Why It’s Still a Struggle to Put Women in Space in 2016

The German search for its first female astronaut is only latest in long string of fits and starts.

Jerrie Cobb, in the Altitude Wind Tunnel in April 1960. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Claudia Kessler is currently sifting through applications for Germany’s first female astronaut. That’s right—first. In 2016, all 11 of Kessler’s compatriots who have been to space so far have been men.

Kessler is CEO of the aerospace recruiting company HE Space. (That unfortunate name was based on a founder’s name, not the male pronoun, but she joked that she’s wanted to change it to SHE Space.) As the European Space Agency isn’t likely hiring new astronauts any time soon, Kessler has taken the matter into her own hands. She launched her private initiative called Die Astronautin in March. Her plan is to eventually train two finalists and pick one for a weeklong journey to the International Space Station. The mission would take place in 2020, at the earliest, and it would be funded through a mix of sponsors and crowdsourcing.

If Kessler succeeds, she would only slightly shift the overall gender imbalance in spaceflight. To date, more than 540 people have been to space . Just 59 of those astronauts have been women.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that spaceflight—like many science and tech fields—has traditionally been dominated by men. What may be surprising is that some women (and men) were pushing for gender diversity in space before any human had even left the planet. A look at an early chapter in the history of spaceflight might explain why progress for female astronauts has come in fits and starts.

Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman to go into space, in 1963. (Photo: ESA)

In the 1950s, American aerospace researcher Randy Lovelace developed a rigorous medical test to qualify NASA’s first astronauts for space travel, the Mercury 7, who included Alan Shepherd and John Glenn. Lovelace was basically a weeklong physical that used the most intense tests available to uncover health defects that could possibly compromise an astronaut exposed to the rigors of spaceflight. The candidates were subjected to a litany of X-ray scans, heart checkups and circulation tests. They also floated in dark isolation tanks for hours, and they were put into a coffin-sized radioactivity counter that doubled as a claustrophobia test.

Outside of NASA’s official astronaut training program, Lovelace was curious about how women would fare in his exam.

At the time, there was a lot of public discussion around the prospect of female space travelers, says Margaret Weitekamp, a historian and curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The Man and the Challenge, a fictional TV show about an aerospace medical researcher, included a plot in 1960 about how women would do in space simulations. The real-life scientific community had good reason to think that women might be better suited physically for flying in a small spacecraft, where every pound takes up precious (and expensive) real estate. On average, women are lighter and smaller than men, and they require less food, less water and less oxygen. Women also tend to have better cardiopulmonary health, and in the 1950s they were outperforming men in isolation tests, Weitekamp said.

Seven of the original “Mercury 13” at Kennedy Space Center in 1995. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Survival inside cramped space capsules wasn’t the only concern. The public and scientists alike were envisioning a future where space stations would orbit Earth, housing astronauts for years at a time. So naturally, the question of sex came up. And the discussion wasn’t always decorous. In 1962, the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun commented on the possibility of female astronauts by repeating a joke that NASA was “reserving 110 pounds of payload for recreational equipment.”

Author Martin Caidin had taken the issue a little more seriously in his 1958 cover story on space travel in the men’s magazine Real. Caidin was concerned about “the enormous sexual problems” that would arise if astronauts were sent into space with an all-male crew at the peak of their sexual prime. He said castration, homosexuality and celibacy were unacceptable options. On these terms, he generously offered that “there’s no reason in the world why a woman wouldn’t do as well as a space ship crew member as a man.”

Astronaut Mae Jemison on the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 1992. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Lovelace had a less offensive, though still gendered, role for women in mind. He couldn’t foresee how advances in computers and digital cameras would take some burdens off humans in space exploration. He imagined astronauts of the future would live inside sprawling space labs where they’d conduct experiments and complete reconnaissance missions with telescopes and binoculars—with the help of a female support staff.

“Lovelace was thinking that if you’re going to have such a large installation in space, you’re going to need secretaries, you’re going to need lab assistants, you’re going to need telephone operators, you’re going to need nurses, and that means we need to know whether women can survive being in space physically,” Weitekamp said. “On one hand, he’s very much a visionary in terms of space exploration, and on the other hand, he’s very much a product of his time.”

Lovelace launched a privately funded Women in Space Program. He invited a top young pilot named Jerrie Cobb to be the first woman to undergo his exams, and in 1960, she passed. In 1961, Lovelace sent letters to another 25 talented female pilots asking them to undergo his test at his clinic in Albuquerque. The exams were enthusiastically covered in the media with articles in magazines like McCall’s and Parade. Including Cobb, 13 women in total passed the test. They’ve sometimes been called the “Mercury 13.” But these women were never together as a group in the 1960s. And Weitekamp thinks the nickname probably perpetuates the misconception that this program was ever officially sanctioned by NASA—which it wasn’t.

Astronauts (L-R) Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger, Naoko Yamazaki, Stephanie Wilson and Tracy Caldwell Dyson, in 2010, marking the first time four women were in space at the same time. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

The Lovelace women were supposed go undergo further aeromedical tests during jet flights at a military base in Pensacola, Florida. In her book Right Stuff, Wrong Sex, Weitekamp describes how Lovelace asked the Pensacola base to wire the Pentagon to find out if they could use military equipment to determine difference between male and female astronauts. They received a joke in reply: “If you don’t know the difference already, we refuse to put money into the project.” Cobb eventually was able to undergo—and pass—the simulation testing in Pensacola, but the program was canceled before the other women could participate. Weitekamp said the Pentagon didn’t want to seem like they endorsed any qualifying tests for female astronauts.

In 1962, some of the Lovelace women testified during a congressional hearing about whether NASA was discriminating on the basis of sex. (This was before sex discrimination was even made illegal by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.) The complaints were ultimately dismissed. NASA reasoned that its astronaut candidates had to be jet test pilots, and women were explicitly excluded from becoming jet test pilots at that time because it was deemed too dangerous.

Weitekamp thinks NASA ultimately didn’t pursue a testing and training program for female astronaut candidates because such a move would have been considered some kind of “social experimentation.”

Expedition 16 commander Peggy Whitson, the first female commander of the International Space Station, pictured in 2008. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Political considerations became paramount. “I don’t know that people always remember that when John Kennedy gets up before a joint session of Congress on May 26, 1961, and sets the goal that we’re going to go to the moon by the end of the decade, the U.S. had only 15 minutes of human spaceflight at that point, and only suborbital,” Weitekamp said. “They end up on a track toward this lunar goal. NASA somewhat streamlines this program toward this goal and is really not interested in what it would have seen as social experimentation.”

It was up to the Soviet Union, the only other major space player at the time, to shatter the cosmic ceiling. When cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in June 1963, NASA largely dismissed her feat as a stunt. And though Tereshkova was chosen from a pool of several trained female cosmonauts, the Soviets didn’t send another woman to space until Svetlana Savitskaya’s flight in 1982. Tereshkova recently told BBC News that the space program authorities deemed it “too dangerous” to send another woman to space after her milestone mission.

NASA’s first six female astronaut candidates, pictured in 1979 (L-R): Shannon W. Lucid, Margaret Rhea Seddon, Kathryn D. Sullivan, Judith A. Resnik, Anna L. Fisher, and Sally K. Ride. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Tereshkova’s flight reopened the wound for those who had hoped Lovelace’s Women in Space Program would be taken seriously. In July 1963, Life magazine printed pictures and short bios of the 13 Lovelace woman with a withering article under the headline “The U.S. Team Is Still Warming up the Bench.” The author, Clare Boothe Luce (who was a playwright, congresswoman, ambassador and fascinating figure in her own right), wrote, “The U.S. could have been first to put a woman up in space merely by deciding to do so.”

“The Lovelace women were ahead of their time,” Weitekamp said, noting that there was a distinct lack of organized feminist groups to advocate for them. “The idea of sex discrimination wasn’t enshrined in law in any way that would help them. I think that when you look at these histories, it’s not the slow steady progress that one might sometimes hope for.”

Jerrie Cobb next to a Mercury spaceship capsule. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

In 1978, NASA finally chose its first female astronauts, six mission specialists in a class of 35. By then, civil rights activists and second-wave feminists had raised the national consciousness about equality. And the leaders of space agency realized their Astronaut Corps needed to better reflect the face of country—in other words, it couldn’t be made up of just white men. NASA even brought in Star Trek actress Nichelle Nichols to help recruit women and minorities. The design of the Space Shuttle also allowed for a greater diversity of astronauts; the program was newly open to scientists and doctors outside the more homogenous pool of candidates that came from military flying programs. Still, the women of the 1978 class had to navigate an organization that wasn’t always used to having women in the room. Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, was asked if 100 tampons would be enough for her 7-day mission.

The future is a little brighter for gender equality in space. NASA’s most recent class of astronauts, announced in 2013, is 50 percent female. They’re the first group of space flyers who could be selected to go on a mission to the Red Planet. That means we might have a shot of getting the gender balance right when we become an interplanetary species. “If we go to Mars, we’ll be representing our entire species in a place we’ve never been before,” one of those new astronaut candidates, Anne McClain, told Glamour magazine earlier this year.

In the private industry, some women have risen to high-power roles, like Gwynne Shotwell, who is president and COO of Elon Musk’s company SpaceX. Russian space officials, too, have stepped up their game. Last year six women successfully completed an 8-day mock lunar mission, ahead of a future Russian moon mission planned for 2029. “There’s never been an all-female crew on the ISS,” experiment supervisor Sergei Ponomaryov reportedly said. “We consider the future of space belongs equally to men and women and unfortunately we need to catch up a bit after a period when unfortunately there haven’t been too many women in space.”

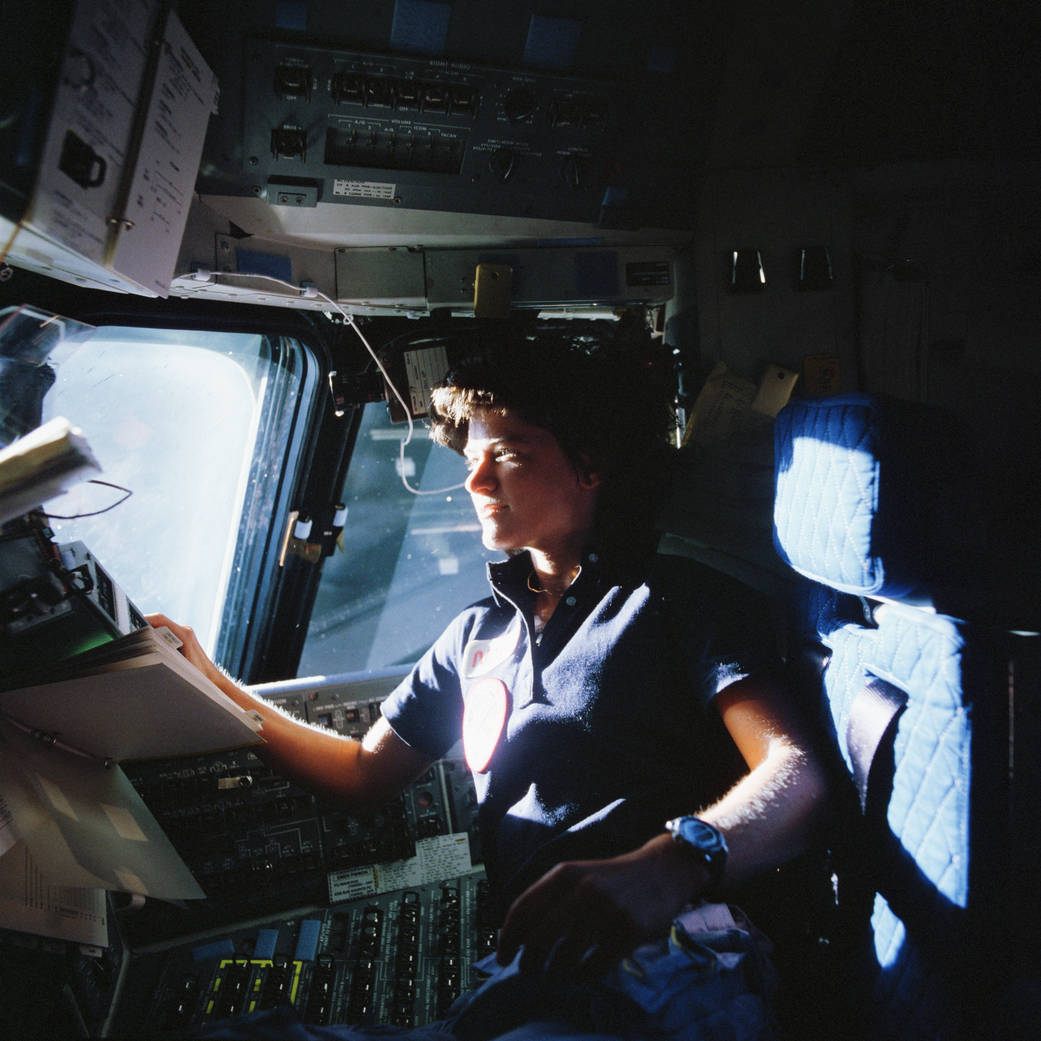

Sally K. Ride, the first American woman in space, shown here on board the Challenger in 1983. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Despite better representation, women in the industry still have to deal with sexism. Those women who took part in the mock moon mission were asked how they would live without men or makeup for a week. Before her flight in 2014, Russian cosmonaut Yelena Serova was asked during a press conference how she would bond with her daughter and take care of her hair during her stay aboard the International Space Station. Gesturing to her fellow male cosmonauts, Serova shot back: “Can I ask a question, too? Aren’t you interested in the hair styles of my colleagues?” Female NASA astronauts who have kids are inevitably asked about being away from their families for long stretches of time. It’s hard to imagine the same being asked of their male counterparts or splashy headlines about an “Astronaut Dad.”

“There is a lot of attention paid to the first women to do something,” Weitekamp said. “Equal credit needs to be given to the women who follow in their wake who don’t have to deal with as much public scrutiny, but who are nonetheless held to a very high standard.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook