About

Modern-day Berlin abounds with traces of the violence from 1945 when the Red Army ground its way through the city and the Nazi government made its last stand in the underground Fuherbunker. Public buildings from the era like the Pergamon Museum have facades that are still pockmarked by machine gun bullets and artillery shrapnel.

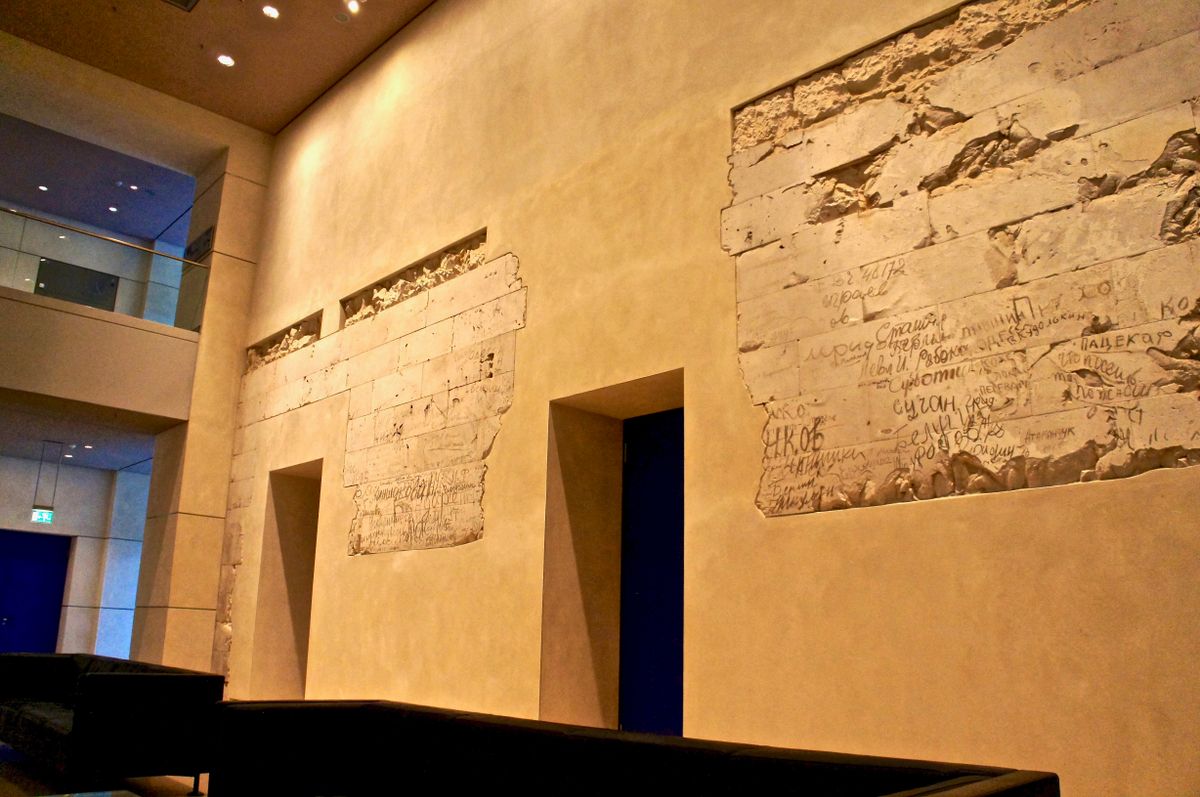

One of the most evocative—and controversial—bits of scar tissue from World War II is found in the Bundestag itself, the home of Germany's parliament, where some of the walls are still covered with graffiti left over from the Soviet takeover.

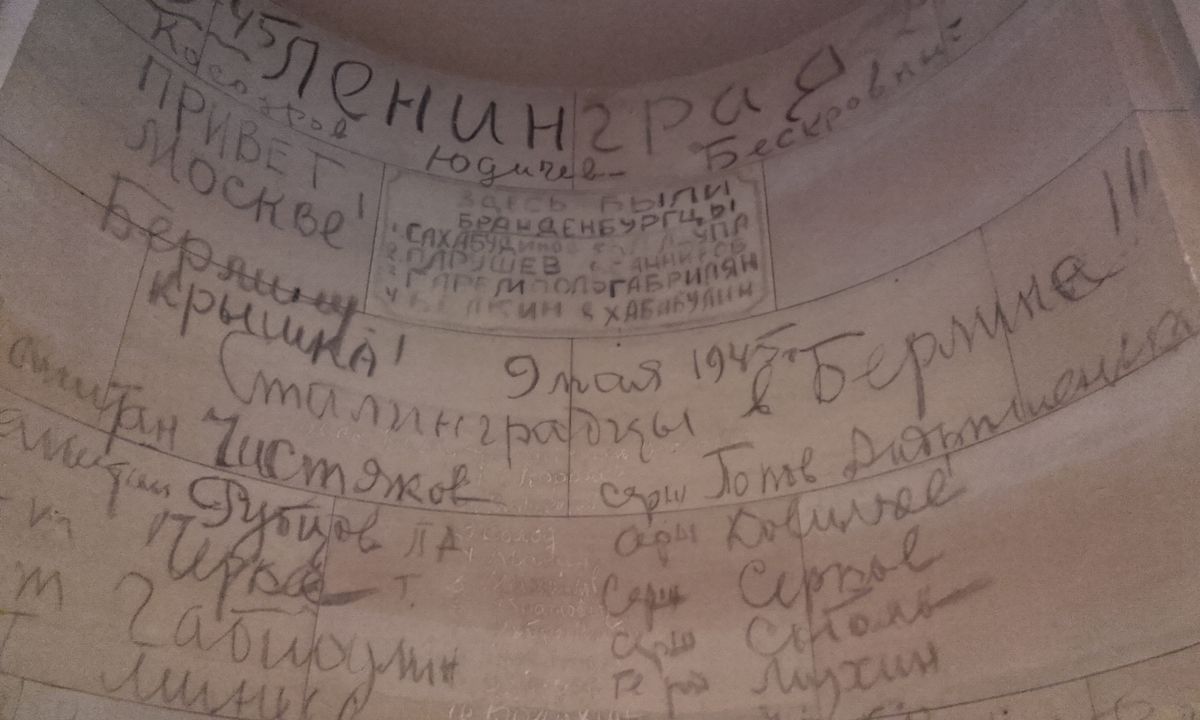

The Reichstag (as the parliamentary building was then known) was a highly prized target by Joseph Stalin for its symbolic importance. Interestingly, while the Soviets thought of the Reichstag as “Hitler’s Lair” it was actually anything but—the German dictator loathed the Parliament and had never given a single speech there. Regardless, when the Soviets finally gained control of the building on May 2, 1945 the first thing they did was stage a photo op as a triumphant Hammer & Sickle flag was planted on the roof.

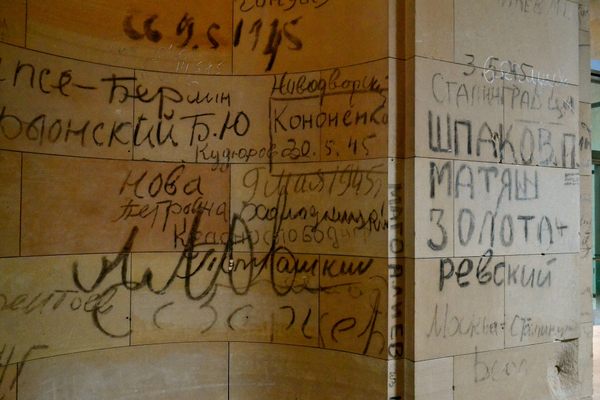

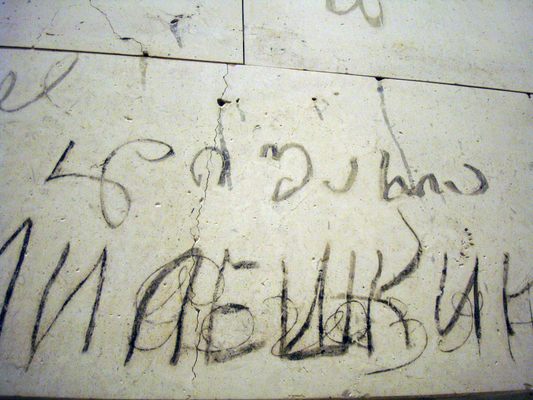

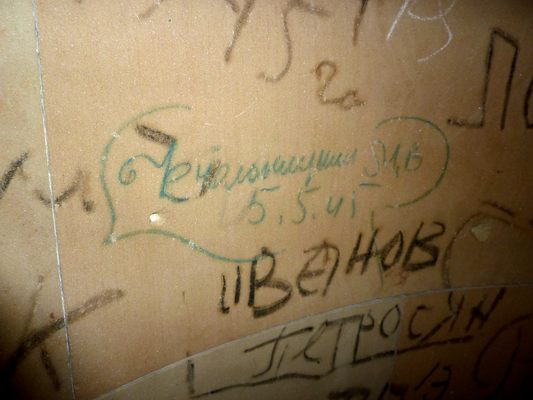

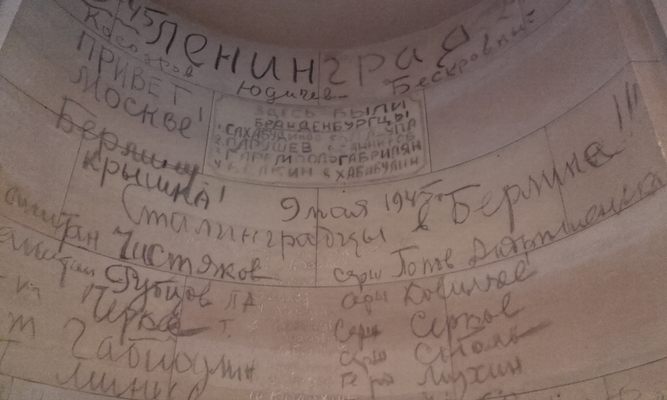

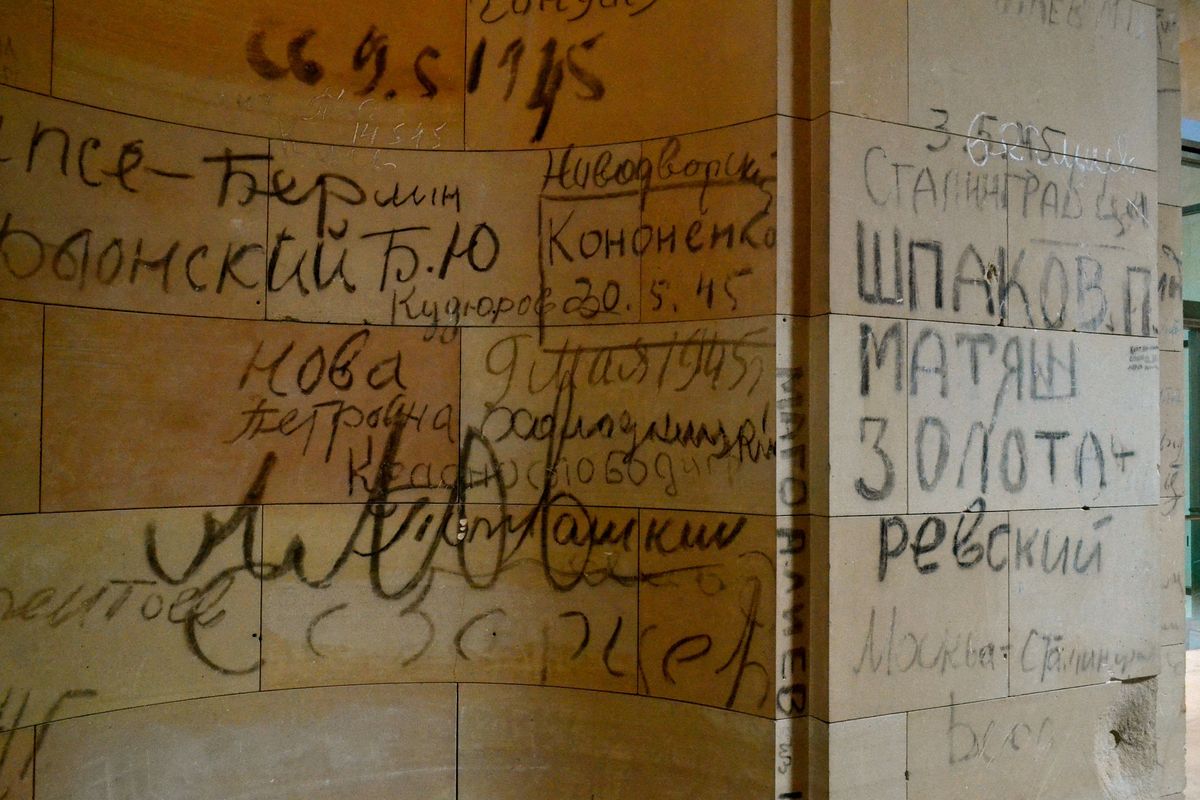

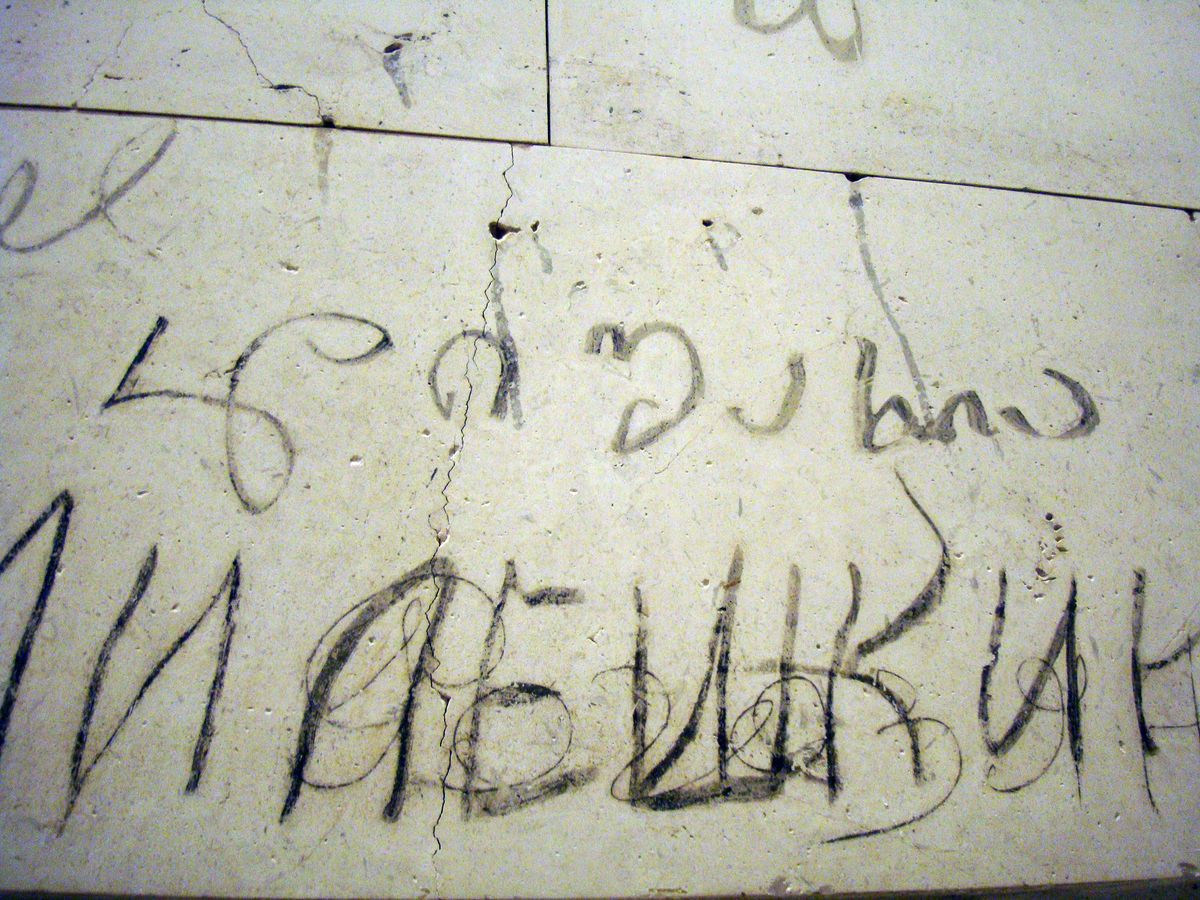

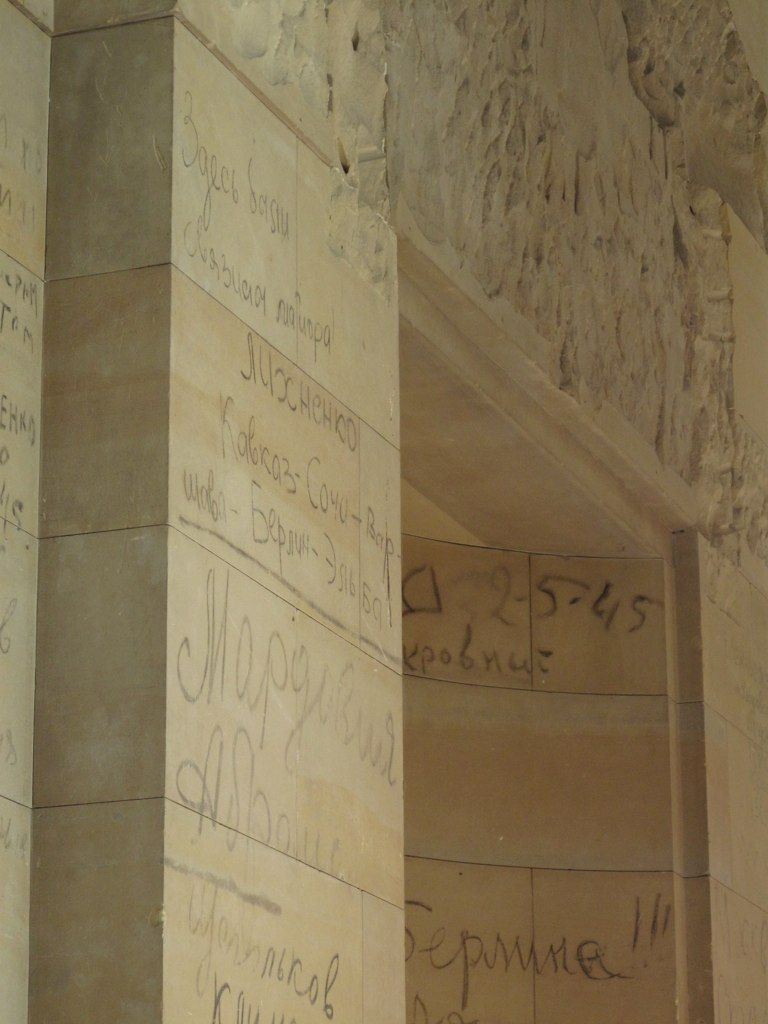

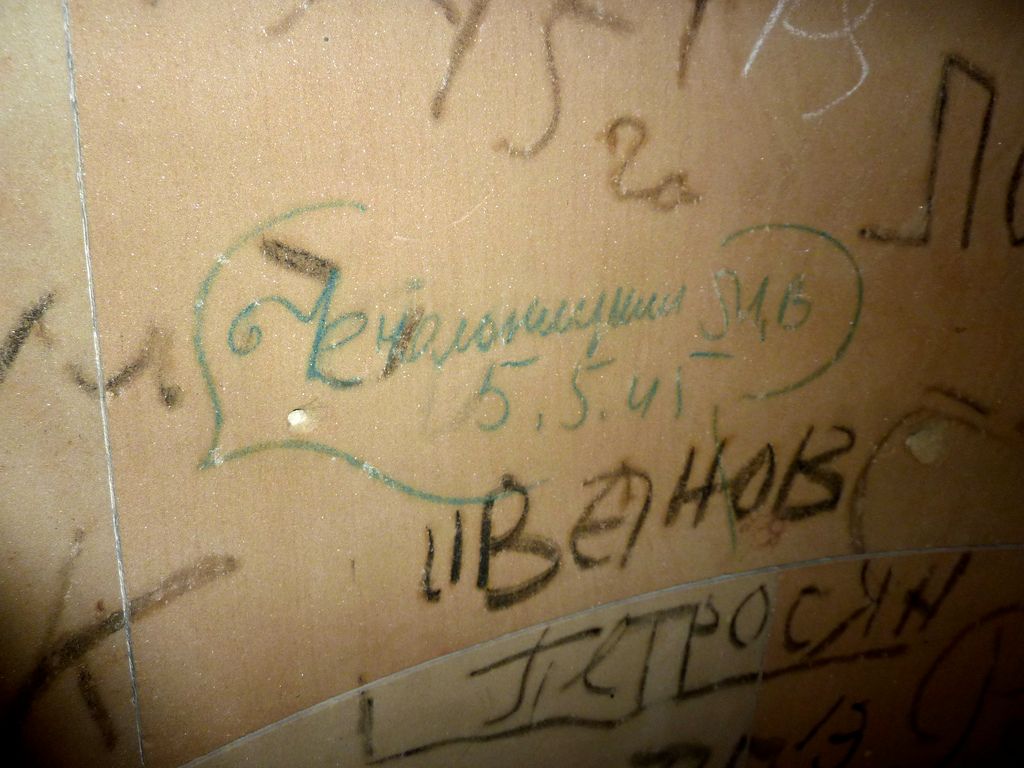

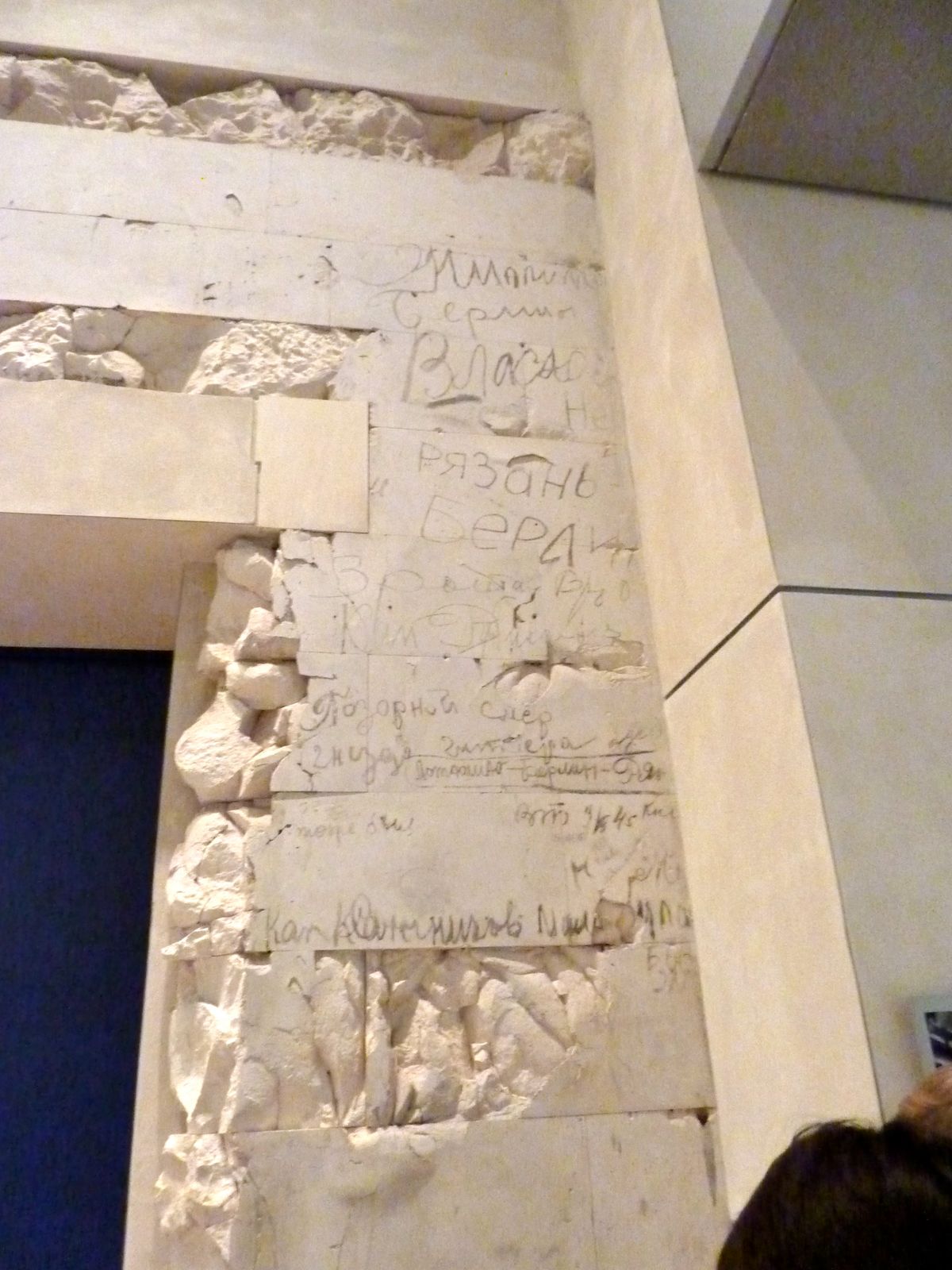

After that, many wandered the rubble-filled hallways taking in the destruction, and sometimes pausing to reach down, take a piece of the ever-present charred wood, and scratch something onto the walls. "A dream came true” wrote Afanassev. “Moscow-Smolensk-Berlin” recorded another. Approximately 95% of the graffiti are simply names: “Ivanov,” “Pyotr,” “Victor, ” etc.

Most of the graffiti was in Russian; a sooty word cloud of Cyrillic names, vulgarities and reflections. Other languages like Arabic can also be found in some places, reflecting the vast swath of territory that contributed manpower to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. “Bashkir” and “Groznyj” are two of the examples, referring to Bashkiria and Chechnya respectively.

The Soviet vandals' fingerprints on the Reichstag were largely forgotten about in the postwar period when shabby repair work covered up the interior damage with paneling. And that’s the way it stayed for half a century, until the reunified German nation set about restoring their capitol building for a post-Cold War future. In 1995 British Architect Norman Foster ripped out the paneling and was amazed to discover the text inscribed on the stone underneath. Foster was profoundly affected by the time machine-like power of the letters and he modified the architectural plans in order to preserve them.

Historical appreciation was far from unanimous, however. Politicians like newly elected Johannes Singhammer (later VP of the Bundestag) rejected the Soviet graffiti as hateful. “Death to the Germans,” and “The Russians were here and always beat the Germans,” are two notable examples.

The preservationist and self-confessional school of thought ended up prevailing inside the refurbished (and renamed) Bundestag, as it did all across Berlin. As then Parliamentary President Rita Süssmuth later told The Atlantic, “this makes us stronger, not weaker. It makes humanity stronger.” Today you can see the graffiti on publicly available tours of the Bundestag. (Though a few pieces of the most vulgar, truly unprintable bits have been scrubbed at the request of the Russian Embassy.)

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

June 27, 2017

Sources

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/07/the-graffiti-that-made-germany-better/373872/

- http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/was-die-russischen-graffiti-im-reichstag-bedeuten--und-warum-sie-bleiben-sollen-ich-war-hier-16382540

- http://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/reichstag-new-german-parliament/

- The Reichstag Burns, This Time With Hope, New York Times, 06 Mar 1999

- https://www.germany-visa.org/best-things-to-do-and-see-in-berlin/