Why is This Space-Age Car Slamming into a Wall of Flaming TVs?

How a photographer landed an iconic shot of the 1975 performance piece “Media Burn.”

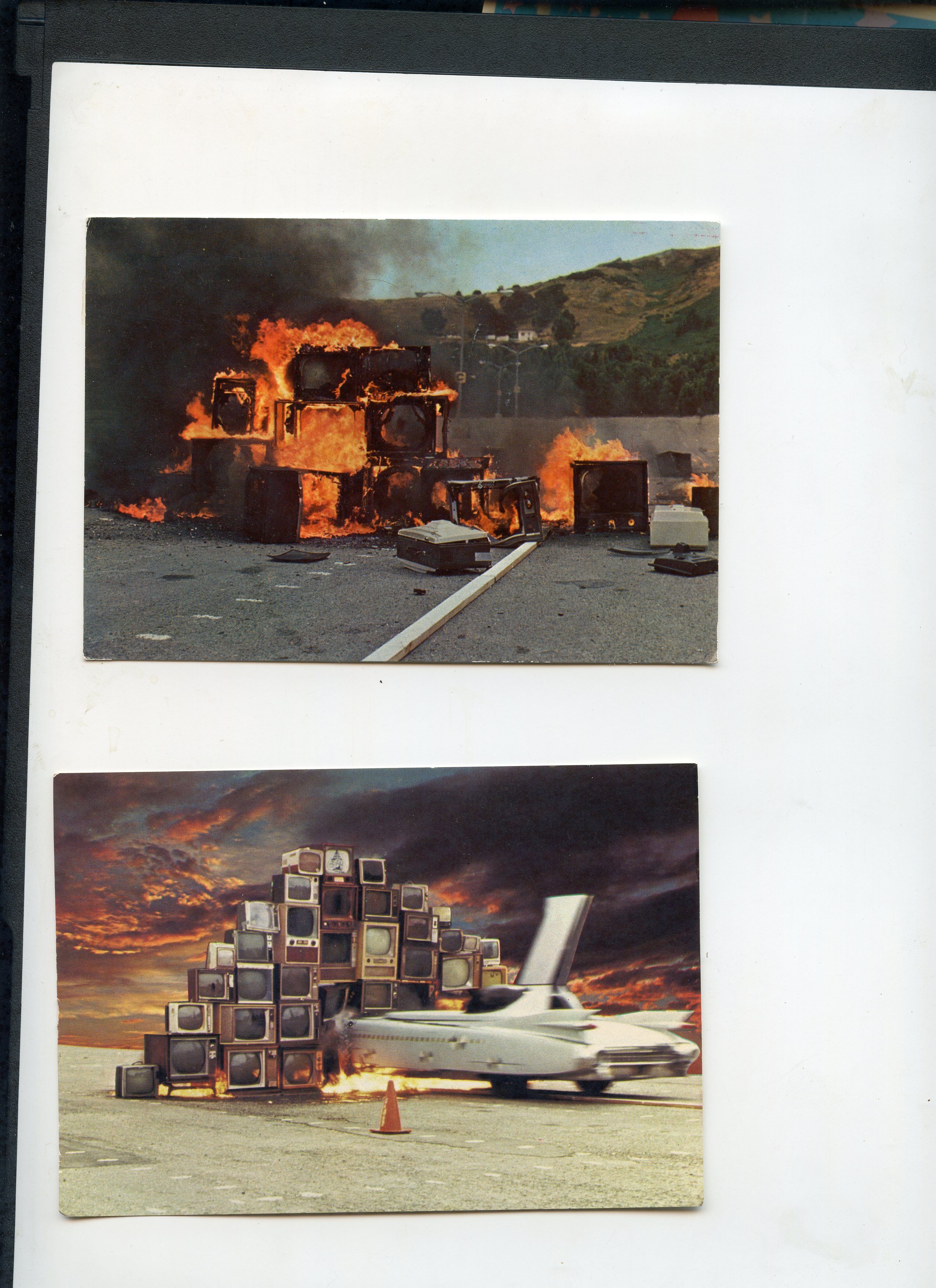

On a bright, clear Fourth of July in 1975, a crowd of onlookers and reporters assembled in the vast parking lot of the Cow Palace, a convention center just outside San Francisco. They had been summoned by a curious press release that read in part: “On July 4, 1975 members of Ant Farm will drive a Phantom Dream Car thru a wall of burning television sets in an event called MEDIA BURN.”

The irreverent Ant Farm art collective had been putting on performances and making attention-grabbing installations since the late 1960s. By 1975 they had already made one of their most iconic pieces, Cadillac Ranch, a sculpture in Amarillo, Texas that consisted of ten Cadillacs sunk nose-first into the earth. (The cars are still standing today, in a cow pasture near interstate 40, and have accumulated a skin of vibrant graffiti.) The group were frequent media critics, and for their latest stunt they would use the media to assist them in the critique.

John Turner, one of the invitees, had just started working for the media in 1975. He was working as a part-time editor for a few news stations in San Francisco; later that year he would become an arts reporter and producer at a local channel. He had also mingled with Ant Farm socially, hanging out at the group’s San Francisco studio. He had some idea of what the collective was planning and knew it would be worth documenting, so he attended with a Pentax camera in hand.

The scene was odd and also festive. Women in hotpants hawked souvenir t-shirts, programs, and posters. Camera crews amassed behind yellow barriers. A Basset hound in a cape wandered around. As promised, a pyramid of old-fashioned television sets was assembled on the concrete, with the largest on the bottom. The group had also set up a grandstand decorated with patriotic regalia.

Turner already had an idea of how things would go down, so he arrived ready to get his shot.

“I scoped it out, and I thought, ‘Well, for me, the best vantage point is probably about twenty five to thirty feet away from the sets,” he told me in an interview. So he claimed a spot, placed the camera on a fast shutter speed, framed his shot, and waited.

Things happened quickly. A car arrived bearing “John F. Kennedy” (artist Doug Hall) and a bevy of faux Secret Service agents. Kennedy/Hall mounted the star-spangled stage and delivered a speech praising the “pioneers” who would pilot the Phantom Dream Car. He asked the audience: “Who can deny that we are a nation addicted to television and the constant flow of media?”

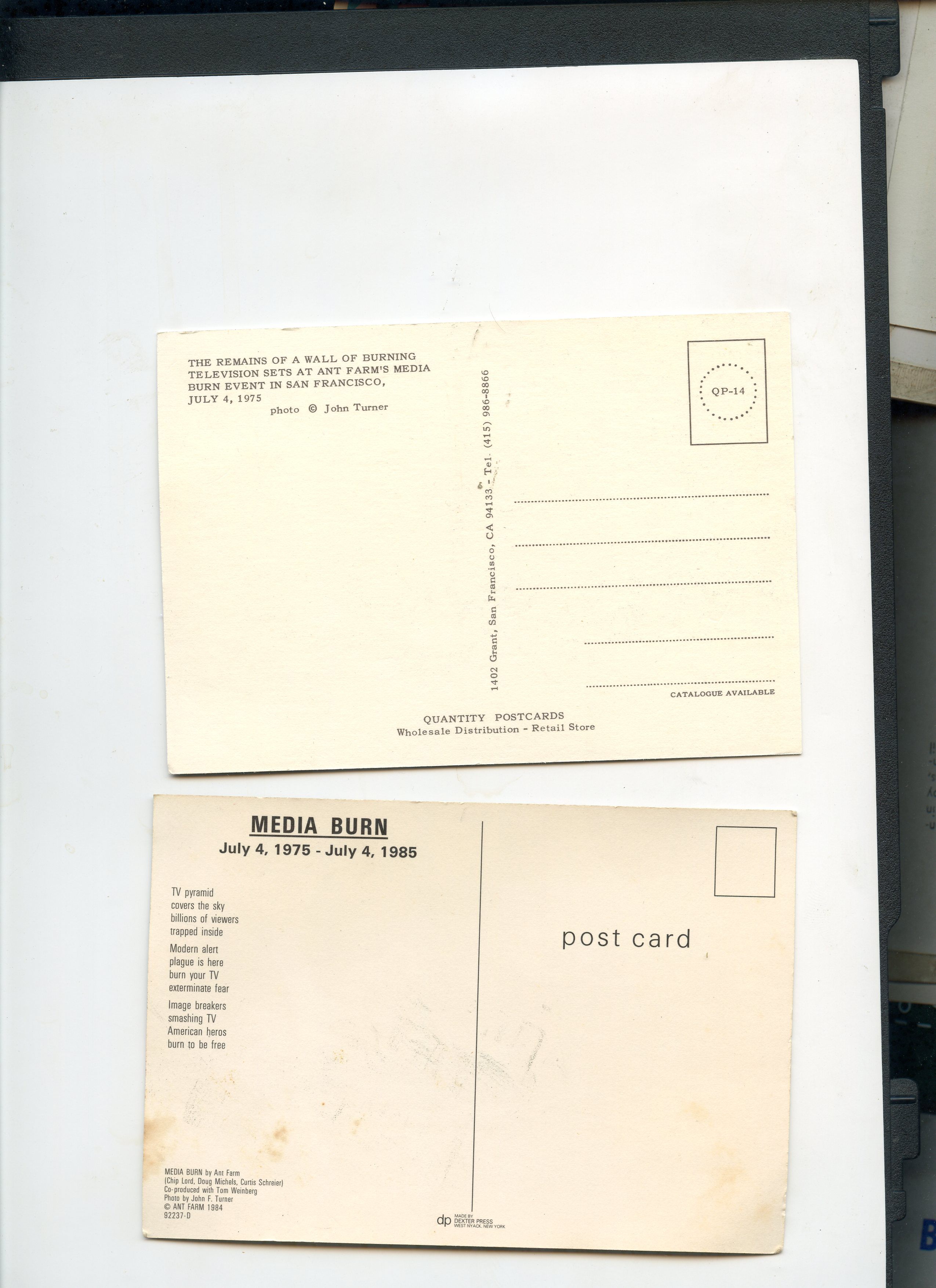

Once the speech had ended and the fake president was spirited away, the Phantom Dream Car was unveiled. A spacey marvel, the modified Cadillac convertible looked like it had arrived from the set of a science fiction film. Where a front windshield would normally be were two clear domes; jutting from the top of the car was a massive fin containing a camera. Once the drivers were in the car, the clear plastic domes would be shrouded in protective black fiberglass. The drivers would pilot their vehicle via the closed-circuit camera, which sent a live feed to a monitor mounted in their dashboard. The pyramid of televisions would then be doused in gasoline and set on fire, and the Phantom Dream Car would plow through them at about 55 miles per hour.

Turner knew that his success depended on a matter of seconds.

“If I was watching the car coming from behind me, I would have definitely missed the shot or the focus would have been jarred,” said Turner. “So I thought, ‘The easiest way to do this is to just do it by audio.’ So what I did is, when I heard them start the car, I took a look back, and then I turned my head and as I heard the sound getting closer to me, I gauged where the car was and I decided to take the photograph as I saw maybe a fraction of the front of the car enter my camera frame.”

The car slammed into the pyramid of televisions with what Turner described as a “thump,” but he couldn’t tell you what it actually looked like. He was listening so hard trying to get the shot, he said, that he didn’t see the action.

“From the time that the thing was lit to the cars actually hitting the center target or wherever they were aiming for, it was probably under ten seconds,” Turner told me. “So there really wasn’t time for me to get a good waft of the smoke or even see the fire. The part of my brain that was paying attention to audio was on adrenaline.”

Once the smoke and the crowds cleared, Turner sent his Kodak film off to be developed. “It happened so slam-bang I had no idea if I had gotten a useable image,” he said.

In fact, he would find, his audio trick had worked; he managed to capture the Phantom Dream Car at the moment it explosively collided with the television pyramid. The otherworldly vehicle’s nose is submerged in the sets, their neat pyramid only just beginning to cave as vibrant yellow and orange flames spread beneath and above. Behind is the incongruous scenery of rolling hills and green trees. It’s a wonderfully confounding image.

Turner is sanguine about his success; he called it a “lucky shot”, if luck is “skill and opportunity meeting at the same time.” He compared it to a scientific image that captures a specific and fleeting moment, like a bullet shattering on impact.

“There were other people there taking the same photograph and mine just happened to be, through this moment of luck, an interesting view,” said Turner. “Because it gave a sense of location and noise and fire and danger and all these things.”

Turner knew he had a good shot, and he showed it to Chip Lord, one of the founders of Ant Farm. Lord liked it, too, and asked if he could turn it into a postcard. Turner agreed. Suddenly the image had a life of its own.

The postcards were a runaway success; mail art was wildly popular in the 1970s and the bizarre image of a futuristic car ploughing through television sets captivated people who sent them all over the world. Copies are still circulated on eBay, where collectors snap them up.It was a document of an audacious art piece, a visual thumbing of the nose to powers-that-be, and an anarchic celebration of destruction.

“The event was only attended by maybe 300 people, including news media and friends of the artists,” says Turner. “But this postcard had a kind of life, an afterlife, and an after-afterlife, and then it just became like pop culture photography.”

The image proliferated. In addition to the postcards, it appeared in art books around the world, in a pamphlet for an early MTV awards show, on the cover of a German pop album, and in museums. Turner got used to seeing his photo in unlikely places. And in spreading the image of Media Burn far and wide, he also became, in a way, part of the act.

“Though this high-octane performance would appear to be Media Burn, it was, in actuality, not,” writes Constance Lewallen in Ant Farm 1968-1978, a catalog produced for the first major Ant Farm retrospective in 2004. “The performance attained its raison d’etre not in the fiery collision, but in its transformation to an image: it was in that singular moment when the Vidicon tubes blinked that Media Burn occurred—or, perhaps more correctly, when “Media Burn” arrived at Media Burn.”

In other words, the video produced by Ant Farm, the hundreds of photos taken by spectators, and the news reports that were issued afterward became the core of the art project, not the ephemeral stunt itself. And Turner just happened to snap an iconic image of an image-fueled experiment.

In the ensuing years, Turner—who still lives in the Bay Area and still receives requests to use his Media Burn photo—has had a long career in television, written books on seminal folk artists, and made a movie about mysterious musician Korla Pandit. He has also watched the nature of photography shift radically from waiting for Kodak to send images back from the lab, to children snapping hundreds of digital images daily. In his estimation, he told me, this change has been an improvement.

“In today’s day and age of the camera phone, there are so many lucky shots taken every day throughout the world, that capture moments of impact or moments of high emotion,” says Turner. “Just because somebody holds up an instrument and decides to press a button, they get these amazing images and I’m constantly surprised and impressed.”

But even though digital wizardry has ushered in a new era of lucky shots, Turner says he never again got a shot quite so lucky as the one he captured with nothing more than a handheld Pentax, instinct, and the sound of a roaring Phantom Dream Car just outside the frame.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook