An Adorable Swedish Tradition Has Its Roots in Human Experimentation

How the Swedish custom of lördagsgodis, or Saturday candy, relates to tests at a 1940s mental institution.

In 1946, at a mental hospital outside of Lund, Sweden, researchers forced a group of patients to ingest 24 pieces of a sticky, light brown substance in a single day. These severely disabled patients were involuntary participants in a long-term study commissioned by the state medical board in cooperation with big industry, and this coerced feeding would continue for three years. The four to six doses that they consumed four times a day over that time were in some ways sweeter than their typical medicines—but also more troubling. No benefit to the patient was ever expected. Rather, the goal was to measure the damage inflicted by the substance over time and determine a dosage safe for public consumption.

The ruinous “treatment” in question was a caramel candy. The corporate underwriters were sugar, chocolate, and candy companies. And the effects of the so-called Vipeholm experiments still reverberate today. In fact, one direct result has become a lasting—even beloved—part of Swedish culture.

In Sweden, Saturday is for sweets. The Swedish custom of lördagsgodis, or Saturday candy, was spurred by the outcomes at Vipeholm, which definitively proved that sugar, particularly between meals, causes tooth decay. The idea behind lördagsgodis is moderation—to limit candy consumption to a weekly, rather than a daily, occurrence.

Once a week, Swedes are given a free pass to indulge in all the gummies, chocolates, and salty liquorice their Nordic hearts desire. (Non-Nordic hearts will most likely take a pass on the salty liquorice.) However, few Swedes standing in line at the supermarket to collect pick-and-mix candy on Saturday morning know that their weekly indulgence has its origins in the sustained mistreatment of 660 psychiatric patients.

Before the Vipeholm experiments, the cause of tooth decay had been a topic of much speculation. People blamed their dental woes on everything from wine and hot foods to masturbation and vitamin deficiency, writes Samira Kawash in her book, Candy: A Century of Panic and Pleasure. By 1938, leading scientists around the world were pointing to either too many carbohydrates or a lack of various vitamins as the source of dental cavities. But there was no definitive proof.

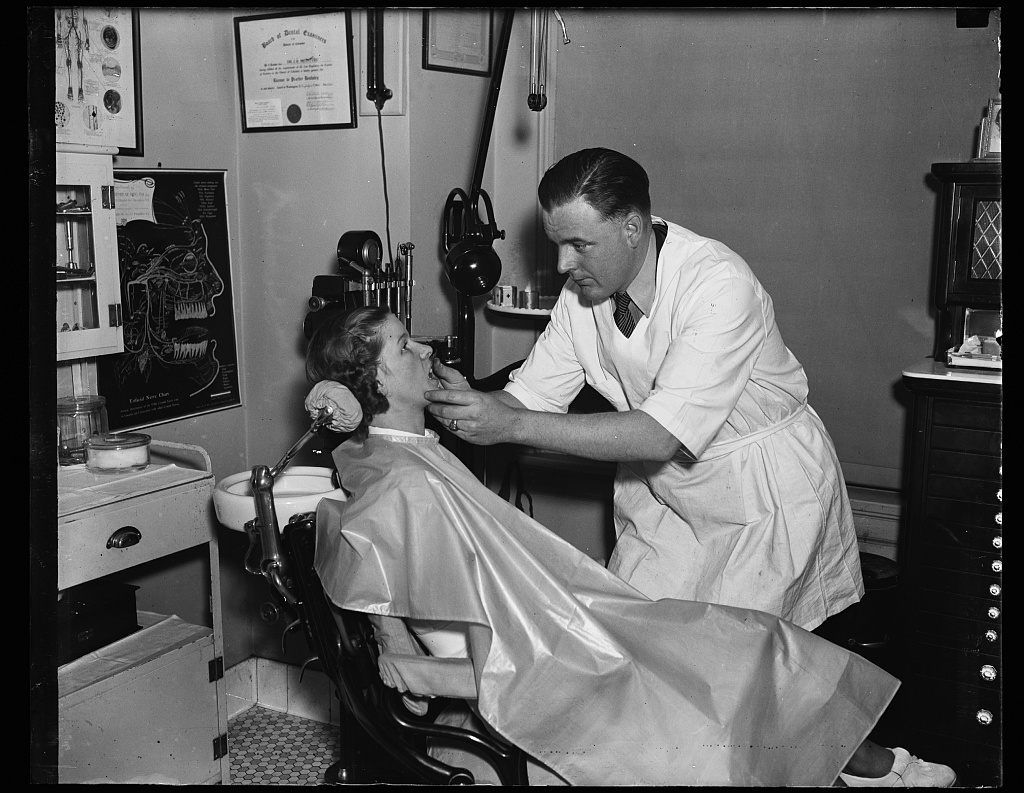

What was evident, however, was that the Swedes were in serious need of a dental intervention. A study carried out in the 1930s showed that three-year-olds there had cavities in a whopping 83 percent of their teeth, notes Bo Krasse in a paper in the Journal of Dental Research. New laws mandated that municipalities provide dental care to citizens, but there were not enough dentists to meet demand. So a decision was made to shift over to a prevention-focused model, a better use of resources than long waiting lists at doctors’ offices. Problem was, no one knew how to prevent tooth decay yet.

In search of clarity, Sweden’s national medical board decided to undertake a long-term nutritional study to determine the root cause of dental cavities once and for all. The most desirable, accurate study, it was determined, would test human subjects. In an ideal test, one would have human subjects whose vital signs could be monitored daily, who would follow a drug or dietary regime without fail, and whose environment could be totally controlled by the researchers.

But where would one find such subjects? For the medical board, the answer was obvious. They had jurisdiction over the state mental institutions.

Of the four state mental institutions in operation at the time, Vipeholm was perhaps the bleakest. It housed the cases deemed fully “uneducable.” Many patients could not dress themselves. Many were tied to their beds. The doors of the hospital were locked at all times and the only private bedroom was an isolation chamber without any furniture, where patients in solitary slept on a bed bolted to the middle of the floor. At mealtimes, there were no knives or forks, only spoons.

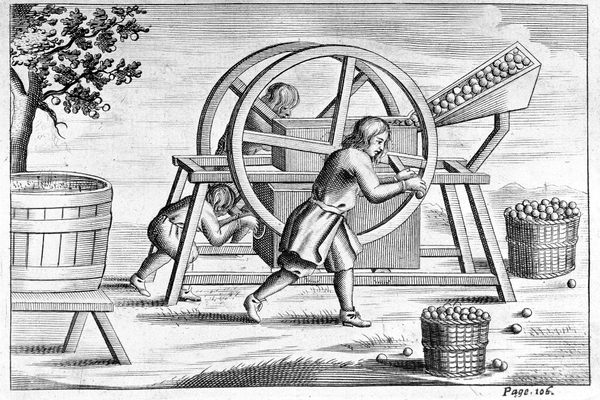

After an initial study focused on vitamins, the infamous Carbohydrate Study began in 1946. The 660 Vipeholm patients were chosen to undergo variations on extreme sugar consumption. One group consumed sugar in a solution, one group consumed sugary bread at meals, and the last group consumed special toffees between meals. The caramels had been specially formulated for stickiness, so that they would cling to teeth and gums. When the study ended, 50 of the research subjects had completely ruined teeth.

The Vipeholm study was a success insofar as it positively identified a link between sugar consumption and tooth decay. It was also reprehensible. It was the relative helplessness and immobility of the patients that made them attractive test subjects. In the dogged pursuit of a healthier society, the powers that be sacrificed the health of society’s most vulnerable members.

The Swedes were hardly alone in pursuing highly questionable controlled human experiments at this time. For example, the United States injected radioactive substances into otherwise healthy living subjects as part of the Manhattan Project. And, of course, concurrent to the Vipeholm experiments in Sweden, experimentation on human subjects was reaching its odious zenith in the Third Reich, with prisoners in Nazi concentration camps subjected to some tests so innately depraved that they qualify mostly as blood sport.

In 1947, following the revelations of these practices in the camps, the Counsel for War Crimes adopted the Nuremberg Code, which laid out a comprehensive set of medical and scientific ethics, including the principles of informed consent and nonmaleficence (or “do no harm”). These principles would later be incorporated into the Declaration of Helsinki, the current defining, international document on modern research ethics.

The lasting legacy of Vipeholm, however, turned out to be something a bit sweeter—Saturday candy. In 1957, following publication of the Vipeholm study’s results, a coordinated public health campaign kicked into gear. Radio PSAs, home-delivered pamphlets, and posters in waiting rooms encouraged young Swedes to brush their teeth and eat less sweets. The new message around candy was not prohibition, but moderation. The mantra was “All the sweets you like, but only once a week!”

Even today, you would be hard-pressed to find a Swedish child whose face doesn’t light up at the news that Saturday has arrived. Indeed, data implies that Swedish adults are equally excited. Swedes, it turns out, love candy. They consume more candy per capita than almost anyone else. And annoyingly, they do so while maintaining one of of the highest levels of dental health in the world.

Generations of good teeth and a twee tradition of Saturday sweets are surely the coziest possible outcome of the dark days at Vipeholm. But looking back, it’s hard to sweeten the pill.

Update, 1/4: An earlier version of this story identified the Carbohydrate Study at Vipeholm as occurring during WWII. While experimentation at Vipeholm began in 1945, the Carbohydrate Study began in 1946, after the war’s end. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook