What Does it Take to Become Best in Show?

A Standard Poodle sneaking in a little beauty rest before her turn at the National Dog Show Presented by Purina. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

Dog shows—and dogs—have fascinated audiences since they began in the 19th century. The pomp, the circumstance, the Komondor, the Chinese Crested. These shows have been around for a long time; the iconic Westminster Dog Show has taken place in New York City since 1877 and been on television since 1948. And it’s not the only one airing on prime time—a Skye Terrier named Charlie recently claimed the top title at the National Dog Show Presented by Purina broadcast at noon on Thanksgiving day.

How seriously people take this hobby, of course, varies. You could end up traveling every single weekend, attending 100 shows a year, and spending six figures, or you and your pooch might just stop by a show every once in a while. Kids can even try their hand at junior showmanship competitions. Some inside showmanship tips include using cornstarch (can make a coat extra white); carrying a blow-dryer (always fluffs things up); and purchasing small scissors (whiskers should always be well-trimmed). It’s all a matter of how much spare time and money you’re willing to spend on putting a “ch.” (for champion) in front of your dog’s name, while dreaming of the ultimate glory: best in show.

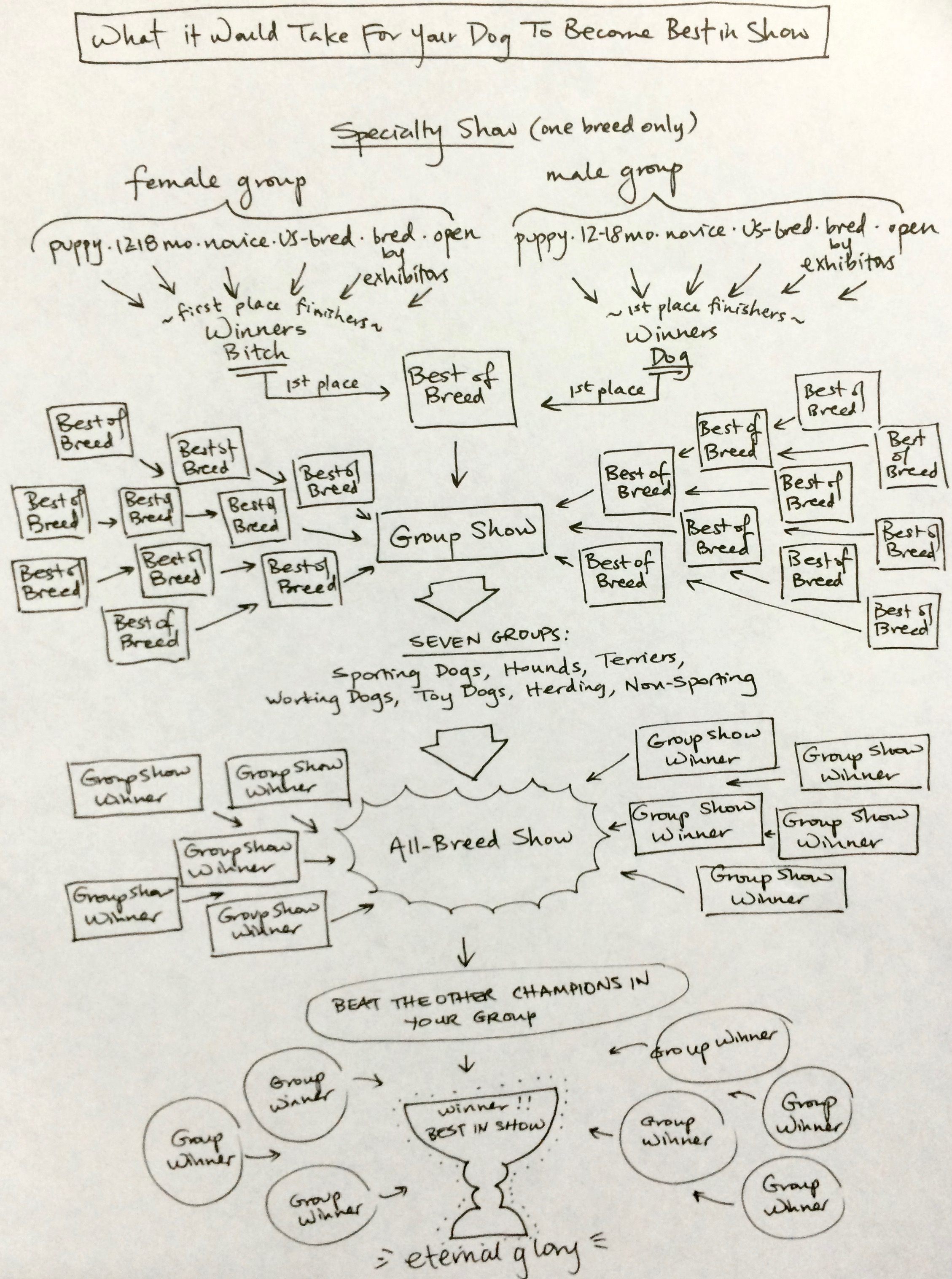

It’s a long, long road to best in show—a title often associated with the 2000 movie. Here’s a chart to give you a sense of how many other dogs your dog needs to edge out in order to claim the most hallowed title known to canine:

Yeah—right?! (Photo: Tao Tao Holmes/Atlas Obscura)

Within specialty shows (which feature only one breed) and group shows (which each feature one group), judging is based on each breed’s “Standard,” which specifies the dog’s desired attributes, including gait, attitude, and physical characteristics (size, muzzle, coat, etc). The Standard is based on the dog’s original function—so while we no longer see poodles hunting duck and game, their Official Standard may reflect that they once did.

But how exactly does the judging work? David Frei, longtime dog owner, expert, breeder, handler, commentator, and judge has hosted the Westminster Dog Show for 26 years. He’s also founder and president of Angel on a Leash, a charity organization that runs therapy dog programs across the country. Owner now of a Brittany and a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Frei helped provide us with a little glimpse into the world that is now his life.

How did your life become so dedicated to dogs?

You know, I never had a dog really, as a child growing up. And I got my first dog, which is amazing considering how huge a part of my life it is now—it is my life, it’s not just a part of my life—but I got my first dog in college, when I was living in my own house. My girlfriend said let’s get a dog and I said, Oh, okay… Guys will do anything for women. And I said, What kind? And she said, How about an Afghan Hound? And I said, What the hell is that? And we got the dog, and three weeks later, the girl left, and the dog stayed, and it was the best thing that could have happened to all of us.

An Afghan Hound prancing forward with its eyes on the prize. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

I got somewhat involved in Afghan Hounds. When you have a dog that stands out a little bit like that, people say, jeez, I know someone who’s got an Afghan Hound or my friend has an Afghan Hound. And eventually you meet, as we call them, Afghan Hound people—insert any breed name there—and eventually I met some people involved in showing dogs, and they got me dabbling into the show world, where I met my wife, now my ex-wife Sandy, who was very involved with Afghan Hounds. We got married and continued what had been her longtime family involvement with Afghan Hounds.

We took it to a certain level of success with one dog in particular, Zoomi—Stormhill’s Who’s Zoomin’ Who—named after the Aretha Franklin song. We had lots of dogs and showed lots of dogs and finished lots of champions, but Zoomi had a year where she was the top Afghan in the country, and eventually retired as top-winning female in the history of the breed. So we were very active and very visible with her, and that’s when the Westminster people found me and said that they’d heard in a previous life I had worked for the Denver Broncos and San Franciso 49ers in PR capacities. And they’d heard that and were looking for someone to do the dog show on television. They asked me if I would be interested and I said sure.

So I went back and did an audition tape and they hired me. My first show for Westminster was 1990 and this will be my 27th year, this February. So it’s amazing how that started to change my life. But I was still showing dogs, still involved with dogs, started to judge, and some other things. Dogs became my life.

A Norwegian Buhund and his junior handler. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

How does someone become qualified to become a dog show judge?

It’s a process that’s controlled by the American Kennel Club, and they have a number of requirements that change from time to time over the years. Basically, you start by judging your own breed, the breed you’ve been involved in—I started with Afghan Hounds and only judged Afghan Hounds for a lot of years. Some people start with their own breed and quickly progress, and add breeds to their repertoire, maybe they’ll add some breeds in their same group, and eventually try to get the entire group so they can also judge the group, then they can eventually judge Best in Show and many more breeds. I only judge the breeds that I have. That’s what best for me; that’s what keeps me busy. Five or six weekends a year is plenty for me.

The AKC interviews you and also has requirements along the way that you’ve attended seminars, that you’ve visited with breeders, and that you’ve attended big dog shows. Specifically, they ask that you get to national specialties, which is when all the dogs are there, could be anywhere from 50 to 250 dogs, for some of these breeds. Also, the parent clubs, for example the American Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, also have a judge’s education function, where they help educate potential judges about the breed—maybe get some mentoring from people within the parent club, and also have some counsel from people who are involved with the breed and have been for a while.

The best dog show judges are a combination of engineers and artists. The engineers in them need to have all the parts in the right place and set at the right angles, and creating the dog that can do its job. The Standard really is kind of relating form to function. It describes the dog the way it should look to be able to best perform its function. So, if my Afghan Hounds are meant to be swift, running, hunting dogs, they’ve gotta have a body and legs that will do that. If they’re a sight hound, they have to be able to see, and be able to run down their prey and hold it for the hunter.

The Skye Terrier luxuriates in his splendid coat. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

So anyway, we’ve got the engineers. And then we’ve got the artists. The artists put it all together and get a pleasing picture of the dog—proper balance, proper breed type, the right parts that make it the breed that it is. The ears are a certain way, the eyes are a certain place, a certain shape. The muzzle is a certain length. And so, sometimes people can be a little more artist than engineer, sometimes they can be a little more engineer than artist. The best judges combine both of those things, which I think is necessary, really.

Going back to Afghan Hounds—we have variation in head types for example. Some of them, depending on your view, some of them you may think are more pleasing than others. And that’s important. If I’m concerned about heads, and how pretty they look, because it doesn’t always determine their functionality, then I’m going to like the head, and maybe I’ll give it a little more value in my judging. If I’m a movement judge, and I see a dog that’s a great mover, but maybe its head isn’t as pretty as the first dog I looked at, now I have to decide what’s more important to me—the head or the movement.

And that’s where, I think, the decisions start coming. We say we have dog judges who are movement judges, or “head hunters” as we call them, looking for the most beautiful head. And there are some breeds that, specifically are written in their Standard to say that this is a “head breed,” the head is the most important thing. And other Standards are written in a way that still leaves that to interpretation. But what happens in the dog show ring is, these judges don’t get to see the dog performing the job that it was bred to do, previously. Which is what the standard is theoretically written against. So as a judge, I have to be able to imagine this dog, that’s standing in front of me, performing the function that it was bred to do.

Excited or tired? Both? Either way, this French Bulldog is a cutie. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

What about judging against other breeds?

The judges are supposed to be judging each dog against its Standard. You’re not necessarily supposed to be judging this dog against this dog. But in the breed ring, you can’t help compare them a little bit to one another. When you get to the hound group, I’m comparing an Afghan Hound to a Dachshund. How am I to say this Dachshund is a better dog than this Afghan Hound? Well you’re not—you’re saying this Dachshund is a better Dachshund than this Afghan Hound is an Afghan Hound. Otherwise you’re comparing apples and oranges, because you have great variety in these groups. But everyone’s got their own little calculator going in their brain all the time, and they’re relating what they’re feeling with their hands and what they’re seeing in the ring, and looking at the dog, and seeing the picture with what goes on with the Standard.

A judge examines the dog while its handler stays vigilant. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

When they get to best in show—those are seven dogs who have all won their groups—if the judges have done their jobs, when they get into that final lineup, you’re probably gonna have seven pretty good dogs; they’re all good representatives of their breed. So now is when the other things enter into it like showmanship, and personality, and whatever you wanna call it—charisma, pizazz, something, owning the ground they stand over. Those things now come into play. The only challenge with that is, some dogs are supposed to be a little more reserved than others. Certain dogs, as we say in the business, are not gonna throw a stack on you in the ring that other dogs will. But there’s another saying—it’s a dog show, so you gotta show.

Is this all in people’s spare time?

The real heart and soul of our sport is the owner-handler, the people who come home from work on Friday night and pack the car and wash the dog and hit the road, and go to wherever the dog shows are on that Saturday or Sunday. Sometimes it’s a drive, and sometimes they might throw a dog in an airplane, and travel with them. Or sometimes it could be down the street. So, the activity is really designed around the owner-handler, and hopefully the family. And to take it a step further, we also use the term breeder-owner-handler, means the dog was born in their care, in their home. And we talk about that a lot too, because that’s a great part of the participation. You’re breeding dogs to create the next generation of healthy and happy dogs, hopefully a little bit better than the previous generation.

Say hello to the Dogue de Bordeaux. (Photo: Steve Donahue/See Spot Run Photos)

Are there any criticisms of dog shows that you think deserve some consideration?

No, I think when you think about dog shows, the real purpose has been through the years to identify superior breeding stock. Dog shows bring together people who care about their dogs, who care about their breed, and who want their breed to become healthier and happier to the point where they’re getting better at their function, whether they still get to do it formally or not anymore. And it also brings to the general public an educational aspect. It starts with finding the right dog to match your lifestyle and your family.

That’s the key thing about purebred dogs, and it’s not to advocate purebred dogs over non-purebred dogs, but the reality is that predictability is the key thing with purebred dogs, which is what we’re talking about with dog shows. I know that this dog is going to grow to be this big, and have this kind of hair, and this kind of personality. And if you have a mixed breed dog, you’re not always going to be able to know that. That helps, down the road, with dogs who grow up to be something you weren’t expecting—and those are dogs that often end up in shelters.

We always say, the real best in show will always be the dog sitting on the couch next to you.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook