And Now, a Weather Report From Mars

Scientists in Spain are bringing Martian meteorology to the Earth-bound masses.

NASA’s rover Curiosity is still alive and well in the Gale Crater, just south of Mars’ equator. Meanwhile, on Earth, the team of scientists who designed the robot’s weather station, known as the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS), have decided to become the world’s first Martian weathermen.

Jorge Pla-García, the group’s meteorologist, likes the term. “When we send a human to Mars, we could include a section in the news,” he says.

Pla-García works at the Spanish National Center of Astrobiology, which is associated with NASA. Now, along with other two researchers, he has decided to publish a periodical weather report in layman terms. The other two weathermen are Antonio Molina, who inputs geological data, and Javier Gómez Elvira, who processes the data for mainstream consumption.

To make the weather report more appealing to the general public, the team has made a point of including comparisons with Earthly weather phenomena. In their first report, released on March 15, they compared the Gale Crater winds with the Chinook air streams in the Rocky Mountains of North America. Their second report, released on July 11, discusses the strong whirlwinds known as Dust Devils.

“We do it because it’s the public’s right,” says Pla-García. “They fund us with their taxes, so they deserve to know what their money is being spent on!”

In their second report, the team highlights the start of summer in the Gale Crater. It’s also the end of the dusty season in the Martian southern hemisphere. During the spring, solar radiation warmed the air closer to the ground and lifted the particles, but now it’s “crystal clear time,” says Pla-García.

This month, as in the one before, atmospheric pressure is on its way down. It’s a typical feature of the Red Planet’s summertime, as the atmosphere’s main gas, carbon dioxide, progressively freezes over the Southern Polar Cap.As usual, Martian temperatures have stayed under 0ºC for the whole month, and they shouldn’t be expected to get higher any time soon.

The Red Planet is colder than people think. A few years ago, NASA reported temperatures up to 30ºC (86 ºF) at the planet’s equator. However, according to the REMS team, that was an instrumental error the American agency hasn’t corrected. “It was taken by an engineering thermometer used to control a camera,” says Pla-García. “It wasn’t in contact with the environment. The actual maximum we’ve ever registered is 3ºC (37.4 ºF), and 99 percent of the time, it’s below 0ºC.”

The process of compiling the Martian weather report starts with the data the team downloads from REMS’ sensors. It’s data anyone can access through an app (available on Google Play and Apple App Store), but that doesn’t make the reports useless. With the app, you can see the conditions on the Gale Crater. With the reports, though, you get to understand Martian weather more broadly.

“We can get a lot of information from REMS, but that doesn’t really tell us the whole story,” says Pla-García. “We need a network of stations. That’s our problem, and that’s why we insist NASA to send more sensors to other areas of the planet. We need the context.”

To cover for the lack of stations, they use a computer model designed by American professor Scot Rafkin, who is the Assistant Director of the Planetary Atmospheres and Surfaces Department of Space Studies at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. The team simulates what’s going on in and around the Gale Crater. They compare the model and REMS’ real information to make sure the model is accurate. And it is, so they assume it’s also right for the context.

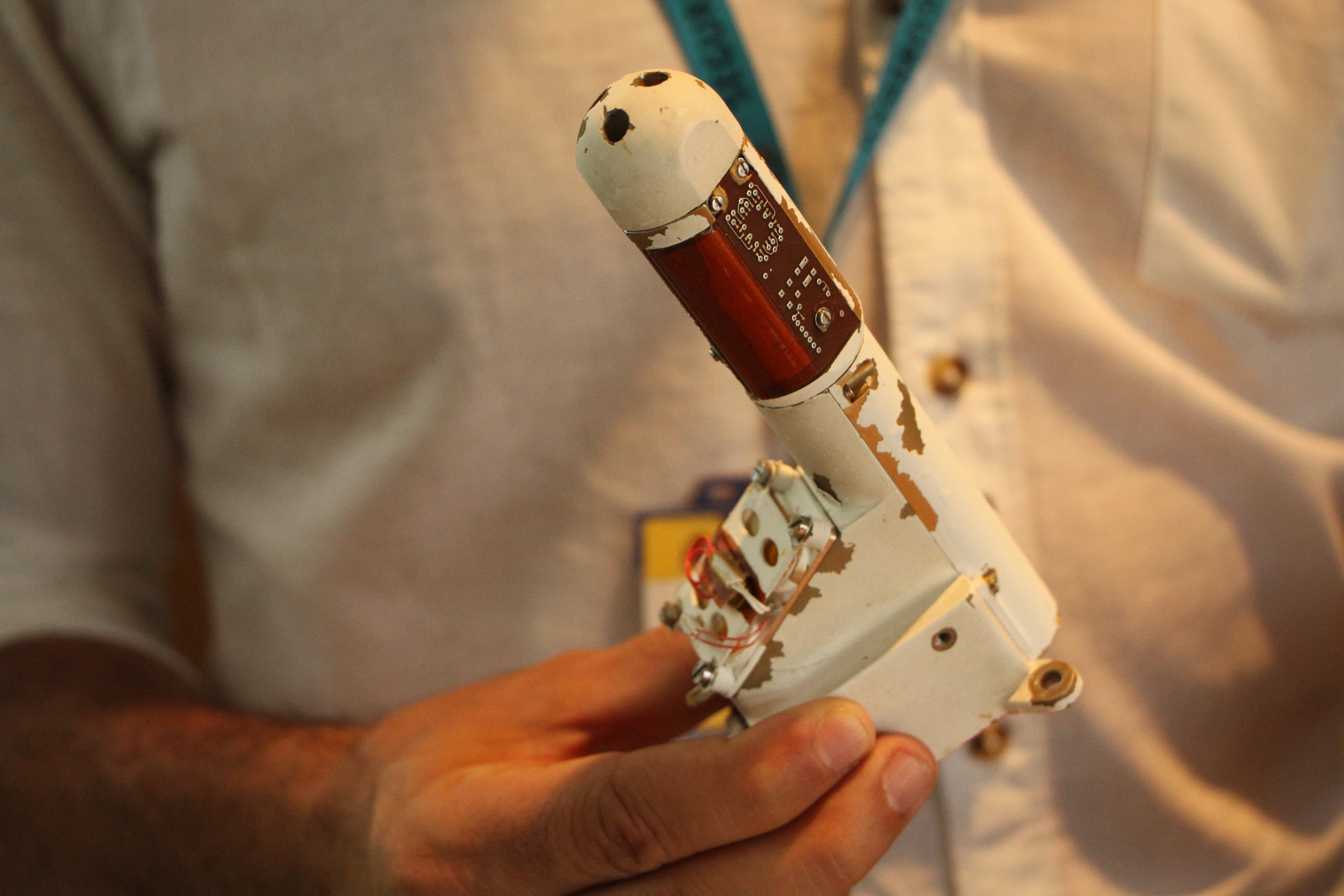

“Hey! I’m here to get the dildo!” shouts Pla-García merrily, as he enters one of the engineering labs. The device (which is indeed quite phallic) is a replica the team used to test-drive REMS before the real one went roaming on Mars. It measures UV radiation, pressure and wind speed. The one in Mars also has sensors to collect ground and air temperatures.

The 12 members on Jorge’s team take turns to keep watch, making sure the device’s abilities are squeezed to the maximum before it inevitably dies off. Pla-García says it gives him goosebumps to think he’s operating a device in another planet, but that collecting data is the hardest, most daunting part of his job.

“We used to be on watch on Martian time,” says Pla-García. “And a Martian day is 24 hours and 39 minutes long, so our work schedule was different every day. That included weekends, New Year’s Eve, Thanksgiving, you name it.”

Fortunately for them, they’re now on a more steady Pacific Time schedule.

While Jorge leaves the military base where the Center is located, he explains the point of it all. His team is trying to answer the million-dollar questions: How did life on Earth begin, and is there life out there? And he’s excited about the future.

The weather conditions in Mars are so inhospitable that the team, which has a lab devoted to researching extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—is skeptical about finding any signs of life on its surface. Solar radiation and perchlorate compounds don’t even allow for fossils, if there was any to be found.

But underground the conditions are better. The next European Space Agency rover, ExoMars 2020 is expected to incorporate a two-meter-deep drill. “I pray every day so it gets there soon and everything works well,” says Pla-Garcia. “We may have some big news then.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook