The Unsolved Case of the Attempted Assassination of Pope John Paul II

The site of the 1981 Pope John Paul II assassination attempt (Photo: Public Domain)

It was late afternoon on May 13th 1981 when Pope John Paul II emerged from St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, ready for his weekly audience in the square. Thousands were waiting for a glimpse, a photo or perhaps even a touch from the adored spiritual leader of the Catholic Church. At about 4:50 p.m., the Pope stepped into the white open jeep specifically made for him, known as the “Popemobile,” and rode around the elliptical-shaped plaza, weaving through the festive crowd.

At approximately 5:19 p.m., the jeep stopped on the southwest side of the Basilica steps. Hands, cameras and crosses extended from the crowd. So did a gun. Shots rang out. In an instant, Pope John Paul II clutched his chest and slumped into the arms of his aids as a bright red stain slowly extended across his white cassock. Pope John Paul II had been shot.

The shooter, Mehmet Ali Agca, was immediately seized at the scene as he attempted to flee the square. According to official reports, he kept repeating to police that he “couldn’t care less about life.” They also found a letter in his pocket that read, “I, Agca, have killed the Pope so that the world may know of the thousands of victims of imperialism.” Fortunately, Agca’s prewritten note was incorrect. Ultimately, he was not able to assassinate the Pope.

34 years later, Agca’s exact motives or who put him up to it are still unknown. The 1981 attempted assassination of the Pope remains clouded in mystery and conspiracy.

Details about Mehmet Ali Agca’s early life are murky. He was born in 1958 in the Malatya province of central Turkey, about 200 miles from the Syrian border. Throughout his youth, he was known as a petty criminal and was likely also a heroin smuggler between Turkey and Bulgaria. Sometime in the mid to late 1970s, Agca reportedly became a member of the Grey Wolves, a Turkish neo-fascist nationalistic terrorist organization that may have relied on the financial backing of the Turkish mafia.

Their mission was to unite all Turkish people into a greater, more powerful Turkey… “from the Balkans to Central Asia.” The Grey Wolves were willing to accomplish this through violence and assassinations. According to the BBC, at some point, Agca moved to Syria at the behest of the Grey Wolves, where he was trained to be a terrorist.

The Fiat Popemobile in which Pope John Paul II was the subject of an assassination attempt. This vehicle is now in the “Carriage museum” of the Vatican City. (Photo: Jebulon/CC0)

Shooting the Pope was not Agca’s first foray into murder. In 1979, Agca was convicted and jailed for the high-profile assassination of prominent newspaper editor Abdi Ipekci. In the months prior to his murder in February 1979, Ipekci wrote articles exposing Turkey’s far-right groups. Reports suggest that Grey Wolves’ leader Abdullah Çatlı, upset with the bad press, sent Agca to do the deed.

When Agca was caught, convicted and jailed for the murder, he did not serve his whole sentence. He escaped from the high-security prison by wearing a private’s uniform and simply walking out, instigating the theory that he had help from high-level people. Shortly after the breakout, the Turkish paper Milliyet published a written threat that Agca had sent them, which read that the Pope was an “agent of Russian and U.S. imperialism”. The fugitive vowed to kill him.

After escaping from prison, Agca roamed around the Mediterranean and the Balkans, assuming different identities and carrying out underground missions for the Grey Wolves. Despite being wanted and Interpol distributing his picture around the world, he avoided arrest. During this time, he was again suspected of another murder- this time of a grocer and disloyal former member of another Turkish terrorist group. Prosecutors were unable to press charges, though.

Agca arrived in Rome a few days prior to May 13th, 1981, perhaps with long-time acquaintance Oral Çelik. An Italian judge would later claim that Çelik had helped Agca carry out the attack, promoting the theory that the assassination attempt on the Pope was a much larger conspiracy.

What isn’t disputed, though, is that Agca arrived at St. Peter’s Square, and immersed himself in the crowd. Just as the Pope stopped to touch the hands of the public, he opened fire.

Two photographs tell the tale of the horrific scene. The first one shows the Pope reaching out into the crowd as hands and cameras push forward. On the far right side of the picture is a hand clutching a gun, pointed directly at the Pope. No one but the camera notices. The second image, undoubtedly taken a few moments later, shows the Pope slumped into the hands of his aids. People are crying and screaming in the background as his aid struggles to hold the Pope up.

The site of the shooting is marked by a small marble tablet bearing John Paul’s personal coat of arms and the date in Roman numerals. (Photo: Public Domain)

It was determined that four bullets struck the Pope (though sources vary), two in his abdomen and two in his left arm and hand. Two other bullets had gone into the crowd and injured two women, both of who would eventually recover. The Pope was rushed to the hospital and immediately went into surgery. Before being put under by anesthesia, a nurse quoted the Pope as saying “How could they have done this?”

The surgery lasted about five-and-a-half hours, and surgeons were able to remove at least one of the bullets. Later, the doctors would say that the Pope was very lucky. While the injuries were serious, the bullets had missed vital organs and blood vessels. They would announce before the night was over that they were very hopeful that “the Pope will recover and stay with us.”

Four days after the attempt on his life, the Pope made a public statement forgiving Agca and asking the world to pray for him.

Despite Agca’s affiliations and the handwritten note, there was no immediate agreement on why or who told him to shot the Pope. Agca certainly didn’t help the matter by constantly contradicting his own claims. At first, he said he acted by himself. Then, he claimed he was “the Messiah” and “Jesus reincarnated.” At some point, he said the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) put him up to it. He also perpetuated the “Bulgarian Connection theory” that the Bulgarian secret service, working in cahoots with the Soviet KGB, had paid him to shoot the Pope. At one point, he even said he wanted to kill the King of England, but when he realized England only had a Queen he decided not to do it because “I am Turkish and a Moslem and I don’t kill women.”

Detectives begun to believe that he was being coached and was making was making contradictory claims to throw investigators off the scent of his exact motives, whatever they were. The Italian press started “making confident assertions” that Agca’s attempt on the Pope’s life was part of a larger international conspiracy. Despite this, Italian authorities continued to maintain that there was no evidence to support that claim.

Agca’s trial began in Italy on July 20th, 1981, a little over two months after the incident. Two days later, he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. The short trial was proof to some of a true conspiracy that went beyond one man or even a small Turkish neo-fascist terrorist organization.

Lenin Shipyard gate during the 1980 strike in Poland, decorated with a photograph of Pope John Paul II. (Photo: Zygmunt Błażek/CC BY-SA 3.0 pl)

Many wondered which powerful organizations or countries might have a genuine grievance with the pope. The Soviets, for one, could not have been pleased with Karol Józef Wojtyła’s rise to the papacy in 1979. He was known throughout the world as pro-labor and anti-communist. When he made his first trip to his homeland of Poland as Pope John Paul II in June 1979 there was little doubt what was his intention was – to help undermine Communism. Upon his arrival and the mass excitement that accompanied it, it became clear to Pope John Paul II, according to his biographer George Weigel, that “Poland was not a communist country; Poland was a Catholic nation saddled with a communist state.”

All of this worried the Kremlin; to the point that it was not implausible to some that they would carry out a plan to assassinate the Pope. They had resorted to this type of tactic before in order to squash perceived threats to their regime. 25 years after the attempt on the Pope’s life, an independent Italian commission backed up this very claim.

In 2006, that Italian commission released a report that concluded that, “beyond all reasonable doubt… the leaders of the USSR took the initiative to eliminate the Pope.” According to the report, the Soviets believed the Pope’s support of the democratic Solidarity Labor Movement in Poland was a threat to the USSR’s hold on the country. The report also detailed how the KGB planted bugs and moles in the Vatican. To many, this was proof of the “Bulgarian Connection theory” – that the Soviets had asked the Bulgarian Secret Service to find someone to shot the Pope. Knowing his past, they choose Agca and paid him handsomely. Still, American historians and former CIA ops have claimed the report is based on false information and they firmly believe that Agca’s actions were not part of a greater conspiracy. Others credit the Turkish “deep state.” To this day, no one can agree on the truth behind why Agca shot the Pope.

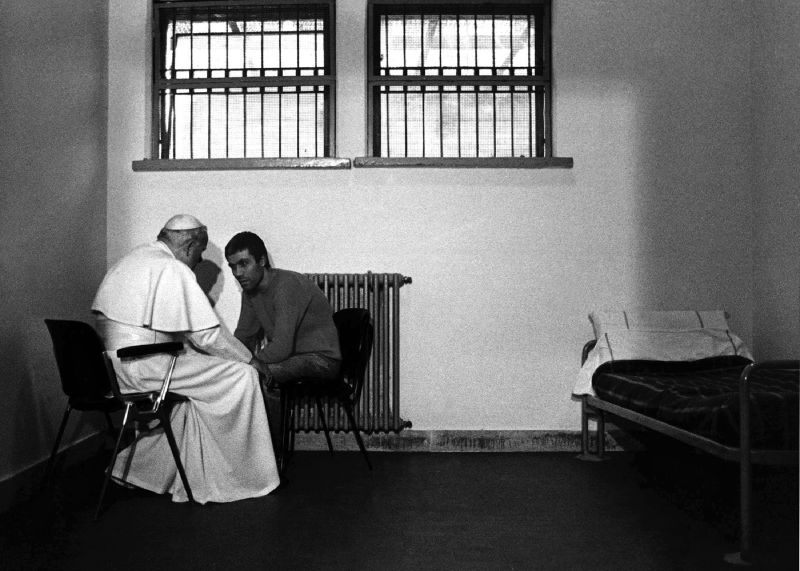

Pope John Paul II meeting with Mehmet Ali Agca in his jail cell in Rome. (Photo: Flickr CC)

In December of 1983, Pope John Paul II visited Agca in his prison cell and forgave him. This meeting was immortalized on the cover of Time Magazine. Thanks to this meeting and a clemency granted by Italy’s President, Agca was released from prison in 2010. In December of 2014, when St. Peters Square was full of holiday pilgrims, Agca showed up to the Vatican to lay flowers at the grave of Pope John Paul II, who had died in 2005.

After passing through metal detectors and placing a bouquet of white roses at the tomb, Agca was detained for illegally entering Italy. Bizarrely, he also requested an audience with the current Pope, Pope Francis, to which the Vatican spokesmen replied, “He has put his flowers on John Paul’s tomb; I think that is enough.”

After this incident, Mehmet Ali Agca was sent back to Turkey, where he lives today, presumably in hiding. He hasn’t commented on his motives or the circumstances around his attack in years. To this day, the bizarre mystery of who backed the would-be murderer of Pope John Paul II 34 years ago has yet to be solved.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook