A 2,000-Year History of Alarm Clocks

Before personal alarms, workers employed ‘knocker-uppers’ to bang on their doors.

A vintage alarm clock. (Photo: Public Domain)

Yi Xing was a bit of an overachiever. A mathematician, engineer, Buddhist monk and astronomer, Xing was asked to improve calendars in China. He took it one step further, building upon centuries of Chinese innovation to create an astronomical clock to which he gave the catchy name “Water-Driven Spherical Bird’s-Eye-View Map of the Heaven.”

The clock was slightly more complicated than the average timepiece today, measuring not only time but the distance of planets and stars. A water wheel turned gears in the clock, with puppet shows and gongs set to emerge at various times.

Dating to the year 725, Yi Xing’s ingenious version of an alarm clock is one of the world’s earliest recorded devices of that nature. Along with the water clock Plato used to wake himself up for his legendary dawn lectures in the 4th century BCE, it is evidence that humans have been looking for ways to rise on time for thousands of years.

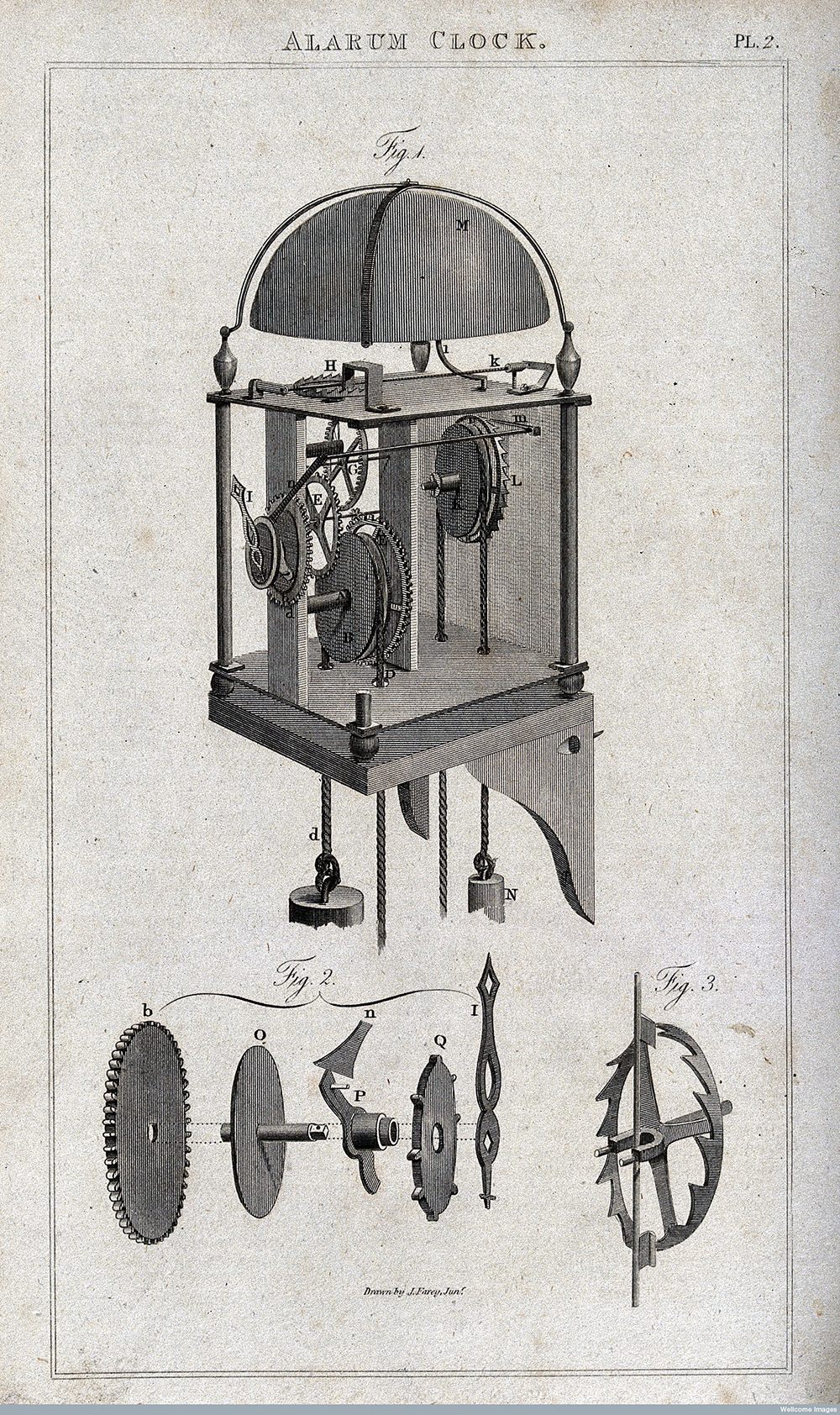

An engraving showing the mechanisms of an “alarum clock”, c. 1815. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

The idea was repeated by Europeans who created complex displays within chiming clocks in town squares. The next step was to make such clocks smaller, so they could be used individually. Historians believe personal mechanical alarm clocks originated in Germany in the 15th century, but their inventors are unknown. Most people didn’t own such clocks, though, and had to rely upon the sun, servants, or prayer-chiming bells. As work hours became more rigid, factory whistles were blown to encourage people living near their places of employ to get up.

The first known mechanical alarm clock inventor is Levi Hutchins, an American who in 1787 invented a personal alarm device to wake him at 4 a.m. He didn’t even have to be at work early, it was simply his “firm rule” to wake before sunrise. Though other alarm clocks existed previously, it seems Hutchins had not heard of them.

He wrote of his invention, “It was the idea of a clock that could sound an alarm that was difficult, not the execution of the idea. It was simplicity itself to arrange for the bell to sound at the predetermined hour.”

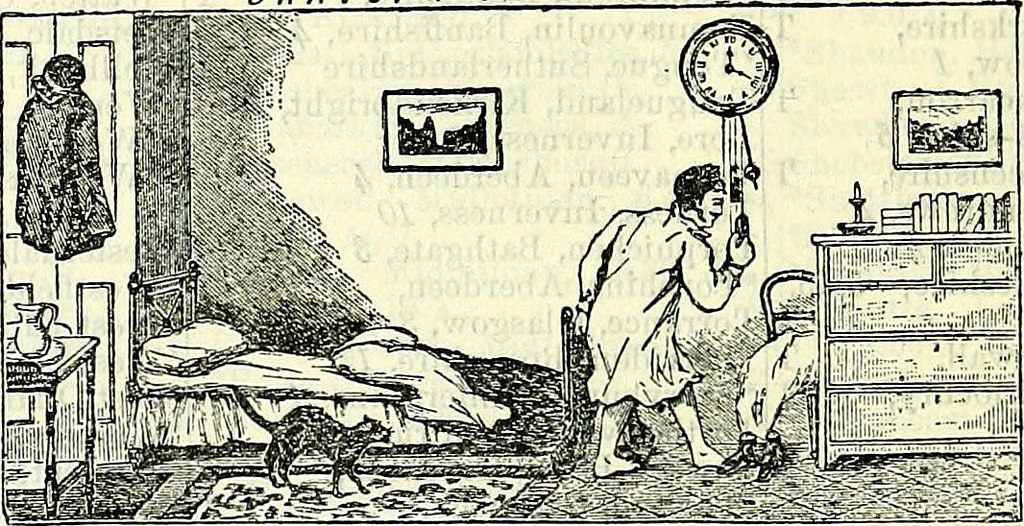

An illustration for an 1846 advertisement for a “double-action alarm clock”, which are “in daily use by postmen, policemen, railwaymen and others who have to get up early in the morning”. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

However Hutchins, more interested in morning rising than mercantile benefits, never patented his invention. Half a century later, Frenchman Antoine Redier became the first to patent an adjustable alarm clock, in 1847. The adjustable alarm clock allowed the user to set a time to awake, rather than being ruled by the dictates of others.

Each adjustable alarm clock had a hole in each number on the clock dial. A pin was placed in the hole responding to the time you needed to be up. Very simple, unless you wanted to be more specific than the closest hour!

Redier’s patent didn’t cross the oceans though, so American Seth E. Thomas got in on the action in 1876, patenting his own version. His eponymous company became a mass-producer of the alarm clock, bringing the invention to the masses.

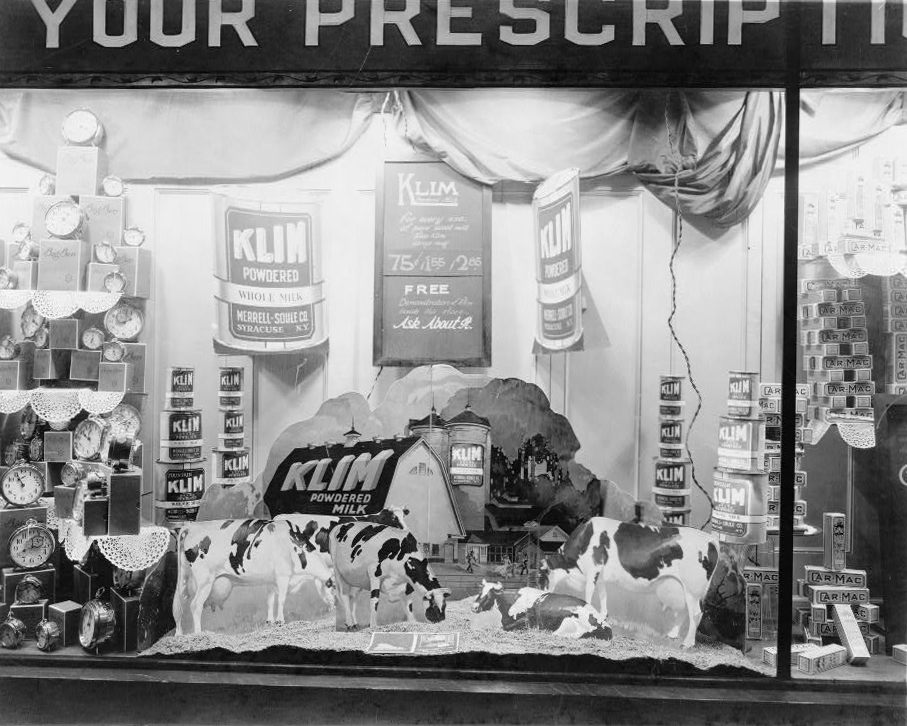

Alarm clocks on sale in Washington DC, along with powdered milk and toothpaste, early 1900s. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-117296)

“In an expanding urban and industrial world, people were obligated to know the time and to be on time,” writes historian Martin Levinson. “By the late nineteenth century, many consumers were actively seeking alarm clocks.”

Not everyone felt the need for a mechanical solution, though. Since the Industrial Revolution began, people had been finding ways to make sure they got to work on time. One popular method, at least in Britain and Ireland, involved hiring a knocker-upper. Using everything from a truncheon to a pea shooter, the knocker-upper would bang on doors and windows to wake those inside.

Often this service worked on a sort of subscription basis, with those being roused paying a few pence to the rouser. Everyone from old people to policemen got in on the action, with industrial towns hiring large numbers of knocker-uppers. By the 1920s however, as alarm clocks spread, the unique profession began to fade away.

During the mid 1900s alarm clock companies continued to innovate, with portable travel alarm clocks and radio alarm clocks that allowed consumers to wake up to something more compelling than a bell.

Then the Second World War began, putting the brakes on the alarm clock industry’s growth, as nearly all factories in the US and Britain were mandatorily converted into zones for war-related production. As war workers needed to wake up on time, too, both governments did allow some alarm clocks to be manufactured.

Three alarm clocks from the 1930s-1950s. (Photo: Siren-Com/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Metals were scarce at the time, though, so most war-clocks were made of a combination similar to a reinforced egg carton, with pulped paper and pressed wood. Nonetheless, they were still thin on the ground, with production levels almost six times lower than before the war began. Due to this decreased supply the U.S. War Production Board requested “that no one buy a war alarm unless it satisfies real need, not merely want, wish, or whim.”

The war may have limited production, but it couldn’t halt the passage of time forever–or the people who were worried about knowing what that time was. As the war dragged on and old alarm clocks began to break, pressure for greater supply increased. The government, recognizing that alarm clocks had become essential to the smooth running of industry, allowed some factories to re-commence selling their products. With factories back in business as early as 1944, alarm clocks soon became one of the first products to debut so-called post-war designs.

The alarm clock essential: the snooze button. (Photo: Sean McGrath/CC BY 2.0)

Enter, the snooze button. Popular opinion has it that the snooze was the feat, or fault, of Lew Wallace, the famous author of Ben-Hur. However, the Lew Wallace Museum asserts that Wallace could not have created the snooze button, although he did invent a few other things. Indeed, the author died in 1905, nearly a half-century before General Electric-Telechron made a clock with the snooze function. Nevertheless, the function quickly became popular and exists today as an essential part of alarm clocks.

These days the alarm clock, in its original form, is endangered, since alarm apps are now ubiquitous. In 2012, when UK carrier O2 surveyed their customers about the ways their smartphones replaced other devices, they found that the alarm clock was the most commonly replaced; 54 percent of O2’s smartphone customers had relegated their alarm clocks to the dustbin of history.

Though its form may change, its unlikely the alarm clock will ever go away. Or that you’ll ever get up without at least one snooze.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook