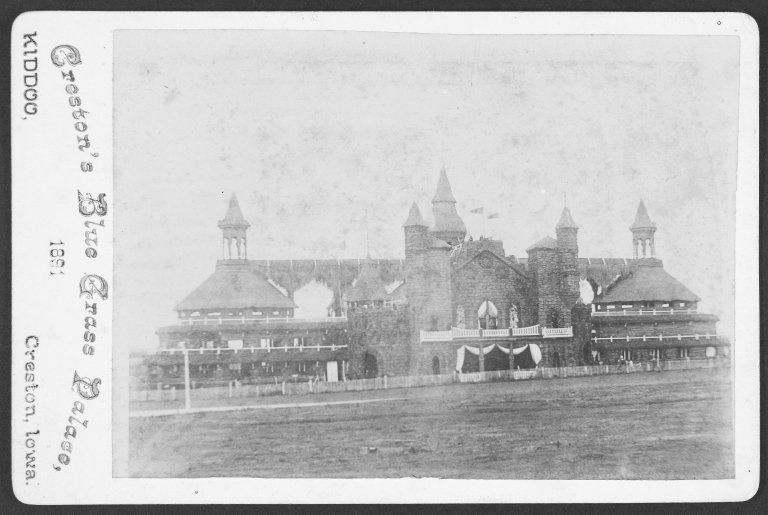

Creston, Ia., built a Blue Grass Palace (Image: KU Library)

Another view of the Flax Palace (Photo: Forest City Historical Society)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook