The Lost Mushroom Masterpiece Unearthed in a Dusty Drawer

How an obscure woman mycologist left her mark on fungi.

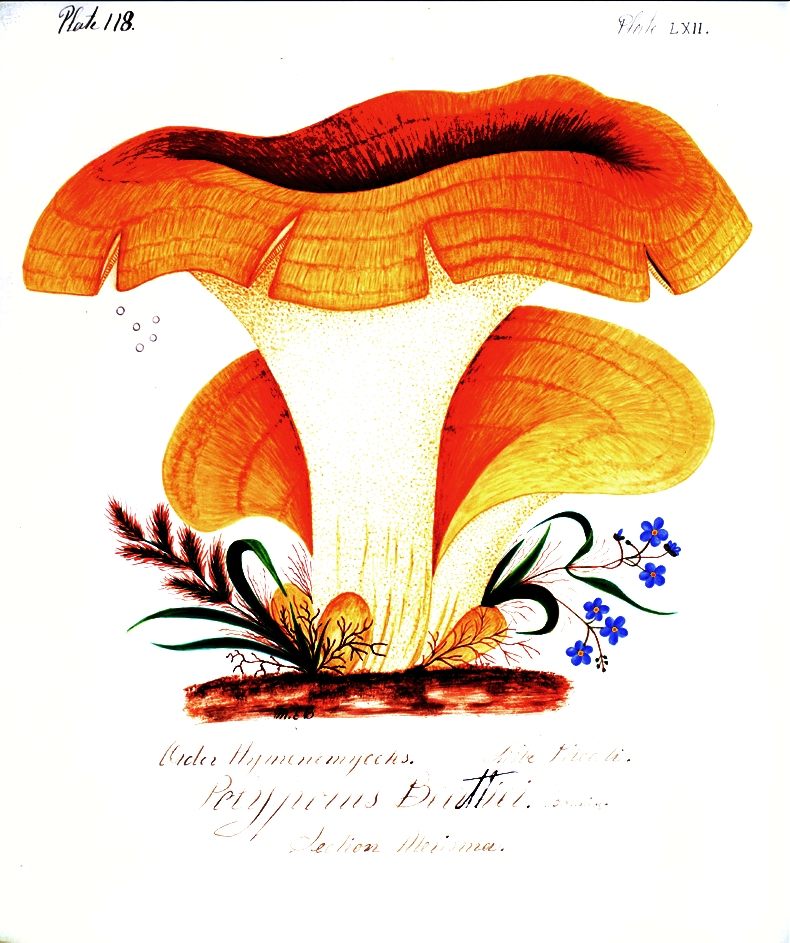

An illustration of Polyporus beatiei, from Mary Banning’s The Fungi of Maryland. (Photo: vintageprintable/Public Domain)

To her neighbors in 19th century Baltimore, the mycologist Mary Banning was a witch-like “toadstool lady”, known for boarding trolley cars with her arms full of slimy, putrid-smelling specimens. Many Americans once regarded mushrooms as unsightly and uniformly poisonous. Mycology—the study of fungi—was no pastime for a woman.

Though Banning would identify 23 new species and complete one of the first guides to the mushrooms of the New World, almost no one in her day knew of her discoveries, or about the striking illustrations she produced in her self-financed home laboratory.

Fungi have a long history of zealous but misunderstood enthusiasts in tight-knit scientific circles. However, Banning devoted her life to mycology at a time when women in science faced as much resistance as mushrooms did in popular cuisine. Only a few scientists were willing to listen to a self-taught, female outsider, and her work would languish in a desk drawer for almost a century before a museum curator uncovered her story.

Lexington Market in the early 20th century. Banning’s move from the rural Eastern Shore to this crowded commercial center may have inspired her to pursue botany. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

Banning came from a well-off family on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, the youngest of nine children. When her father died in 1845, her fortunes changed for the worse, and she soon became the breadwinner and caretaker for her mother and older sister, Catherine. The three women moved to Baltimore in the 1860s, near the city’s bustling Lexington Market, and Banning supported them by working as a schoolteacher.

Perhaps she took up the study of mushrooms as a respite from nursing her sick mother; perhaps, among the soot and grime of Baltimore, she missed the woods of her childhood home. Wherever the fascination began, it would last for the rest of her life and consume all her spare hours.

In the mid-1800s, botany was both a growing science and a popular amateur hobby. While men staffed university departments, a large number of amateur botanists were women. It was an ideal pastime for middle- and upper-class ladies: they could improve their health through outdoor exercise, practice their drawing skills, and celebrate the beauty of God’s creations, all of which were essential components of female virtue.

Coprinus comatus. (Photo: vintageprintable/Public Domain)

Banning could use these rationales to justify her interest in mushrooms, although the case was a bit more tenuous with rotten-smelling fungus than with blossoming roses. As a deeply religious person, she believed that mushrooms’ humble status and hidden beauty were keys to appreciating a divine spark in all creation. “Fungi are considered vegetable outcasts,” she wrote. “Like beggars by the wayside dressed in gay attire, they ask for attention but claim none.”

What began as “charity” became “a fascinating occupation”, as Banning taught herself the latest classification systems and devoured all the literature she could find on mycology. She frequented the Peabody Institute Library, whose librarian noted her “pleasant although somewhat erratic manner.” Most important was her pioneering work in the field.

She set out on a 20-year project to document the fungi of her home state, often over rough terrain. “I hire a carriage, a wagon, or any sort of vehicle I can get,” she explained. At the time there was only one published work on American fungi, so she would blaze new trails with every species she found and described.

A stereoscopic view of Druid Hill Park, in Baltimore, from the 1880s. The park was one of Banning’s favorite mushroom-hunting spots, within easy reach by streetcar. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

While most female “botanizers” sketched flowers, Banning’s quest for lowly mushrooms got her labeled a lunatic. “There is no sympathy for the work,” Banning wrote of the people she encountered in her travels, “in fact they regard it as ridiculous.” One man warned her, “you’ll poison yourself to death!” When he thought she was out of earshot, he grumbled, “Poor thing…clean gone mad!” Banning took no offense that “they regard me as a crazy woman…I pity their ignorance.”

However, as the yields of her work grew–she ultimately identified nearly two dozen new species of fungus–she felt the limitations of her amateur status and sought access to the male-dominated scientific community.

Banning reached out through the mail, where gender was less of an obstacle and her expertise could speak for itself. Charles Horton Peck, a leading mycologist with a post at New York’s State Museum, became her closest confidante. She wrote to Peck in 1879 that “you are my only friend in the debatable land of fungi and your kind instruction is valued above all measure.” Her correspondence with Peck and other mycologists contributed to the growth of the discipline in the United States, but she rarely published and never earned money or recognition. Like many female writers and scientists, her contributions happened off the record and would have remained invisible if not for the chance rediscovery of her work decades later.

Histilina hepatica Schaeff. (Photo: vintageprintable/Public Domain)

By 1888, at the age of 66, Banning had completed her manuscript on The Fungi of Maryland. With 175 lush, hand-painted watercolors plus extensive descriptions, she knew that it was “too large to be published without incurring significant expense,” and had little hope of seeing it into print. To Peck, she confided, “it is the work of nearly 20 years, begun under the greatest of difficulties, but pursued with the most untiring zeal.” In March of 1889, she mailed him the entire manuscript, deciding that the stewardship of a well-known authority offered the only chance for her work to reach the larger scientific community.

Throughout her career, Banning struggled with doubts about meeting her own exacting standards. Without a university education, she would always feel at a disadvantage. She never actually met Charles Peck, and never had formal training in the field. This was another reason that she let The Fungi of Maryland languish as a manuscript. Banning refused to publish without “being able to certify that all the plants given were rightly determined,” that is, confirmed by other experts–an impossibility since she was the only mycologist who’d seen many of the species described.

In 1894, as her health took a sharp decline, Banning wrote to Peck, “I am never too sick to take an interest in fungi and flowers. I wish I had given my whole life up to that study.” But she still didn’t feel safe expressing this regret, and backtracked. “Home duties occupied my time… I had rather die with the feeling of having done my duty than…having gratified an undying love for botany.” For a woman of her era, pure intellectual fulfillment was not a virtuous goal–it was, in Banning’s words, not “right.”

She had not led an ordinary woman’s life, though; she made time for her studies by cutting out family and friends, and she put all her savings into equipment and field research. Male scientists made those sacrifices to boost their professional status, but Banning had no hope for any reward besides the knowledge that she had advanced mycological understanding. Unfortunately, Charles Peck couldn’t give her even that assurance. After sending her manuscript, she wrote repeatedly hoping for some feedback on her work: “I would like to know if it has been of any use to you,” and again, “I wish you would tell me something about its usefulness.” No evidence of his response remains.

Lactarius indigo Schw. (Photo: vintageprintable/Public Domain)

The Fungi of Maryland sat largely forgotten in the herbarium of the Peck’s museum. In her final years, Banning was forced to find cheap lodging in a boarding house in Winchester, Virginia, surrounded by “constant jostle and upheaval”. She died there in 1903, and no obituary appeared in the Baltimore papers.

It’s a testament to the peculiar solidarity of mycologists that her work inspired others to reconstruct the fragments of her life story. Howard Kelly, one of the founding doctors of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and a mushroom enthusiast, made a pilgrimage to the State Museum in the 1910s to view Banning’s “astounding interesting volume”. He made copies of all her surviving correspondence, the source of her words quoted here.

When John Haines, a curator of mycology at the New York museum, unearthed The Fungi of Maryland again in the 1980s, it was stashed in a dusty, neglected drawer behind a case of taxidermied chickens. The vivid watercolors had somehow survived decades of neglect, and he quickly put her work on display. “I was captivated,” he wrote, “and I want more than anything to see her book printed for all.” However, Haines also failed to find a publisher for such a lavish edition.

Banning dedicated her life to mycology, but she lived in a world where women couldn’t identify first, or even second, as scientists. Her first identity was as a caretaker for her family; her second was as an educator, promoting the morally uplifting effects of nature study. Only a small circle of friends, the most important of whom she never met, understood that her third identity, as an accomplished mycologist, was her truest self.

As mushroom-hunting grows in popularity today, fans of scrutinizing fungus might also bring Banning’s hidden work back into view.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook