A Visit to India’s Last Colony of Magicians And Acrobats

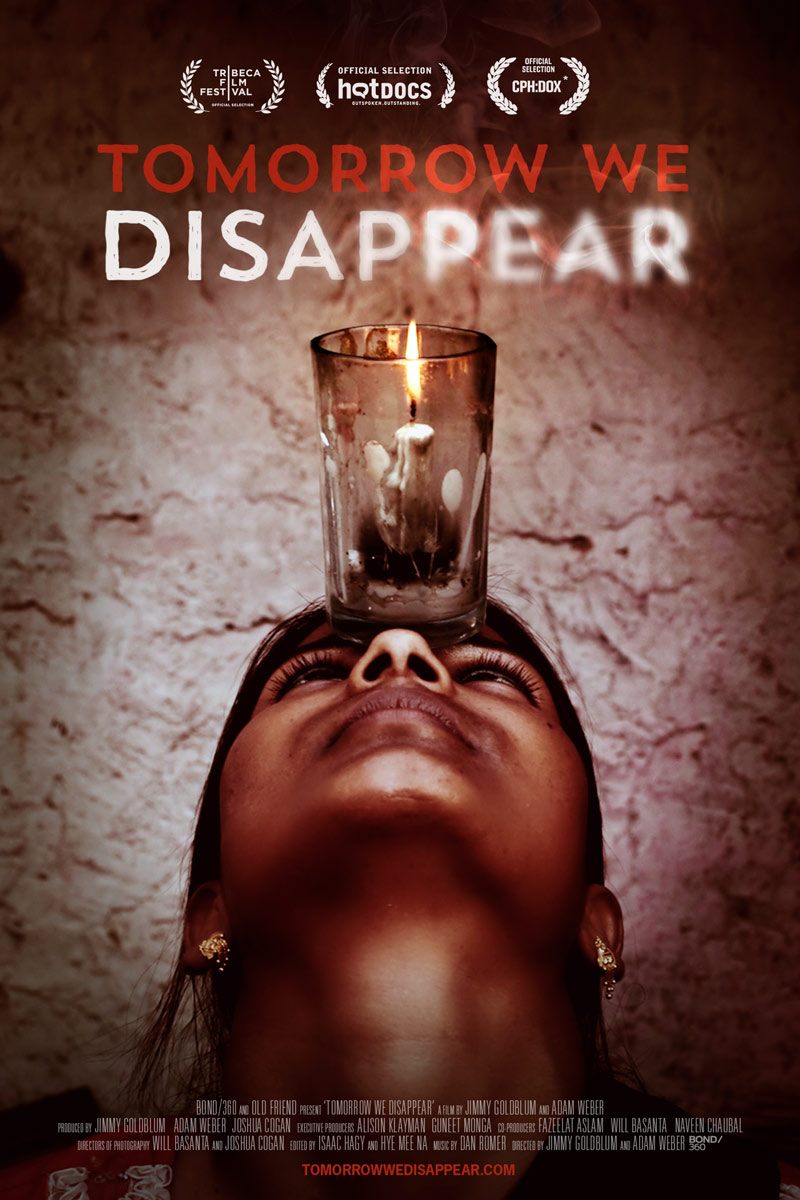

All images courtesy of BOND/360

The Kathputli colony, located on the outskirts of New Delhi, is where families of magicians, puppeteers, acrobats, and artists converge. Hand-built by the residents over decades, the colony is an outward expression of the performers’ unique culture, with practice spaces that allow them to perfect their craft.

For filmmakers Jimmy Goldblum and Adam Webber, the Kathputli colony is one of India’s most intriguing yet imperiled places. Since the 1950s, when roaming families of performers first settled in the area, the colony has become one of the country’s last bastions of magic and puppetry.

But as modernization arrives on Kathputli’s doorstep in the form of a luxury development proposal, the community’s entire way of life is threatened. Its culture is baked into the very structure of the colony, and, as the new documentary Tomorrow We Disappear shows, for them, adapting to a hyper-modern lifestyle is akin to fitting a square peg in a round hole.

At its core, Tomorrow We Disappear is a film about change. And it evokes the fear, resentment, and powerlessness the Kathputli residents feel when confronted with development schemes and inefficient governance.

We talked to Jimmy and Adam about the process of making Tomorrow We Disappear, which is available for streaming.

Besides this particular colony [Kathputli], are there still other places in India where these traditions survive, or is this sort of the last holdout?

Adam: What makes Kathputli unique is that they were all these separate itinerate groups of performers that would travel around for hundreds and hundreds of years. In the 1950s, they started using Kathputli as like a stopover tent camp outside of Delhi. But then Delhi started doubling, tripling, and quadrupling in size, so they started to hang around a little bit more, and they [the performers] stayed permanently.

So [Kathputli] is the first place that has this concentration and variety of different artists from so many places.

How did you get involved with this particular community? Where did the idea come from?

Adam: Jimmy and I were college roommates together, English majors actually. We read Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, and it’s this crazy, magical novel. At the end of the book, the main character hides in a “magician’s ghetto”—that’s the actual quote from the book, what the place was called. When Jimmy read it, he Googled “India Magician’s Ghetto” thinking, “what if this place actually did exist?”

Because so much of Midnight’s Children is fantasy.

Adam: Right. So he found this little blurb in the Times of India, and he emailed to me, and we both got really excited about it. But we searched, and still couldn’t find that much information about it.

At the moment, it was kind of “well, we have two options–we could just quit our jobs, and fly there. Or leave it be.”

So we quit our jobs and flew there. It was a crazy, impulsive time. The book [Midnight’s Children] was really close to both of us, so we decided to go in search of it.

And it’s such a fascinating story. Beyond what’s going on politically, just watching the acrobats and magicians do their thing is pretty crazy. How was it to film some of the scenes–where you saw teenage girls bending metal rods with their neck?

Jimmy: To step outside of the film for a second, the way that worked is: we went and met with Maya, and she’s a very pretty 19-year-old girl. And we heard rumors that she was the most talented acrobat in the colony, and we walked in and she’s just this very petite girl, and we were like, “What is this?”

Her English was choppy, so she ended up just handing Adam that piece of metal rebar you saw in the film. And she asked him in sort of broken English to bend it. Because she’s pretty, he obviously wanted to impress her, and he just tried with all his might to make a dent in this thing. He turned bright, bright red, he couldn’t do anything.

And then the cameras turn on, and that’s when she puts it down, and puts it against her neck. And using her chest, she’s just able to lean forward and bend it into a perfect U.

So you could imagine from our perspective, we’re like, “This girl is a superhero.”

Some of the things they do are pretty unbelievable. So you have to think that these men and women spend a huge chunk of their lives learning how to do their tricks safely.

Jimmy: Well, no, actually. Maya [the girl who bent the rebar] has broken something like 12 bones.

Adam: And she punctured her neck.

Jimmy: In the movie, you see her scar. Look, we’re not saying that this place is a child safety hazard by any means. What it is, is that kids are just trusted to be really brave, and encouraged to brave–and that obviously causes a lot of injuries early on, so later in life they know exactly what they’re doing, and are skilled at a level that you probably couldn’t reach in the West, because our safety precautions would never allow it.

One of the scenes I wanted to discuss was when the community members go to the courthouse [to file an anti-development petition], and they all cram into the elevator and the door keeps opening. I thought that was a cool metaphor for how their lifestyle isn’t made for that hyper-modern existence.

Jimmy: It’s like any sort of redevelopment scheme. Like, okay, we’re going to take this slum and redevelop it into luxury skyscrapers, and we’re also going to create housing for the people we’re displacing, but that housing is going to be very different.

If you grow up making traditional wood fires, moving into a modern development is not going to work for you. People obviously adapt, but within reason. I mean, they go to the courthouse to petition against the developers, and they can’t even get upstairs because the elevator won’t work.

It’s a perfect encapsulation of the problem. The culture is really entrenched in the architecture of this colony. It was hand-built by the artists to create and preserve their traditional art forms. And so to take them out of that context, and put them into something that’s four walls, 10-by-10, the culture won’t naturally move with it.

We take modern conveniences for granted–they make our lives easier. But when you don’t grow up with them, it’s just so foreign, right?

Jimmy: A lot of our characters would say to us, “you have to give up something, to get something.” And you can’t just put people in a new development, and not expect that to take away something. If the Indian government is trying to eradicate slums, and construct modern cities, then things will be inevitably lost in that process.

A lot of the film is about trying to showcase what’s at stake–what will be lost.

Jimmy: We really didn’t want to create some expert, ‘talking-heads contextualizing modern Indian development.’ We really wanted to create an intimate portrait of artists in India who represent a traditional culture that’s losing their way of life. And to establish that intimacy, you really have to earn people’s trust, and spend the time.

Adam: That’s actually a really important point. Just to get at the approach for the movie, we wrestled with it a lot. The film you saw came out of a lot of intense discussion. After interviews and research and all this groundwork we put into it, we didn’t think in these people’s cases they didn’t need another top-down telling you about development statistics. It was really important for us to have a bottom up view of what this displacement process was actually like, because a lot of it gets lost in the news headlines.

For us, the purpose of the film is to show what is the experience like when this is happening to you. What does it feel like? It’s really confusing, and it’s scary. The questions are more intimidating than the actual thing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook