The Great Failure of Andrew Carnegie’s Simplified Spelling Lobby

An 1886 illustration of Noah Webster “the schoolmaster of the Republic”. (Photo: Library of Congress)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

In their own quiet way, spelling and grammar are each forms of lobbying. We treat language as an immutable fact, but it started out as a variety of opinions on what things should be called. And those opinions, like a diamond pressed into form, slowly molded into a definitive shape.

But even though language started from dissent, there’s a limit to how much dissent we can tolerate–hence the popularity of dictionaries and style guides, which draw up a map for how we use words on a daily basis.

At times, though, the push for changes to the English language has gotten extremely political. And we can thank some of the most prominent Americans in history for that.

Title page of Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language, circa 1830–1840. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

One of those Americans was Noah Webster, who created the first truly American dictionary in 1806. A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language was an extremely opinionated work that tried to clean up some of the English language’s biggest problems.

“The orthography of our language is extremely irregular; and many fruitless attempts have been made to reform it,” Webster argued in an introductory essay. “The utility and expedience of such reform have been controverted, and both sides of the question have been maintained with no inconsiderable zeal.”

Webster attempted to scale back the complexities that pockmarked the English language at the time, while calling out “the corruption of language by means of heedless writers.”

For example, it didn’t make sense to him that “colour” had a u in it, so he just removed it. Likewise, it seemed strange that “publick” had the extra k, so off it went.

Webster’s strategy of whittling away at letters was controversial, but it largely worked; not every change took, but a number of them did. His work inspired later spelling reformers–particularly Andrew Carnegie, who spent a lot more money and had a lot less luck than Webster did.

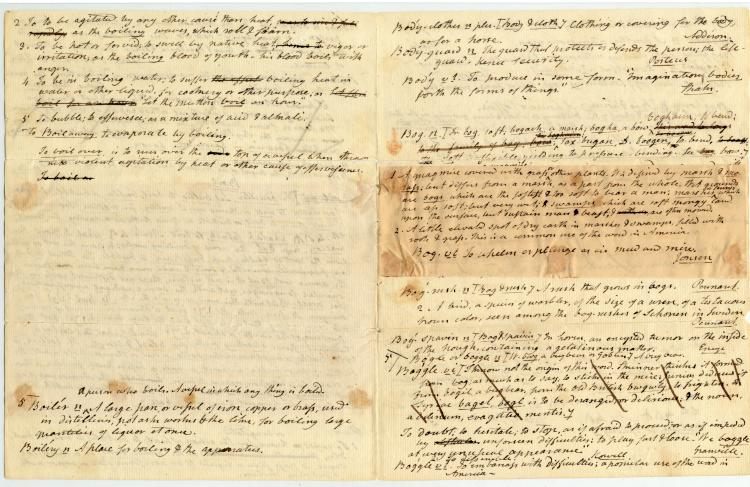

Handwritten drafts of dictionary entries written by Noah Webster, c.1790. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

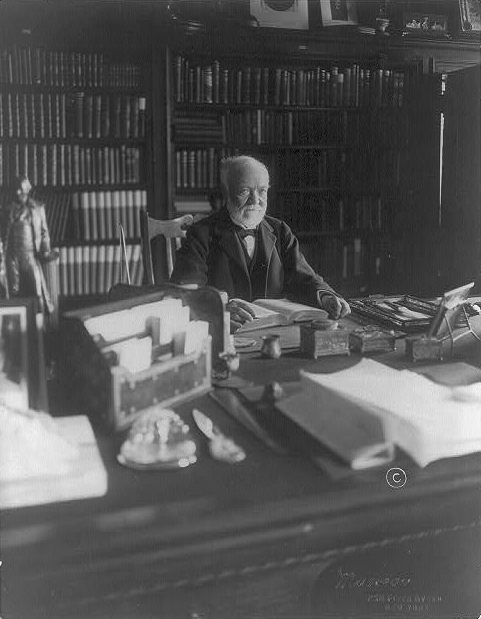

In a lot of ways, Carnegie was a study in contradictions. He was an empire-builder who wanted to give away the fruits of his labor as soon as he received them. He was a progressively-minded philanthropist whose company oversaw one of the deadliest anti-unionization battles in U.S. history–a battle that, to be fair, he deeply regretted after the fact.

He was also was a man who built thousands of libraries in his name–more than 2,500 libraries, in fact–but who also devoted himself to making all those books obsolete, by rewriting the English language to be as simple as possible.

That desire for a simpler English led Carnegie to help found and fund the Simplified Spelling Board, an organization designed to make the language more obvious and phonetic. Carnegie’s reason for funding the organization in 1906 was an attempt to help push forward the idea of making English the global language.

His approach was even more aggressive than Webster’s. The organization he created had no interest in graceful-looking words. The Simplified Spelling Board eyed changes that would have made the dictionary fully phonetic, with little variation from the way words are actually said. Words like “woe” would have become “wo” and “though” would have devolved into “tho.”

Andrew Carnegie seated at his desk, 1913. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Carnegie, being a rich man with a lot of political clout, knew that influence was the key factor necessary to push these ideas “thru.” So his organization started by trying to convince a number of famous authors to begin to use the new spellings in their books–and scored big names like Mark Twain, convincing them to simplify a handful of particularly frustrating words like “altho” and “catalog.”

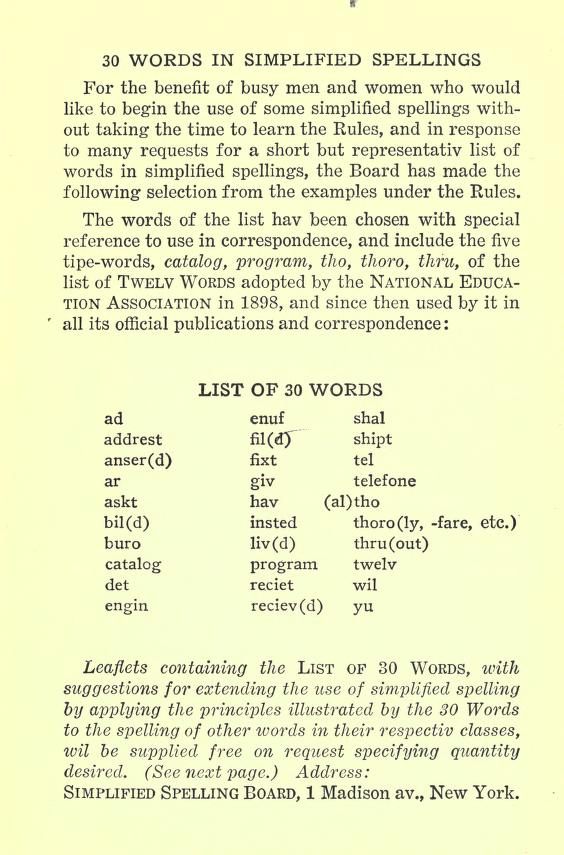

But then the board bit off more than the American public could chew. Soon, the group’s list of 12 words grew to more than 300, and the influence game reached all the way to Teddy Roosevelt, who became a big fan of the concept and soon ordered the Government Printing Office to use the list of words for all official government documents.

As anyone who follows politics today can tell you, there’s nothing that some people hate more than feeling like they’re being told what to do by the federal government. Soon, both Congress and the media were hating on the idea of a dramatic attempt to Americanize the English language. Within weeks of Roosevelt’s call, the House passed a bill to prevent the change from going through. The president, sensing a losing battle was on his hands, quickly backed down.

“I am sory as a dog,” Twain wrote to Carnegie of the failure. “For I do lov revolutions and violense.”

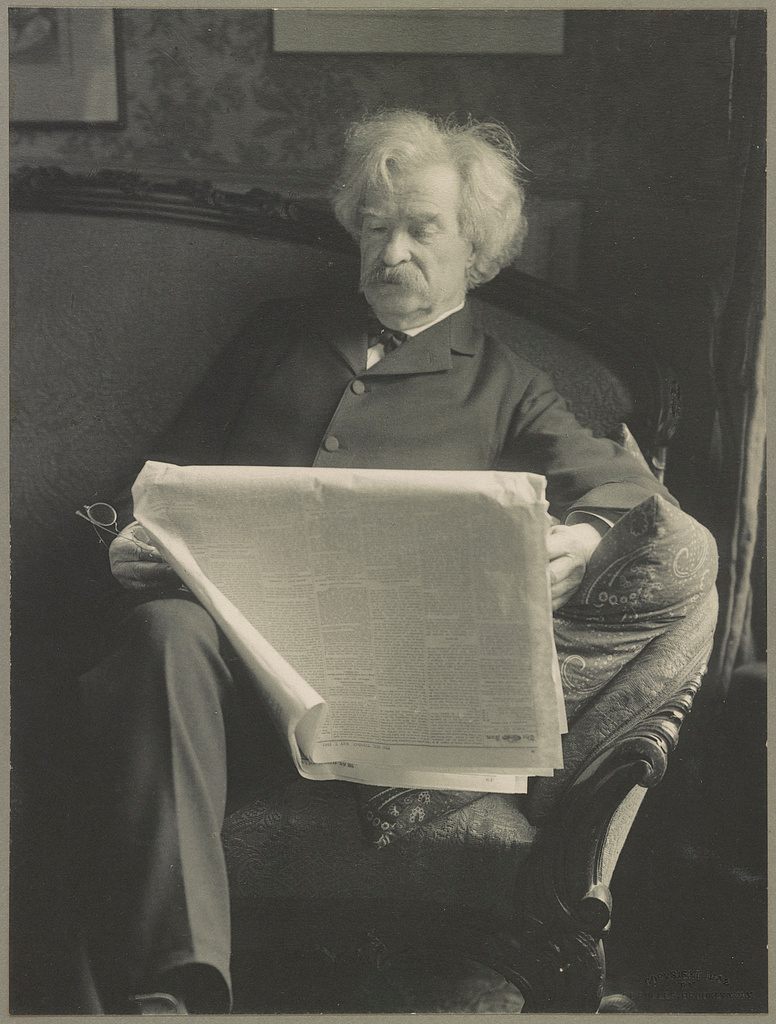

Mark Twain, reading a newspaper, 1902. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Despite his embarrassing loss on the phonetics front, Carnegie kept funding the Simplified Spelling Board for nearly a decade afterwards, stopping only after it became inescapably clear that his attempt to influence the country to spell differently had failed.

“I think I hav been patient long enuf,” he wrote as he cancelled the funding in 1915. “I hav a much better use for twenty-five thousand dollars a year.”

Back then, $25,000 was real money, the equivalent of more than half a million dollars now. It’s a crazy amount of money to spend on anything, let alone spelling.

The Simplified Spelling Board didn’t totally die out until a few years after Carnegie’s pocketbook closed. As one of its final acts, the group released a document it called the Handbook of Simplified Spelling.

“Our spelling has become so irrational that we ar never sure how to spel a new word when we hear it, or how to pronounce a new word when we read it,” the 1920 book read.

The Simplified Spelling Board ended in failure soon after the book was printed.

From The Handbook of Simplified Spelling, with a “representativ” list. (Photo: Internet Archive)

These days, the spelling and grammar partisans still exist–with a little less anger and frustration driving their approach–in newsrooms nationwide. Their weapon of choice? The Associated Press Stylebook.

Unfortunately, the AP Stylebook doesn’t always love them back.

“Whenever a change is made to the AP Stylebook, I curl up in the shape of a comma and emit loud cries,” Washington Post humorist Alexandra Petri wrote after the AP decided that “more than” and “over” were interchangeable in front of numbers.

Others still, say that the AP Stylebook dilutes its value by including every topic under the sun in its purview. “While you’re trying to stay relevant, you’re needlessly filling my mind with information that is easily obtained elsewhere,” wrote Daniel Hunt, a Sacramento Bee designer and copy editor, in an American Society of Copy Editors blog post.

Sometimes, the issue isn’t so much relevance as politics; the AP will occasionally change terms when a phrase has become loaded politically. When “climate change denier” was replaced with the softer “climate change doubter” a couple of months ago, a few journalists disapproved in strong terms.

“Would we talk about gravity doubters? What about people who doubt the link between smoking and lung cancer? In no other circumstance would the complete rejection of science be treated so gently,” wrote the Huffington Post’s Ryan Grim.

But no linguistic change drives editors crazy like the Oxford comma, the comma that goes before the final item in a list. Roy Peter Clark, an educator at the Poynter Institute, argues that the AP Stylebook’s longstanding stance against the Oxford comma has frustrated him, left his copy missing something, and is slowly going out of style.

He has commonly left them in his copy as a protest. “For three decades, I have included that final comma in a series only to watch helplessly as my journalism editors pluck it out with tweezers,” Clark wrote last year.

The Associated Press is no Simplified Spelling Board, and nor should it be. But there are plenty of active organizations out there that have taken up the mantle for phonetic English. Problem is, they don’t have anyone near as powerful as Andrew Carnegie, Theodore Roosevelt, or Mark Twain to make their case. So they’ve been forced to switch strategies. One of the strategies these groups have undertaken is to protest spelling bees.

In 2010, protesters from the American Literacy Council and the English Spelling Society descended on the Scripps National Spelling Bee, arguing that the whole idea behind the contest was a sham, and that words should be more phonetic.

“Enuf is enuf. Enough is too much,” one of their signs said.

New Yorker writer Eileen Reynolds, responding to the bizarre protest, stated the obvious: the mission is a lost cause, and the final result would be nothing worth celebrating.

“The spellings of words tell stories. They tell us something about the history of words–the long or short journeys they took before reaching us,” she wrote. “I’ll cling to the dreaded ough endings for as long as I live, because they remind me of the fascinating and chaotic period of the language’s history known as Middle English.”

Perhaps words aren’t designed to be perfectly phonetic. Maybe we just have to accept their wrinkles for what they “ar.”

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook