The Strange Victorian Computer That Generated Latin Verse

Called the Eureka, it may have influenced Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace.

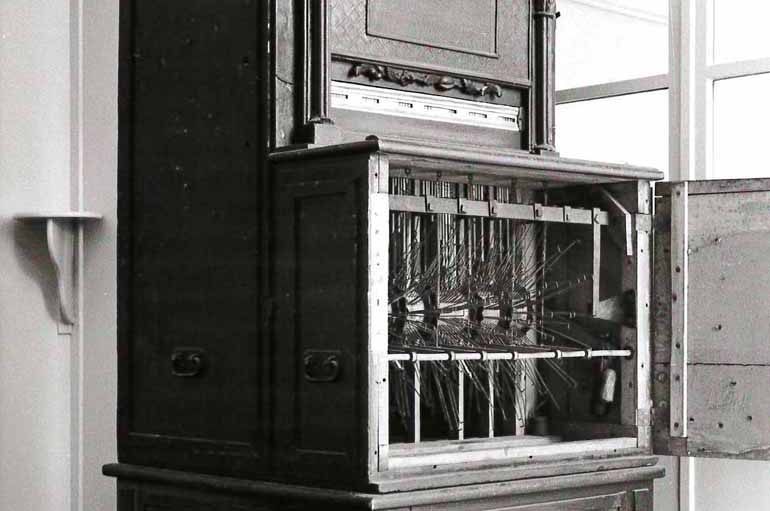

Looking inside the Eureka machine. (Photo: © Alfred Gillett Trust)

In July 1845, British curiosity-seekers headed to London’s Egyptian Hall to try out the novelty of the summer. For the price of one shilling, they could stand in front of a wooden bureau, pull a lever, and look behind a panel where six drums, bristling with metal spokes, revolved. At the end of its “grinding,” what it produced was not a numeric computation or a row of fruit symbols, but something quite different: a polished line of Latin poetry.

This strange gadget, a Victorian ancestor of the computer, was called the Eureka.

The Eureka was the brainchild, and obsession, of a man in southwest England named John Clark. The eccentric Clark was a cousin of Cyrus and James Clark, founders of the Clarks shoes empire (which went on to popularize the Desert Boot in the 1950s and is still going strong). Clark built the Eureka at a time when such devices were all the rage. As literature scholar Jason David Hall explains in an academic article on the Eureka, the machine joined other proto-computers like the Polyharmonicon, a machine that composed polkas, and the Euphonia, which “spoke” when a person played an attached keyboard.

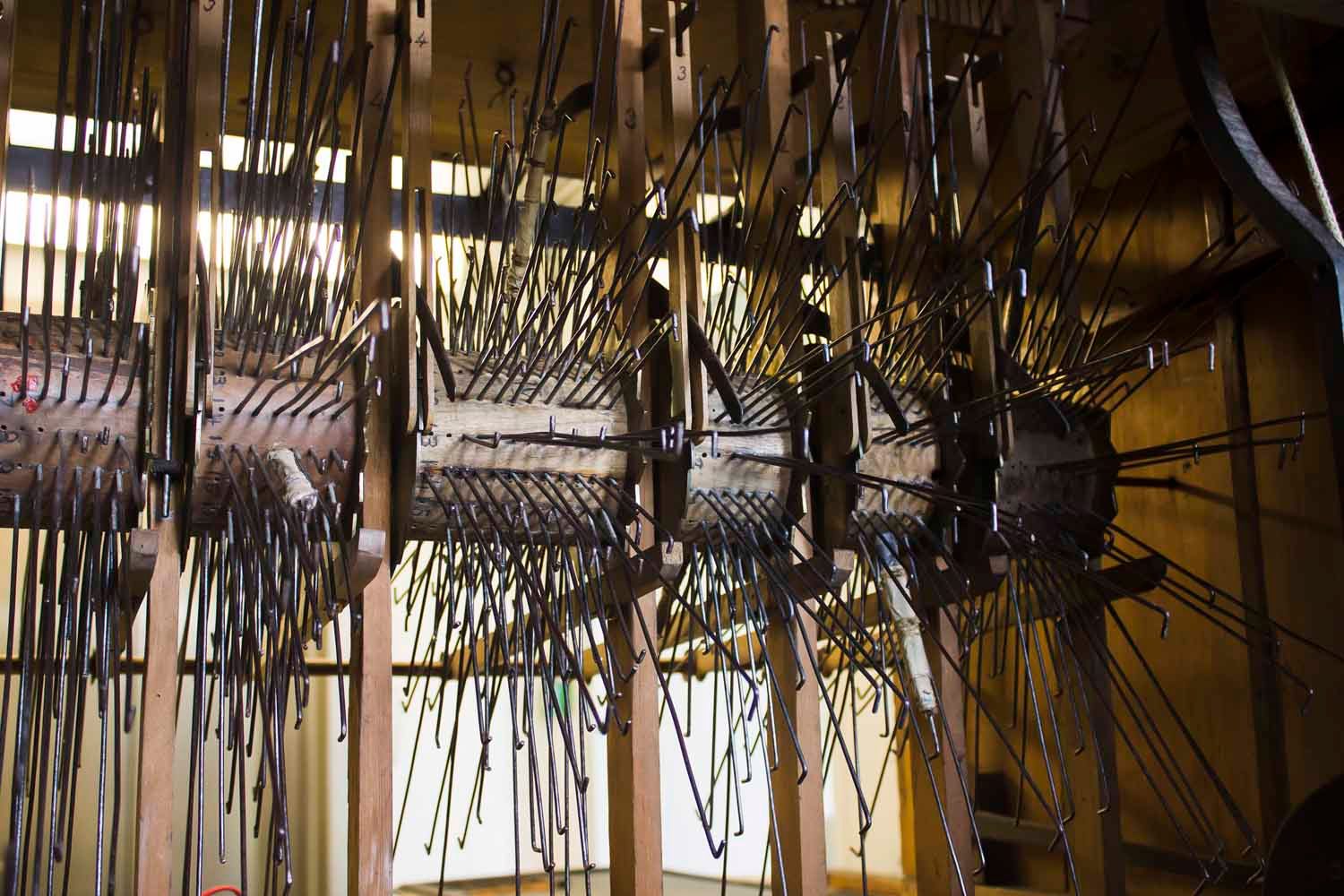

The inner workings of the Eureka machine, with wooden drums and metal spokes. It can run through 26 million variations. (Photo: © Alfred Gillett Trust)

But a Latin hexameter verse—that was something else. The hexameter is the meter of ancient epic, of the poets Ovid and Virgil. Each line has six metrical units called feet. A foot can be either a spondee—two long syllables—or a dactyl, a long syllable followed by two short ones. However, the fifth foot of the line is almost always a dactyl, and the sixth is usually a spondee. So there are strict rules for writing poetry in Latin hexameter that make it akin to following a mathematical formula.

_ ͜ ͜ | _ ͜ ͜ | _ _ | _ _ | _ ͜ ͜ | _ _

To ensure that the Eureka’s lines of automatic poetry not only scanned metrically, but made sense, Clark gave the words on each of the drums similar meanings, and had them obey the same syntactical order each time:

Adjective - Noun - Adverb - Verb - Noun - Adjective

_ ͜ ͜ | _ ͜ ͜ | _ _ | _ _ | _ ͜ ͜ | _ ͜

Martia castra foris praenarrant proelia multa.

“Military camps foretell many battles abroad.”

The number of possible permutations the Eureka can run through is a dizzying 26 million. “If we had it running continuously, it would take 74 years for it to do its full tour before it started repeating itself,” says Karina Virahsawmy, a curator at the Alfred Gillett Trust, the nonprofit that preserves the history of the Clark family and their company. “Every time I think about it, I’m still mind-boggled as to how somebody did that in the early 19th century.”

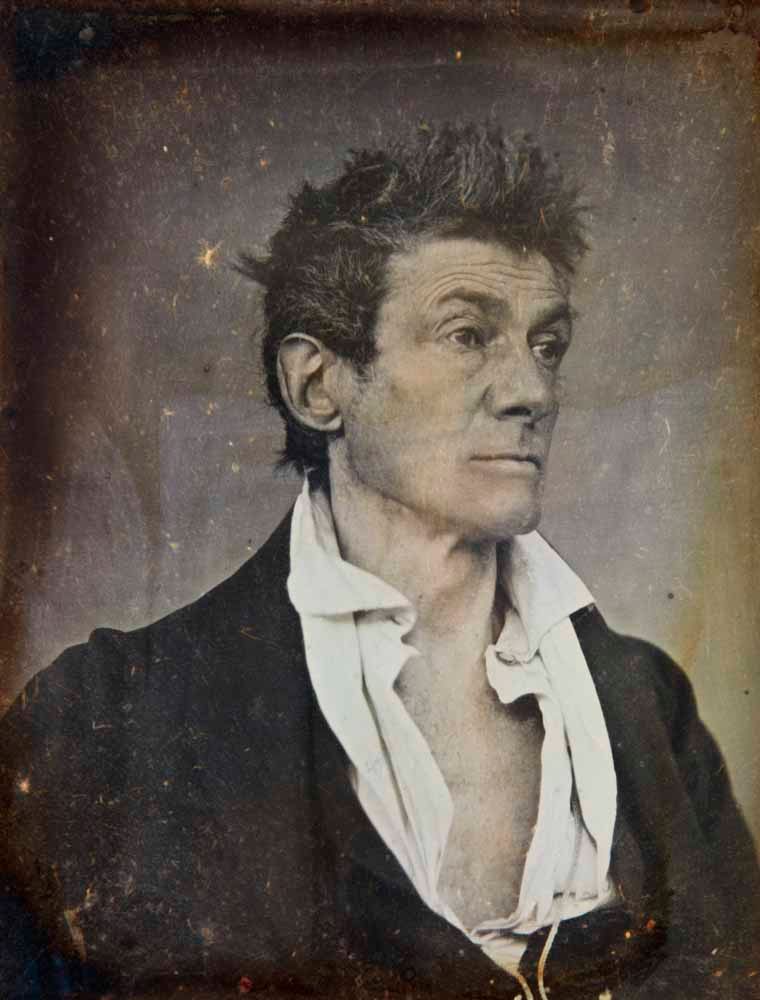

The Eureka was one of the forerunners of the programmable computer, invented by Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace. “From what we’ve seen and researched, Babbage would have gone to the exhibition,” Virahsawmy says. “There’s a possibility [Clark and Babbage] would have known each other.” Babbage once described Clark as being “as great a curiosity as his machine,” possibly due to his odd manner of dress: he was fond of wearing a wide-open shirt and a neckerchief.

Daguerreotype of John Clark from the 1840s or early 1850s. (Photo: © Alfred Gillett Trust)

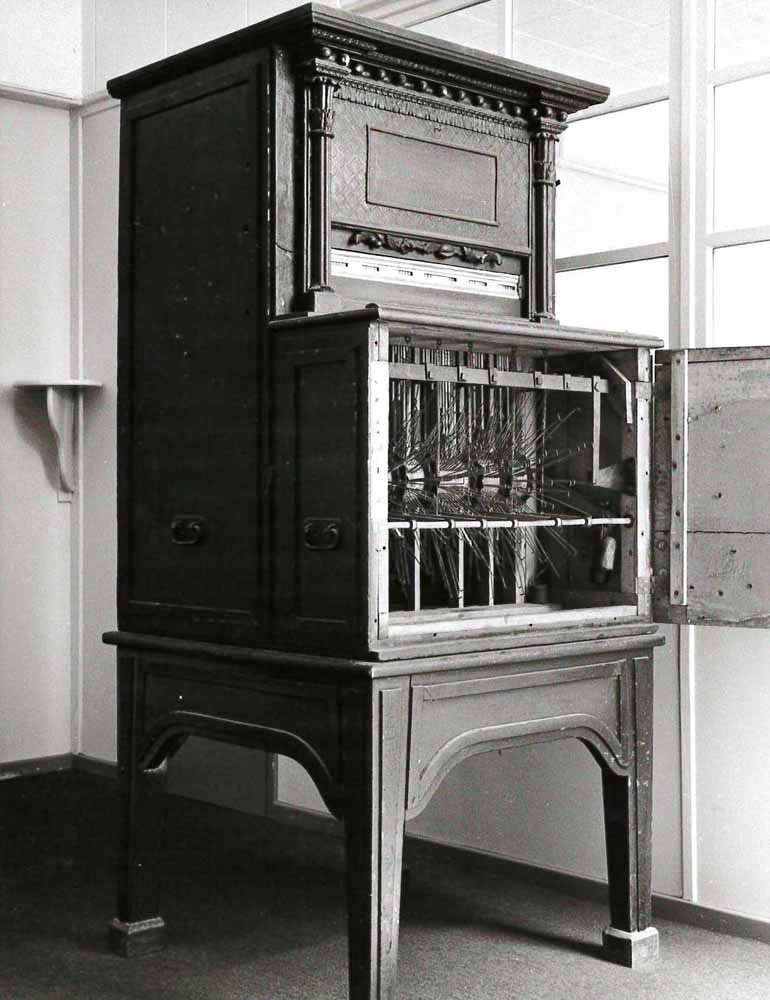

The exhibition of the Eureka was successful enough that Clark retired on the proceeds. After he died in 1853, the machine ended up in the family shoe factory in Street, Somerset. It is now in the holdings of the Trust, where for years it sat gathering dust in a storeroom.

With a grant from the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council, however, the Trust and a team of conservators and scholars (including Hall) just restored the Eureka to working order, and they are now creating a full-scale modern replica of it. The team also plans to use 3D scans to make an interactive virtual replica that can be used online. The whole process will be chronicled in a short documentary film scheduled for release in early 2017.

The question remains, though: why Latin verse? The Greek and Roman classics were central to elite education in Victorian England, especially prosody (the study of metrical verse). When it originally went on display in the 1840s, the Eureka tapped into debates about education then swirling. Reformers wanted to dethrone the classics and broaden curricula to include subjects like chemistry and modern history. Whether a Victorian saw the Eureka as a celebration or a parody of classical education may have depended on his or her stance on reform.

The Eureka before conservation work, around 1970. (Photo: © Alfred Gillett Trust)

Some Victorian observers were discomfited by the notion of a machine writing poetry, a challenge to human creativity if ever there was one. The controversy over artificial intelligence has only intensified since then. Maybe that’s why a device so seemingly esoteric still captures people’s interest.

Earlier this month, shortly after the restored Eureka returned to Somerset from the University of Exeter, the Trust exhibited it for a few days, ran some demonstrations, and got “great numbers” of visitors, Virahsawmy says. “It was very much eye-opening and awe-inspiring when people came in,” she says. After 170 years, this singular device is still mirabile visu (“marvelous to behold”), to quote one of Virgil’s immortal hexameters.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook