In Ancient Egypt, the Duat Was a Netherworld of Gods and Monsters

A guide called the Amduat helped pharaohs navigate the complex afterlife.

Each week in October, University of Manchester Egyptologist Nicky Nielsen will share an intriguing aspect of ancient Egyptian beliefs and traditions surrounding death and the afterlife.

On the morning of Oct. 16, 1817, Italian explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni entered a narrow rock-cut fissure in the Valley of the Kings. As he navigated a long, sloping passageway, the light of Belzoni’s torch illuminated beautiful and, to the Italian, strange symbols covering both walls and ceiling. He had found the tomb of the Egyptian king Seti I (1323-1279 BC). “I may call this a fortunate day,” Belzoni would later write. “One of the best, perhaps, of my life.”

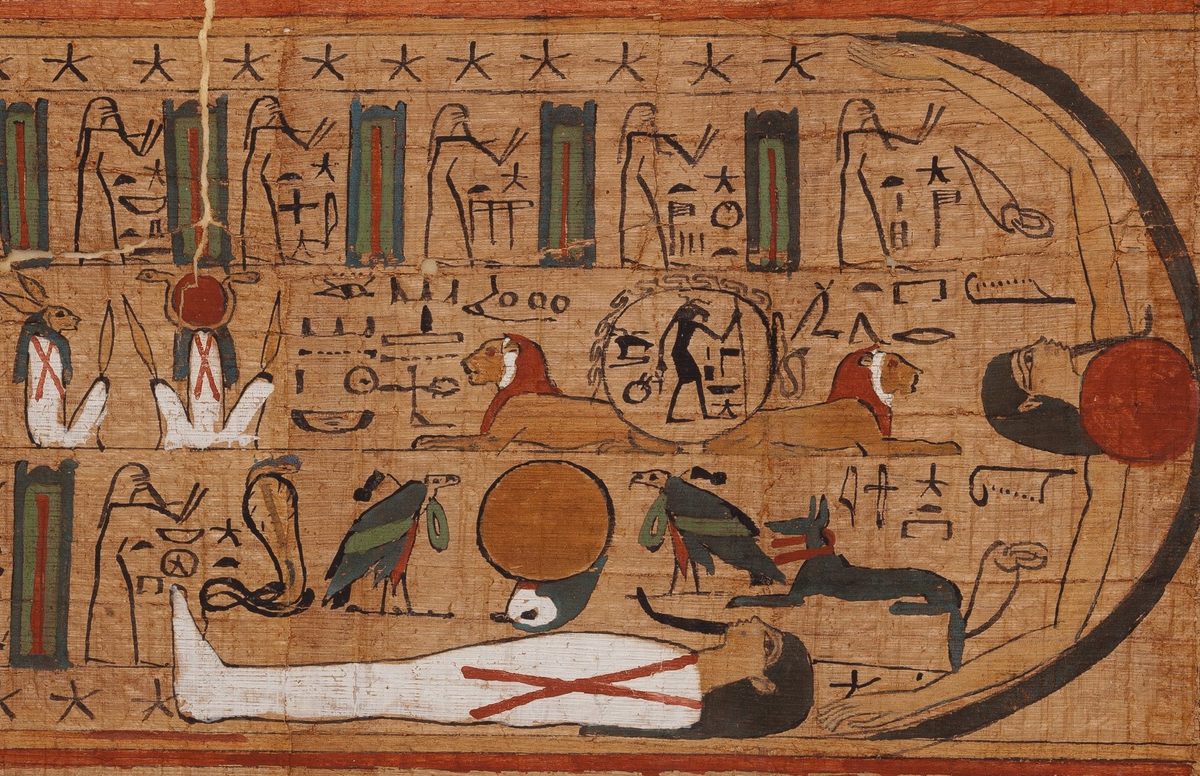

In the very heart of the tomb, in the burial chamber of the king, Belzoni found what would later be recognized as one of the most detailed descriptions of the invisible world beyond the veil, the realm which the Egyptian pharaohs wished with all their might to reach. This lengthy funerary text, also found in several other royal tombs, is known to modern scholars as the Amduat, a name which comes from the ancient Egyptian term imy-dwat, meaning “that which is in the Duat, or netherworld.” The Duat was mysterious and dangerous, even for pharaohs armed with the knowledge contained in the Amduat. Today, it’s a fascinating place to explore. I’ll be your guide to navigating this world.

In Egypt’s Pharaonic civilization, which lasted more than 3,200 years, there was no single, static concept of the afterlife. Rather, visions of the afterlife and the journey of the soul after death changed and evolved, some applying to all the people of the Nile Valley, others only to the ruling monarch. A typical royal tomb of the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC) included many different descriptions of the afterlife. Some, like the Book of the Dead, contained spells and utterances that allowed the deceased king to pass safely through the judgement of the dead. Others, such as the Book of the Heavenly Cow, contained descriptions of the sky and the deities found within it.

The Amduat, by contrast, served as a metaphorical map of the netherworld and a description of the sun god Ra’s passage through this ethereal realm each night during the twelve hours of darkness. It was crucial for the dead king to know the names of the allies and enemies that dwelt in that shadow realm, as the royal soul also would pass through it after death.

To the ancient Egyptians, the sun god traversed the sky in a great barque, which carried both the god and his retinue. As the sun set on the western horizon, throwing orange flames across the foothills of the desert, the barque would plunge into the dark chasms of the netherworld, arriving first in a marshy and fecund land, filled with stagnant ponds and reeds, known as the Waters of Osiris.

After passing through these peaceful waters, the barque of the sun god would strike a far unfriendlier shore: By the fourth hour of the night, the barque reached Rostau, the vast desert realm of the falcon god Sokar, where the boat was borne by snakes rather than sailing of its own volition. Passing into this realm of danger and desiccation, the sun god came to a colossal pyramid enclosed by a lake of fire. Magical protections guarded the monument, cast by two birds perched atop it. The birds were Isis and Nephthys, the wife and sister of the mighty Osiris, ruler of the dead, whose body lay entombed inside the pyramid.

In the darkest hour of the night, the soul of the sun god would merge with the soul of Osiris, beginning the process of regeneration and rebirth that would eventually see the sun ascend again from the eastern horizon and bless the living world with light.

After this pivotal moment, the sun god continued his journey, but soon found himself under attack from enemies and demons. Chief among these was Apophis, a monstrous serpent who lay in wait to destroy the weakened sun god and cast the universe into eternal darkness. Fortunately, the sun god did not stand alone. The sun god travelled with a retinue of minor gods who could use their magic to chain and bind Apophis, stopping his malevolent attacks.

As the enemies of Ra were cast down, beheaded, burnt, and destroyed, the barque of the sun god could safely pass from the sandy shores of Rostau into the primaeval waters of the oldest god, Nun, the source of all creation. The rebirth of the sun god was completed when he immersed himself in these life-giving waters, and as the first tendrils of dawn played across the eastern horizon, his long journey was complete—until night came again.

The king, when undertaking this same journey through the netherworld after death, would repeat the magical spells of the Amduat, carved on the walls of his burial chamber, to follow in Ra’s footsteps and pass safely through it. After dodging the dangers of the Duat, the soul of the king was united with Osiris, the Ruler of the Justified Dead. Unlike the sungod, the king’s soul would not arise again in the morning, but remain as one with Osiris. In this way, the king who had ruled on earth would continue to rule in the afterlife.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook