Inside the Most Amazing Map Library That You’ve Never Heard Of

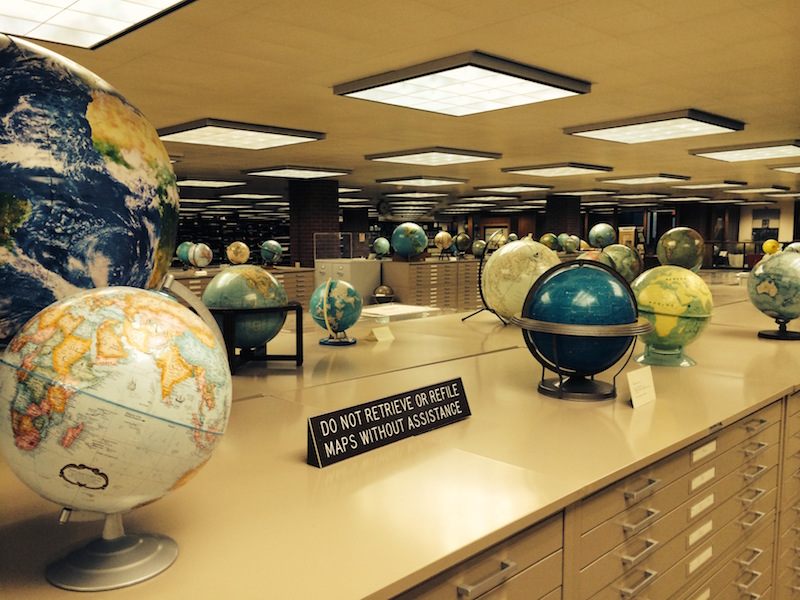

The American Geographical Society Library at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

Within the campus of University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee is a geographer’s treasure trove: over a million artifacts from the American Geographical Society, one of the most incredible collections of maps, atlases and globes to be found in America.

But, ironically, the library is practically unexplored territory. When I asked for directions on campus many students themselves didn’t know it was there.

It’s an inconspicuous home for a storied collection: this is the final resting place of the library of the illustrious American Geographical Society. Once a powerhouse of exploratory resources, the organization had fallen on hard times in the late 1970s. The private donations and corporate funding on which they had been reliant, had reduced to a trickle, and the Society was forced to sell its imposing neo-classical headquarters in Manhattan’s Washington Heights. Eventually downsizing to a small rental office in Brooklyn, the Society was adamant that its unparalleled collection should be kept intact. Resisting the temptation to sell off its valuable archive, including the remarkable signed AGS Fliers and Explorers Globe, they undertook a nationwide search for a suitable home. As current AGS President, Professor Jerry Dobson explains, “The truth is that our revenues didn’t allow us to take care of the collection in a proper manner, so we held a national competition for a suitable repository.”

Faculty members of the geography department at UWM heard what was happening and applied. The University itself was barely 20 years old, but had a brand new library building large enough to house the entire collection. The New York States Attorney office wasn’t happy that the rich cultural heritage and treasures of the Society would be leaving the State of New York, but with no other viable option to take the collection as a whole, the decision was taken to send the collection to Wisconsin in 1978.

It took 16 trucks to move the vast collection, where it lives and is actively curated today in the Golda Meir Library. Incredibly, the precious collection is publicly available.

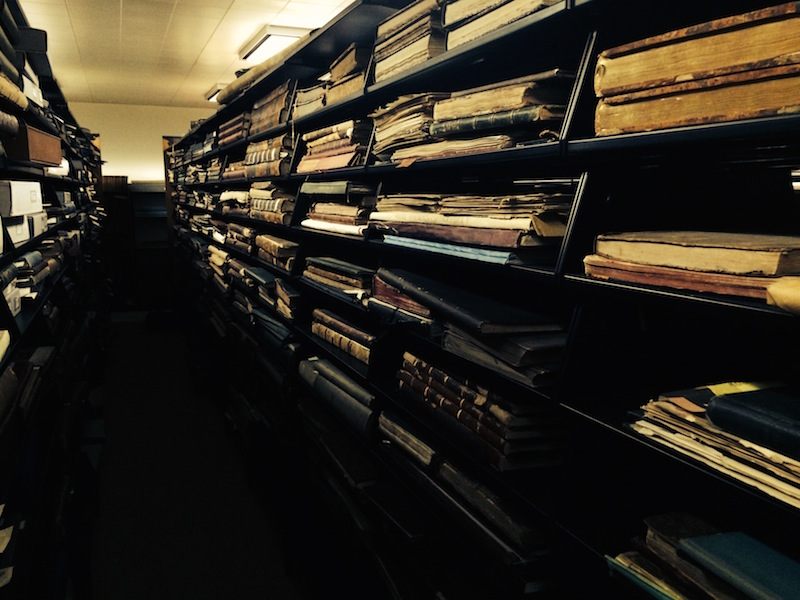

The ‘rare room’ of the Library containing some of its most valuable items. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

Entering the library, the first thing that strikes you is the amount of globes—there are hundreds of globes on permanent display, including one dating as early as 1613. The largest globe is a rare example of the giant “President’s Globe”. Made during World War II by the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS was the predecessor of the CIA), the 50 inch diameter globes were made for President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Weighing over 700 pounds, and thought to be the most detailed and accurate globes made up until that point, the intent was that FDR and Churchill would have an identical reference source as they plotted their war plans. Roosevelt kept the giant globe next to his desk in the Oval office, and it can now be found in his former home in Hyde Park. The globe on display in the AGS library was one of 12-15 originally made by Weber Costello out of Chicago. Others were constructed for the Air Force and the Office of War Information.

On the wall of the “rare room,” past shelves of vellum bound atlases from the 17th century is a map of the world with a single arched line stretching over the Atlantic. Inscribed, “used in laying out great circle course for New York to Paris flight” and initialed C.A.L., it is Charles Lindbergh’s actual hand drawn navigation map from his record flight in 1927. It was donated to the AGS by Lindbergh himself.

Photograph taken by Belmore Browne of the expedition to climb the Ruth Glacier, Alaska. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

Next to it is a series of maps depicting what we now know as New Zealand and Australia. Dated 1770, they are signed “Lieut. J. Cook, Commander of His Majesty’s Bark the Endeavour.” These are the actual maps, drawn by his own hand, from when Captain Cook explored and mapped the previously uncharted east coast of Australia. Cook was such a first class cartographer that his maps still hold up today for their accuracy.

Thrilling artifacts, for sure, but it’s hard to wonder why the collection isn’t in a major museum, getting a bigger audience. After all, the original intent of the American Geographical Society was to be a resource for exploration; it was founded to discover the lost Sir John Franklin polar expedition. Today the collection stands at roughly 500,000 maps, 200 globes and 12,000 atlases. There are over 600,000 pictures in the media collection, nitrate negatives and glass plates many of which don’t exist anywhere else. They record countless expeditions undertaken by the Society, as well as important events in world history and geographical discoveries. Rows upon rows of shelves are filled with rare travelogues from the golden age of Victorian exploration, titles such as “The Wild Tribes of the Soudan”, “The Unknown Horn of Africa” and “The Cave Dwellers of Southern Tunisia.”

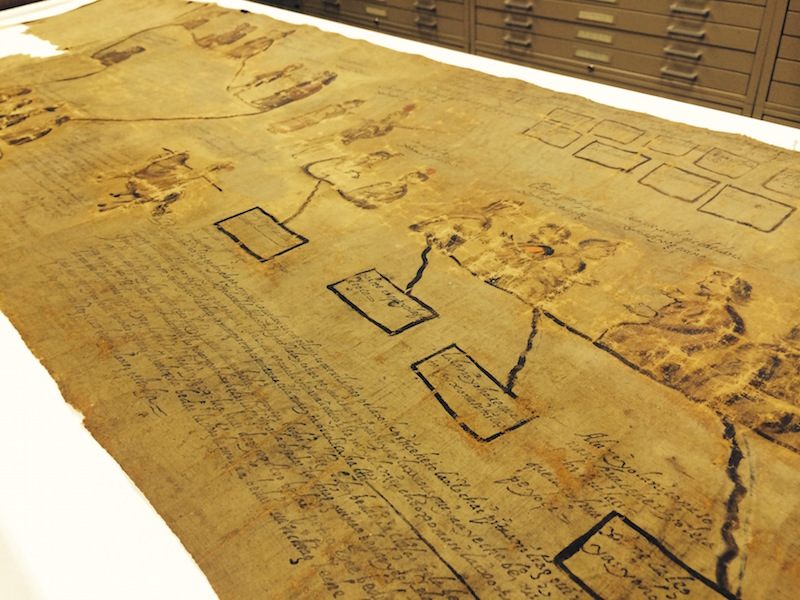

Pictorial history-map of Santa Catarina Ixtepeji, a village in Mexico. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

But the library’s acquisition of them isn’t just a historical accident. In the room housing the archives of the Society itself, the memoranda, ledgers, and accession records that detail the day to day operating documents of the Society, Robert Jaegar, Archivist, pulls out one acid free box. It contains a small parcel wrapped in string. The typed index card attached explains that this is a “notebook found on board of the Resolute of the Franklin Search expedition. Abandoned in the Arctic 1854.” The Society’s mission ended in failure, (Lord Franklin’s ship was just discovered in 2014), but it set in motion the collection of artifacts still actively ongoing today. The next box Jaegar showed me contained a letter from 1859 sent to the AGS in New York, with the return address, ‘Dr. David Livingstone, River Zambezi, Eastern Africa’, shortly before he lost contact with the outside world. The library is overflowing with similar invaluable primary source documents. Marcy Bidney, the head curator of the American Geographical Society Library explains how “it was always intended as a practical resource, hence the decision to house the collection publicly available in a library.”

For Susan Peschel, Visual Sources Librarian at the AGSL, organizing this collection has been a lifelong work. Originally interning at the old Society headquarters in Manhattan, Peschel was studying Library studies in Milwaukee when the 16-truck archive arrived in 1978. The collection was so extensive, it took two years of organizing before it opened to the public. Peschel has been curating the collection ever since; and it’s proved to be an invaluable research resource.

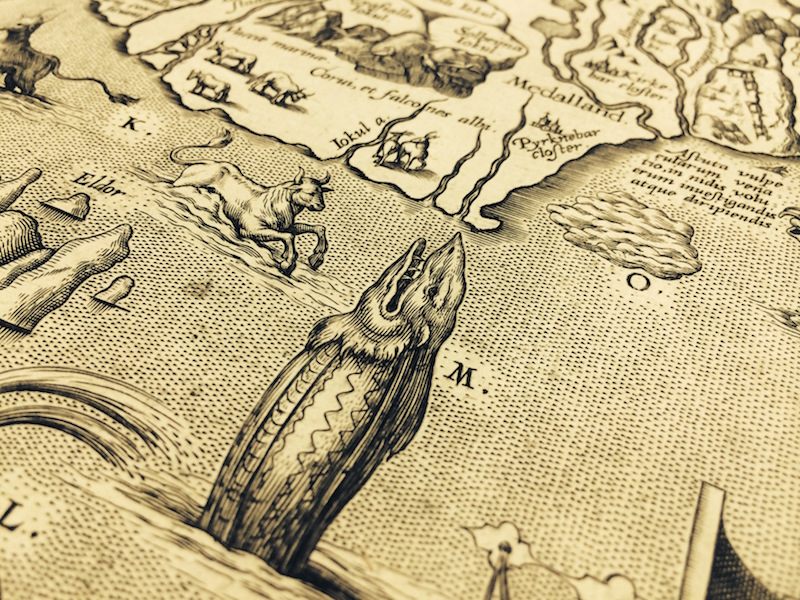

Abraham Ortelius’ 1570 map of Iceland, depicting sea monsters (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

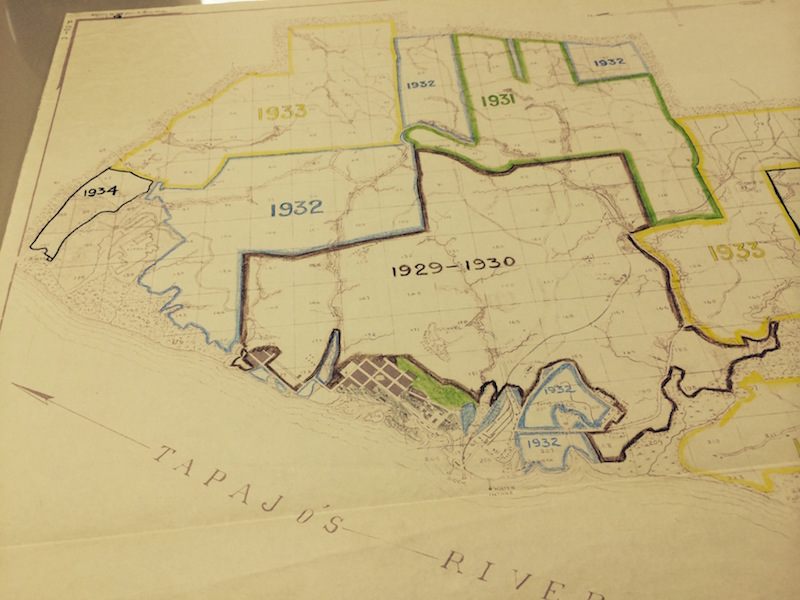

When Greg Grandin wrote his account of Henry Ford’s lost jungle utopian city Fordlandia, the library was able to pull from its archives the original hand drawn plans belonging to the Companhia Ford Industrial do Brasil. The maps not only plotted the twelve hour boat exploration down the Amazon river to the planned rubber plantation, but it laid out the entire estate, even down to the individual 71 houses for the 106 families that took part in Ford’s doomed city.

The oldest map in the collection dates from 1452. One of only three surviving MappaMundi drawn by the Venetian cartographer Giovanni Leardo, it is considered one of the finest example of Renaissance map making, and the only one to be found in America. It is an extraordinary vision of how our world was viewed at the time, with Jerusalem as the epicenter, the Mediterranean Sea running north to south, and featuring the only three known continents, Asia, Europe and Africa.

Dr. Livingstone, we presume. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

Bringing to mind the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Society Library is filled with countless shelves of forgotten atlases, secret lock boxes containing Napoleon’s beautifully illustrated “Description de l’Egypt’, and incredibly rare early editions of Ptolemy’s Cosmographia. Ptolemy had originally mapped a spherical world as early as AD 150, but the work disappeared. By the time of Leardo’s MappaMundi the world was flat again. Ptolemy’s atlas was rediscovered during the Renaissance and is a view of the world much more recognizable today. At the AGS library you can hold in your hand the physical atlas that forever changed the world’s view of itself. You can even see the impression the original copper plates left on the vellum.

Original map outlining Henry Ford’s lost jungle utopian village Fordlandia. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

“When we look at these maps it really is this history of world exploration development of knowledge about what the world looked like,” Bidney says. Flemish map maker Abraham Ortelius may have been the first person to imagine that the continents were originally joined together, but he also created some of the original “here be dragons” maps. His map of Iceland from 1603 records where to find specific aquatic monsters, ocean unicorns and sea hogs.

The Society library also holds a remarkable collection of more fanciful maps. The far end of the library, section 999, is home to “Imaginary Places, tables and charts”; here Middle Earth is actively curated as North America. One of the more chilling items in the archive, is a map of Germany from 1936. Printed in English by the Reichsbahnzentrale für den Deutschen Reiseverkehr, it was intended as a tourist advertisement and travel guide to visit “Germany, The Beautiful Travel Country”. Colorfully illustrated in a style similar to “Where’s Waldo?” it shows at its jovial best a country that was anything but.

Charles Lindbergh’s signed New York to Paris flight navigation chart, 1927. (Photo: Luke Spencer.)

Perhaps my favorite library items surround Robert Peary’s discovery of the polar island Crocker Land. In 1906, Peary had failed to reach the North Pole. Terribly short of cash and desperate to launch another attempt on the Pole, Peary claimed to have seen an undiscovered island on his expedition off the coast of Greenland. He called it Crocker Land in an attempt to appeal to one of his financial backers, George Crocker to release more funds. The expedition was green lit, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History and the AGS. In reality, Peary had made up the island entirely. Disaster struck when the expedition hit terrible weather and was stranded in the ice for four years. To avert suspicion, the expedition actually began to map and plot the fictional island to show George Crocker that his investment hadn’t been in vain. Peary had an actual map drawn up indicating the location of the island, “seen by Peary 1906.” For four years the expedition took astronomical records, studied glaciology, and terrestrial magnetism of an island that didn’t exist.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook