The Voder, the First Machine to Create Human Speech

It spoke like a creepy demon.

Today, machine-made voices talk to us all the time. They act as personal assistants for our cell phones, manage our smart homes, and, occasionally, call from unrecognizable phone numbers to tell us we are final contenders in big-money sweepstakes.

Electronic voices may be commonplace now, but the road to speech synthesis is littered with the remains of devices that promised to bring us the voice of the future—but didn’t last beyond their novelty value.

One of the most fascinating relics of this quest for electric speech is Bell Labs’ Voder, the first device to bring us wholly synthetic speech. Even if it sounded like a robot demon.

The Voder, which debuted in the 1930s, was the creation of acoustic visionary and Bell Labs inventor Homer Dudley. In the late 1920s, Dudley had created the much more well-known “channel” vocoder, which coded human speech across telephone lines by turning incoming speech into electronic signals, then replicated it on the other end using electric sounds meant to mimic a person’s voice.

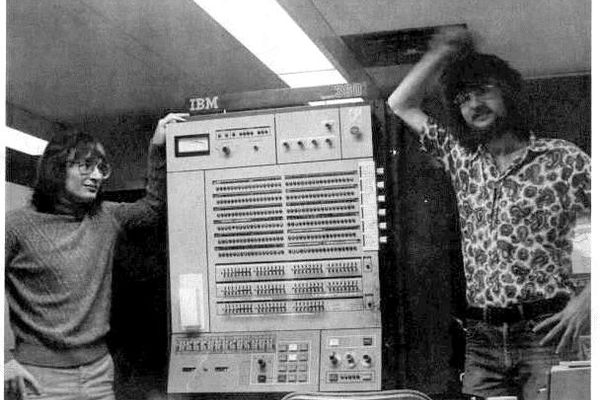

The Voder went one step further: it produced speech without the input of the human voice. Operators played it like a futuristic organ, but instead of creating music, it created talk. As a feature article in the Smithsonian’s Science News Letter from January 1939 described it, the Voder was the “first device that actually creates human speech.”

The wonder expressed in the article is tempered a little by future shock. “[The authors] slip between personifying it and calling it an ‘it.’ So there’s definitely an anxiety about whether there’s a human intelligence here,” says Lilia Kilburn, an MIT anthropologist who studies interactions between people and sonic technologies, and who has researched the cultural significance of the Voder and numerous other voice synthesis machines. “It’s interesting to hear how technologies like Amazon’s Echo are discussed with the same strange cocktail of fear and reverence now.”

The Voder was a beast to operate. The machine could create 20 or so different electric buzzes and chirps, which the operator would manipulate using 10 keys, a wrist plate, and a pedal. The spectrum of buzzes and hisses could be orchestrated to mimic speech using the 10 keys to play a range of sounds, which could switch between voiced (anything that uses the vocal cords, like “uuuuh”) and unvoiced sounds (sounds that don’t use the vocal cords, like “sssss”) with a click of the wrist bar, while the pedal would affect the pitch of the “voice,” which could create a range of inflections.

Creating words with the Voder required thinking about the various sounds that combine to create a single word, and the subtle changes that affect its meaning. It was a difficult and unnatural process, and only between 20-30 people ever even learned how to use it.

As Kilburn says, like the vocoder, and many other early speech synthesis technologies, the voice produced by the Voder was most often meant to be male, but the device was primarily operated by female phone operators. In fact, according to that same 1939 Science News Letter, Riesz and the other engineers had named the Voder, “Pedro,” after Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro, who was said to have listened to a telephone and exclaimed, “My God! It talks!”

All difficulty aside, when the Voder was finally unveiled at Bell Labs during the 1939 New York World’s Fair (the same world’s fair that featured Elektro, The Smoking Robot), it certainly seemed like something straight out of the future. For the first time, a robot was speaking all on its own. Or that’s how the presenters spoke about it.

The device was demonstrated by Mrs. Helen Harper, who was the central operator of the Voder and trained all of the other users. In an audio recording of a demonstration of the machine, Harper says that it took her around a year to learn how to operate it herself.

Harper was seated behind a sleek console, with a towering art deco image of a shouting man emblazoned on the wall behind her. While Harper ran the Voder keys, a presenter would walk people through the Voder’s vocal capabilities. During the presentation, Harper made the Voder say the same sentence in a number of different inflections, utter a phrase in French, imitate the wobbly effect of an elderly person’s voice, and even do an impression of a cow.

The Voder’s speech came out a little hard to understand, and even a bit unsettling. According to Kilburn, even more than the voice itself, the concept of a talking machine must have seemed somewhat uncanny. “That’s so spooky to people,” says Kilburn. “We speak automatically, but we don’t like to think that something can speak automatically for us.”

The Voder was shown again during San Francisco’s Golden Gate International Exposition in late 1939, but after that, the machine disappeared almost instantly. The machine was never meant as a commercial product but rather as a sort of proof-of-concept showcasing the astounding work taking place at Bell Labs at the time.

Nonetheless, Pedro the Voder can still be remembered as a fascinating glimpse at the roots behind vocal synthesis technology that we take for granted today in technologies such as Siri—not to mention the last time anyone attempted to play the human voice like a piano.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook