What’s Going On With the Way Canadians Say ‘About’?

It’s not pronounced how you think it is.

Considering the geographical, cultural, and economic closeness of our two countries, it’s almost perverse that Americans take so much pride in their ignorance about all things Canada. Drake? Dan Aykroyd? The new hot prime minister? Is that it? But everyone knows what Canadians are supposed to sound like: they are a people who pronounce “about” as “aboot” and add “eh” to the ends of sentences

Unfortunately, that’s wrong. Like, linguistically incorrect. Canadians do not say “aboot.” What they do say is actually much weirder.

Canadian English, despite the gigantic size of the country, is nowhere near as diverse as American English; think of the vast differences between the accents of a Los Angeleno, a Bostonian, a Chicagoan, a Houstonian, and a New Yorker. In Canada, there are some weird pockets: Newfoundland and Labrador speak a sort of Irish-cockney-sounding dialect, and there are some unique characteristics in English-speaking Quebec. But otherwise, linguistically, the country is fairly consistent.

The Battery, part of the city of St John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. (Photo: Carolyn Parsons-Janes/shutterstock.com)

There are a few isolated quirks in Canadian English, like keeping the Britishism “zed” for the last letter of the alphabet, and keeping a hard “agh” sound where Americans would usually say “ah.” (In Canada, “pasta” rhymes with “Mt. Shasta”.) But aside from those quirks, there are two major defining trends in Canadian English: Canadian Raising and the Canadian Shift. The latter is known stateside as the California Shift, and it’s what makes Blink-182 singer Tom DeLonge sound so insane: a systematic migration of vowel sounds resulting in “kit” sounding like “ket,” “dress” sounding like “drass,” and “trap” sounding like “trop.” The SoCal accent, basically, is being replicated almost entirely in Canada.

But the Canadian Shift is minor compared to Canadian Raising, a phenomenon describing the altered sounds of two notable vowel sounds, that has much bigger consequences for the country’s identity, at least in the U.S. That’s where we get all that “aboot” stuff.

A postcard showing Broad Street in Victoria, BC. (Photo: Rob/Public Domain)

First catalogued in the 1940s and named by Jack Chambers in 1973, Canadian Raising is a shift found in Canada and in pockets of the northern United States (and, sort of, in Scotland) affecting two vowel sounds. The first is the sound in the word “write,” and the second is our old friend, “about.”

“Canadian Raising has to do with two diphthongs,” says Jennifer Dailey-O’Cain, a linguist at the University of Alberta who was raised in the U.S. but now sports a fully-functioning (but self-aware) Canadian accent. When we talk about accents in English, we’re almost exclusively talking about vowels; with the exception of dropping “r” sounds at the end of words, English dialects pretty much stick to the same consonant sounds. A “k” is a “k” is a “k,” you know? Not vowels. “These vowel sounds are very slippery and difficult to imitate,” says Taylor Roberts, a Canadian linguist who maintains a popular page on the topic of the Canadian dialect. “Consonants are easy, but vowels are tricky.”

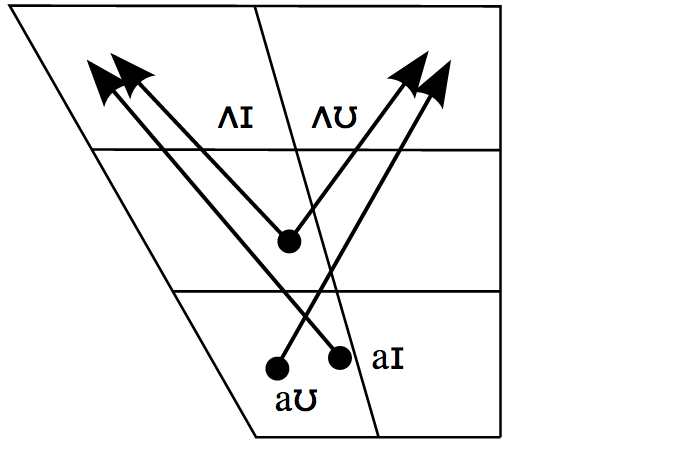

Different vowels are produced by moving the tongue in different parts of the mouth, tapping and curling and poking, while the lips create circles and ovals of varying sizes. Linguists have a map for this, a sort of ungainly parallelogram, but it also helps to just repeat the word to yourself and feel carefully for where your tongue goes. (I have heard Canadians say the word “about” more times in the past week than in the entire four years I lived in Canada.)

Toronto skyline. (Photo: Lissandra Melo/shutterstock.com)

This map features all of the basic vowels in English: “ah,” “ee,” “oh,” “ooh,” “eh,” that kind of thing. Those are called monophthongs. When you combine them you end up with a whole new palette of sounds known as diphthongs, sort of a compound vowel. The vowel in the word “bike” is one of these, made up of either monophthongs “ah” and “ee,” in the southern and western U.S., or “uh” and “ee,” in the Northeast, Midwest, and Canada. This latter is an example of Canadian Raising.

For the word “about,” we have a diphthong in the U.S., as well. That “ow” sound is made up of an “agh” sound moving to an “ooh” sound. That first sound, the “agh,” is an extremely low vowel on that chart.

Canadians also have a diphthong there, but a much weirder one than ours. Instead of starting with “agh,” they start with a vowel that’s mapped in a mid-range place, but one that is, bizarrely, not represented in American linguistics, period. This is an exclusively Canadian sound, one that the vast majority of Americans not only don’t use where Canadians use it, they don’t use it at all. It’s completely foreign.

Vowel chart of Canada Raising. (Photo: Peter238, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Canadian diphthong in “about” starts with something closer to “eh,” and migrates to a blank space on the American linguistic map somewhere between “uh,” “oh,” and “ooh.” That transition is actually easier on the mouth than the American version; our vowels go from low to high, and theirs from mid to high.

To say that Canadians are saying “aboot” is linguistically inaccurate; “ooh” is a monophthong and the proper Canadian dialect uses a diphthong. “A-boat” would actually be a bit closer, though of course it depends on how you pronounce the word “boat.” In most of the United States it can be all sorts of different diphthongs; in Philadelphia, it’s something like “eh-ooh,” though the most common pronunciation would be more like “oh-ooh.” In the Upper Midwest, though, it’s a monophthong, which is why it sounds so distinctive when someone from Fargo, North Dakota says “Fargo.” And in much of Canada, that tone is more similar to the Fargo accent than anything else. It might be close, but Canadians aren’t doing a monophthong in “about.” They’re not saying “a-boat.” They’re doing something that Americans simply can’t wrap their heads around.

“What’s going on is a compound of pronunciation and perception,” says Dailey-O’Cain. “The Canadians do pronounce it differently. Americans hear this and they know it’s different—they’re hearing a difference but they don’t know exactly what that difference is.” Americans do not have the Canadian diphthong present in the word “about,” which makes it hard to understand. We know that the Canadians are doing something weird, but in fact it’s so unlike our own dialect that we can’t even really figure out what’s weird about it.

Our best guess? Well, we can hear that the Canadians are raising that first vowel in the diphthong, even if we don’t know what “raising” means. But in a true American disdain for subtlety, we choose to interpret that as the most extreme possible raised vowel sound: “ooh.” It’s like a beach artist caricature that exaggerates a feature beyond realism and into cartoon-land: we hear a difference, and boost that difference to a height that isn’t actually correct anymore.

Prairies of Saskatchewan. (Photo: Martin Cathrae/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The big question is, well, why did this happen? What possible explanation can there be for the creation of this odd diphthong just north of the border?

Linguists do not generally attempt to answer questions of causality. “Why? I can’t answer that,” said Dailey-O’Cain when I asked. “You can look at ongoing changes sometimes if you have the right kind of data but it’s very, very hard.” But there are theories. One particularly fascinating explanation has to do with what’s called the Great Vowel Shift. If you’ve ever wondered why English is such a legendarily horrible language to learn, a lot of the problems can be traced back to the Great Vowel Shift.

The only other Canadian export to America besides “aboot” and Drake seems to be poutine. (Photo: Quinn Dombrowski, CC BY-SA 2.0)

There is no firm date on the beginning and end of the Great Vowel Shift, but at most, we can say it happened between the 1100s and the 1700s, with probably the most important and biggest changes happening in the 1400s and 1500s. This coincides with the shift from Middle English to Modern English, and also with the standardization of spelling. The shift itself? Every single “long vowel”—”ey,” “ee,” “aye,” “oh,” “ooh”—changed. (Nobody knows why. Linguistics is turtles all the way down.)

Before the Great Vowel Shift, “bite” was pronounced more like “beet.” “Meat” was more like “mate.” Everything just kind of slipped one notch over. This happened in stages; that first word, “bite,” started out as “beet,” then became “bait,” then “beyt,” then “bite.” You can hear a nice spoken-aloud rundown of those here.

If you’re wondering what the difference between “bait” and “beyt” is, well, there you have one possible origin of Canadian Raising. “Beyt,” one of the later but not the final stage of the Great Vowel Shift, is extremely similar to the Canadian Raised sound spoken today. There is a theory—not necessarily accepted by all—that Canadian Raised vowels are actually a preserved remnant of the Great Vowel Shift, an in-between vowel sound that was somehow stuck in amber in the Great White North.

Maybe a certain population of Englishmen from that particular time period, around 1600, landed in Canada and due to its isolation failed to observe the further changes happening in England. Maybe.

But I like this explanation. Canadians aren’t weird; they’re respecting the past. One very specific past, that everyone else skipped on by. It’s an awfully nice-sounding diphthong.

Correction: This article originally misspelled Dan Aykroyd’s surname. The article has also been updated since it was first published to expand on the role that monophthongs vs. diphthongs play in the Canadian pronunciation of the word “boat.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook