Why It Was Faster To Build Subways in 1900

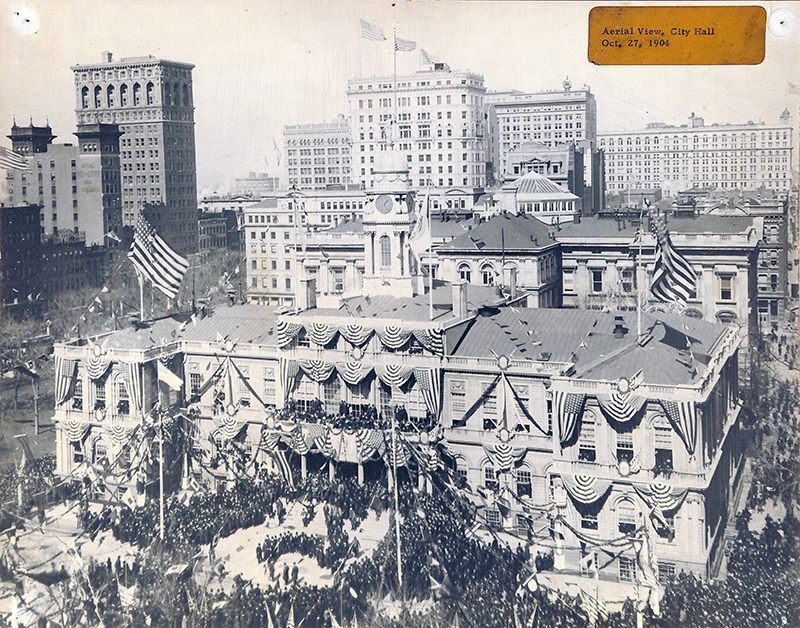

Opening day ceremony for the first subway line at City Hall, October 27, 1904. (Photo: Courtesy of the New York Transit Museum)

When New York City Mayor Robert Anderson Van Wyck lifted the first shovel of dirt from the ground outside City Hall on March 24, 1900, the city celebrated the beginning of its first subway tunnel. It was heralded as “one of the most important events in the history of the city,” according to a story that appeared in the New York Times the next day, which described the crowd as immense, unruly, and “eager for souvenirs.”

But the thousands of onlookers who gathered in excitement hadn’t seen the start of the subway’s construction at all. What they saw was a symbolic photo op.

The system’s groundbreaking actually happened two days later and over a mile away on Bleecker Street, when chief engineer William Barclay Parsons drove a pickaxe into the ground.

The image of a single engineer wielding a piece of technology no more sophisticated than a hammer isn’t what most people have in mind when they think of modern infrastructure projects. But it may be the fastest technology available to New Yorkers, even now—especially now, as the Second Avenue subway, a project that began planning in the 1910s, has been under construction since 2007, is not yet open. By contrast, workers laid over 9 miles of track across Manhattan in only four years after initial groundbreaking. “The fact that we still don’t have a subway under Second Avenue is kind of amazing,” says Polly Desjarlais, a senior educator at the New York Transit Museum.

So if we could build a new subway line in four years back in the early 1900s, why is the Second Avenue line taking so long? Why are we still using so much infrastructure that’s more than 100 years old? What has changed in the last hundred or so years for the subway?

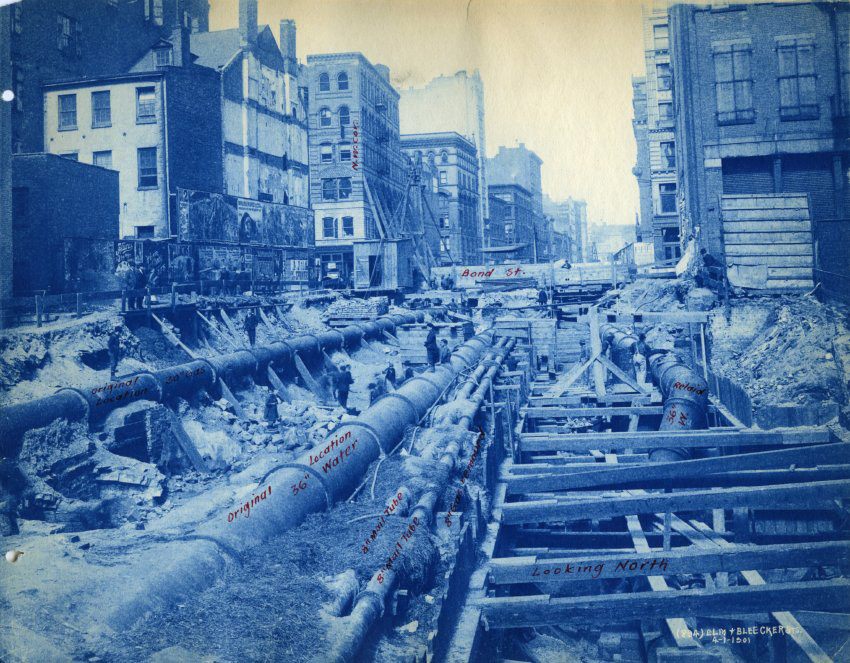

Groundbreaking at Bleecker and Green Streets, March 1900. (Photo: Courtesy of the New York Transit Museum)

Labor conditions, for one. For better and for worse, it was easier to launch a major construction project before there were labor and safety regulations in place. While newer tunnels may not seem dramatically different from their predecessors, the built environment and social conditions that make them possible have dramatically shifted.

Much of the city’s first subway line was built using a method called “cut and cover,” for instance, which essentially involved digging giant trenches through existing streets, laying tracks and covering them back up. “They were digging the hole basically from the ground,” says Elyse Newman, the transit museum’s education manager. “All traffic on Broadway had to stop at certain times over the course of this construction, which is crazy because it was really disruptive to the city.”

Cut and cover hasn’t been abandoned—it was used for part of the new Fulton Center—but “you could never, ever do anything like this now” on the same scale, says Desjarlais. In the early years of construction, engineers simply didn’t have to relocate huge numbers of people or dig deep, expensive tunnels into the earth if they wanted to build a subway. Instead, planners could just put a giant hole in the street. “They didn’t have to deal with property rights,” Desjarlais adds. “You have 9 million people that you have to get around today.”

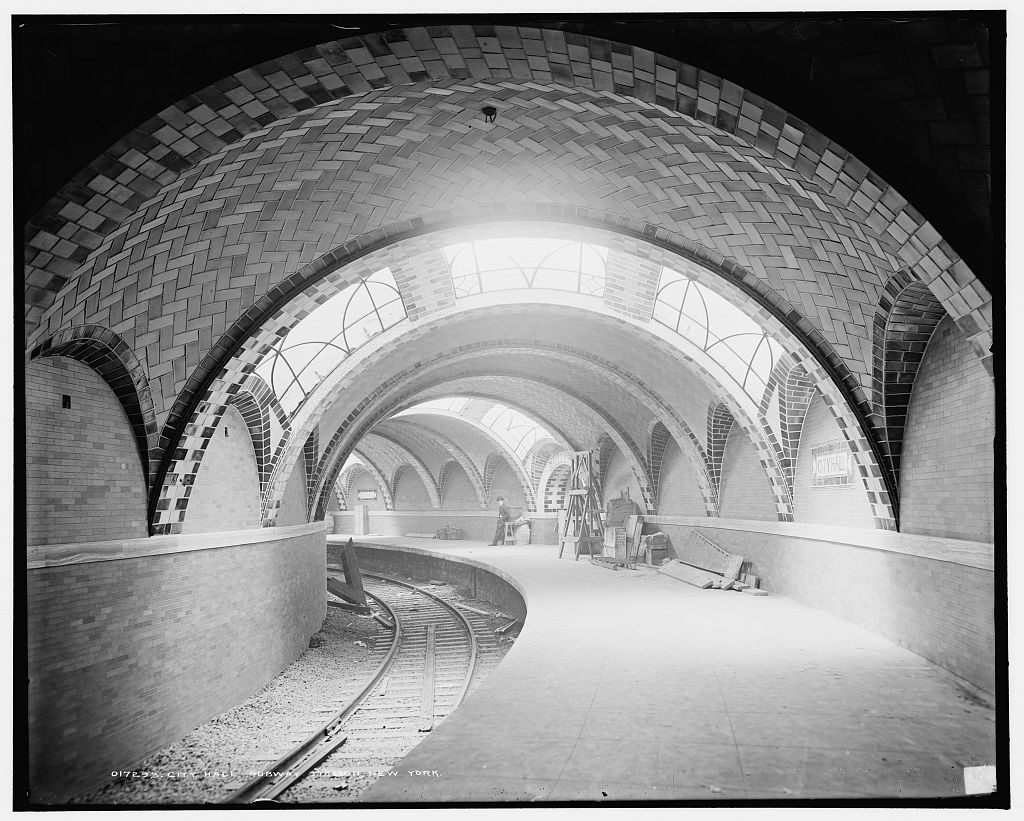

The City Hall station of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line opened on October 27, 1904. (Photo: Public Domain/Library of Congress)

Also crucial to the original tunnel’s speedy construction was the sheer number of workers deployed and the conditions they were expected to endure. Somewhere between 7,700 and 12,000 people were involved in building the first line, according to Desjarlais, and most of the workers wielding pickaxes were only bringing home around $1.50 per day.

“You have these guys down there who are literally banging at the rock with shovels,” says Newman. And it’s not like there were generous benefits or protections. “I think they were just working insanely. There were many fewer regulations in terms of public safety [and] public health.”

Workers completed tunneling for the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway in 2011. (Photo: MTA/flickr)

But even though there aren’t massive numbers of workers streaming into modern subway construction with pickaxes, haven’t technological advances made the whole process more efficient and cost-effective, thereby making additions to the subway even easier? It’s a question Desjarlaissays she gets all the time. The answer is that 115 years of advancement doesn’t necessarily balance out the ways in which the city’s infrastructure is more complicated to disrupt than it was in 1900, or the political challenges in securing long-term funding.

Elm (Lafayette) Street and Bleecker Street, NY, April 1, 1901. (Photo: Courtesy of the New York Transit Museum)

And while projects like the Second Avenue subway are being built partly by enormous boring machines that would have been unfathomable a century ago, the original tunnel on Bleecker street may never look like an artifact. The trains are still running in tunnels that are fundamentally the same, powered by the same third-rail electrification scheme that was in place when the subway opened. Even the original stations were peppered with ads.

“The bones of the system are exactly the same,” says Newman. “The engineering and the concept was so successful that here we are and it works relatively—relatively well.”

Still, that’s probably not much consolation to anyone who has ever been jammed into into the city’s overcrowded east side subways. But to those complaints, the original engineer Parsons might have said: it’s never too late to grab a pickaxe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook