The Anti-Waiter Sentiment That Made Automat Restaurants Go Mainstream

The “waiterless” restaurants that weren’t.

People in the late 1800s really did not like waiters. Though waiters were still a novelty—they sprung up with the rise of the restaurant earlier that century—they had come to be regarded as a burden to service and, especially in the United States, were assailed for their unpleasantness.

Channeling this resentment, an 1885 New York Times editorial claimed that servers in restaurants were “one of the necessary evils of an advanced civilization” and noted that “the only occasion when a gentleman was excusable for using profanity in the presence of ladies was when it became necessary to blaspheme concerning the dereliction of waiters.” This is because waiters represented a special kind of annoyance: in a restaurant, a customer is “preyed upon by the thought that [his waiter] is hovering over him, watching his every movement, and ready to ‘size him up’ in proportion to the amount of his order.”

Another driver of the anti-waiter sentiment was the expectation of tipping, a European import that was maligned in the United States as “offensively un-American.” Because waiters were already viewed as a strain on customers, the prospect of tipping them was outrageous.

A popular 1916 book, The Itching Palm: A Study of the Habit of Tipping in America, noted that “the gift of a quarter to a waiter as a tip is an unsound transaction because the patron receives nothing in return—nothing of like substantiality.” Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1913 said tipping was “a gross and offensive caricature of mercy… it curses him that gives and him that takes,” and as far back as 1877, the New York Times lamented, “When the waiter rushes forward to take your coat, hang it up, drag out your chair … for this wonderful galvanization of the waiter, what does it mean? Merely that he considers it probable, nay certain, that some of the silver change in your pocket will be transferred to his.”

By 1926, the “waiter” brand had in some circles grown so toxic that one organization—the United Restaurant Owners Association of New York—called for a new label: “the term ‘waiter’ has taken on a menial significance,” they said, because few people recognize the “skill and even artistry necessary” for the job.

By then, it was too late. Many people were already through with what one newspaper later memorialized as the “testy servant problem,” and they wanted waiters gone.

Beginning in the late 1800s, restaurants went to great lengths to develop “waiterless” systems to please their customers. These mostly failed attempts tried replacing waiters with a mix of conveyer belts, dumbwaiters in the centers of tables, and—in one particularly odd case—500 mini electric cars.

In 1896, German engineer Max Sielaff, the inventor of the vending machine, teamed up with a candy company to open the most enduring such waiterless restaurant: the Automat.

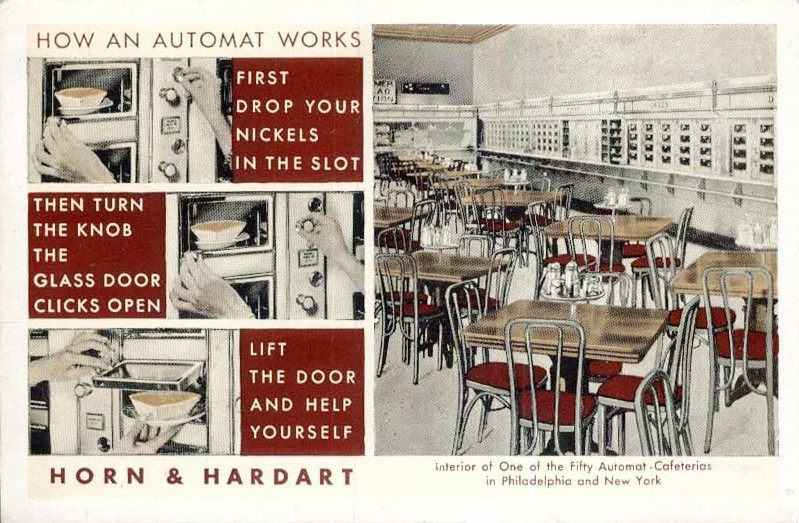

The way Automats worked was simple. The walls inside each store were lined with a series of small windows, each of which contained an item of food. Customers inserted a coin, and the window unlocked, allowing them to pull out a meal. There were no waiters, no tips, and food came fast.

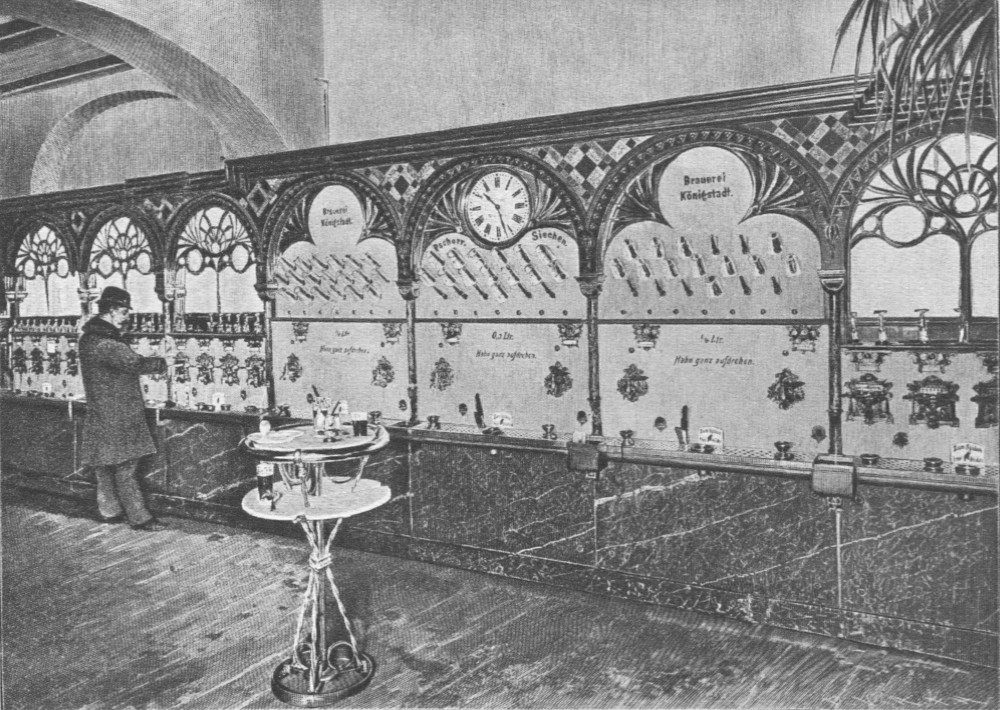

The first Automat, which opened in Berlin as an extension of Sielaff’s increasingly ubiquitous vending machines, featured a lavish dining room complete with stained glass windows. The place was a hit.

Besides a contempt for servers, the invention of the Automat was also about making restaurants more efficient in an increasingly fast-paced and industrialized culture. This was especially true in Germany, where the anti-waiter sentiment does not seem to have been as strong. But in the United States, it was a different story.

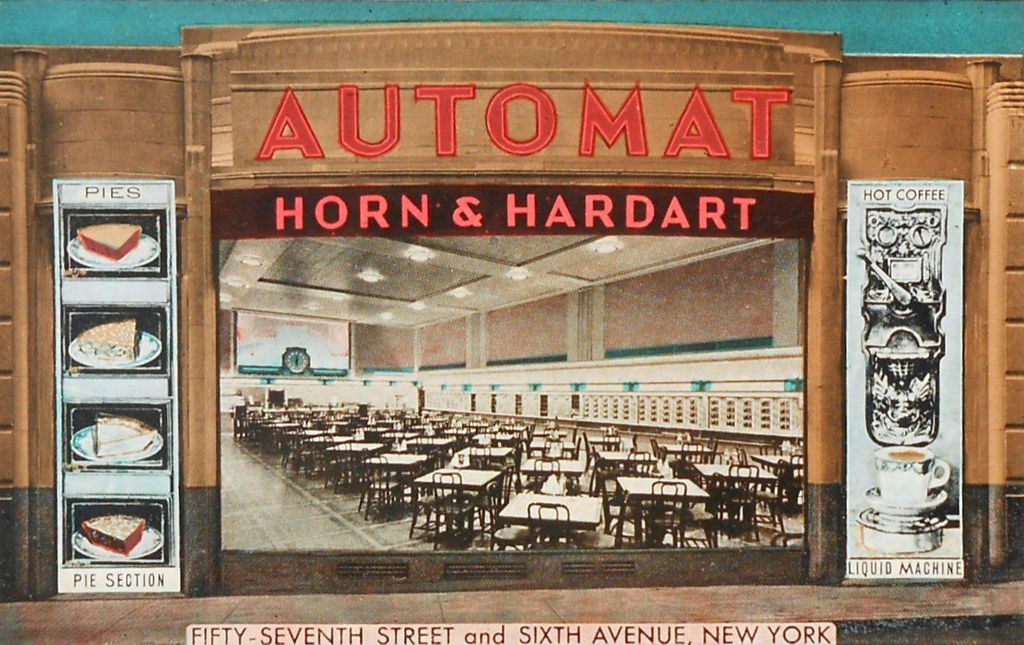

The success of Sielaff’s Automat drew the attention of Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart, a business duo that owned quick-serve lunch counters in Philadelphia, and they purchased the technology. Horn & Hardart bet that Americans would flock to this new style of waiter- and tip-free restaurant.

They were right.

In June 1902, Horn & Hardart debuted their first Automat in Philadelphia. It became an immediate sensation, and by 1912, they expanded into New York City, unveiling a two-story location in Times Square to an enthralled crowd. Horn & Hardart Automats expanded especially rapidly during the Great Depression, when their cheap and quickly prepared food was in high demand. One woman remembered Automat customers “pouring free ketchup into glasses of free water and drinking a Depression cocktail.”

By 1927, there were 15 Automats in New York City. Around World War II, at the height of the Automat’s popularity, Horn & Hardart had over 80 locations in Philadelphia and New York. They were serving 350,000 customers per day.

To an American public tired of dealing with—and tipping—waiters, Automats were a revolution. But the essential irony is that these restaurants were anything but automatic. According to Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville, “while automats were hailed by the thrifty populace as being ‘waiter-free’ and—even more appealing—‘tip free,’ someone had to cook the food, stock the little compartments, keep the floors clean, bus the tables, refill the sugar and condiments,” among other responsibilities.

In New York, thousands of Automat employees prepared meals in a secret kitchen, then slipped them on to a “rotating pivot… into which was carved a series of open slots for food.” Once a customer grabbed an item of food from one of the Automat’s windows, the pivot rotated, and another item took its place in the window.

In the original Automat in Berlin, only cold foods like sandwiches were stocked in the windows. If customers wanted something hot, an employee would receive the order through a labeled compartment, make the food, and then lift it into a compartment for the customer to take. It was like waiter service—but with a wall in between.

Yet customers were so enthralled by the idea of an automatic restaurant that they often failed to understand that these “waiterless” eateries were staffed by waiters in all but name. In 1917, when 300 Automat employees went on strike for better wages, the New York public was baffled, and a New York Sun article labeled the Automat worker strike “the Strike Invisible.”

In the end, the existence of a large staff may not have mattered. By the middle of the 20th century, the wave of anti-waiter hysteria that catapulted Automats to prominence seems to have dissipated. Around the same time, Automats were losing their ubiquity as other, more convenient fast-food restaurants—like McDonald’s—began cropping up. But though the last Horn & Hardart Automat closed in 1991, anti-waiter sentiment hasn’t faded completely: just read Yelp reviews.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook