Bibliomania, the Dark Desire For Books That Infected Europe in the 1800s

Book lovers and collectors feared becoming a victim of the pseudo-illness.

Dr. Alois Pichler was almost always surrounded by books. In 1869, Pichler, originally from Bavaria, became the so-called “extraordinary librarian” of the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg, Russia, a prestigious position that gave him a salary three times higher than the average librarian: 3,000 rubles.

While many librarians have a deep appreciation for books, Pichler was afflicted with a specific irrepressible illness. A few months after Pichler took his position at the library, the staff discovered that an alarming number of books were disappearing from the collection. They suspected theft. Guards noticed that Pichler had been acting strangely—dropping books by the exit and hurriedly returning them to the shelves, refusing to remove his large overcoat, leaving the library several times within a day—and started paying close attention to him.

On March, 1871, over 4,500 stolen library books on everything from perfume making to theology were found in his possession, Pichler committing the largest known library theft on record.

Pichler was put on trial, where his lawyer alleged that the librarian was not in control of his behavior, explains Mary Stuart in the journal Libraries & Culture. He was influenced by a “peculiar mental condition, a mania not in the legal or medical sense, but in the ordinary sense of a violent, irresistible, unconquerable passion,” writes Stuart. This defense was designed to mitigate his punishment, but it didn’t work.

Pichler, who was found guilty and exiled to Siberia, was a victim of “bibliomania,” a dark pseudo-psychological illness that swept through the upper classes in Europe and England during the 1800s. Symptoms included a frenzy for culling and hunting down first editions, rare copies, books of certain sizes or printed on specific paper.

“Any obsession can become real disease,” says David Fernández, rare book librarian at Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto. “One of the aspects that can really be an issue is the financial aspect, even back then.”

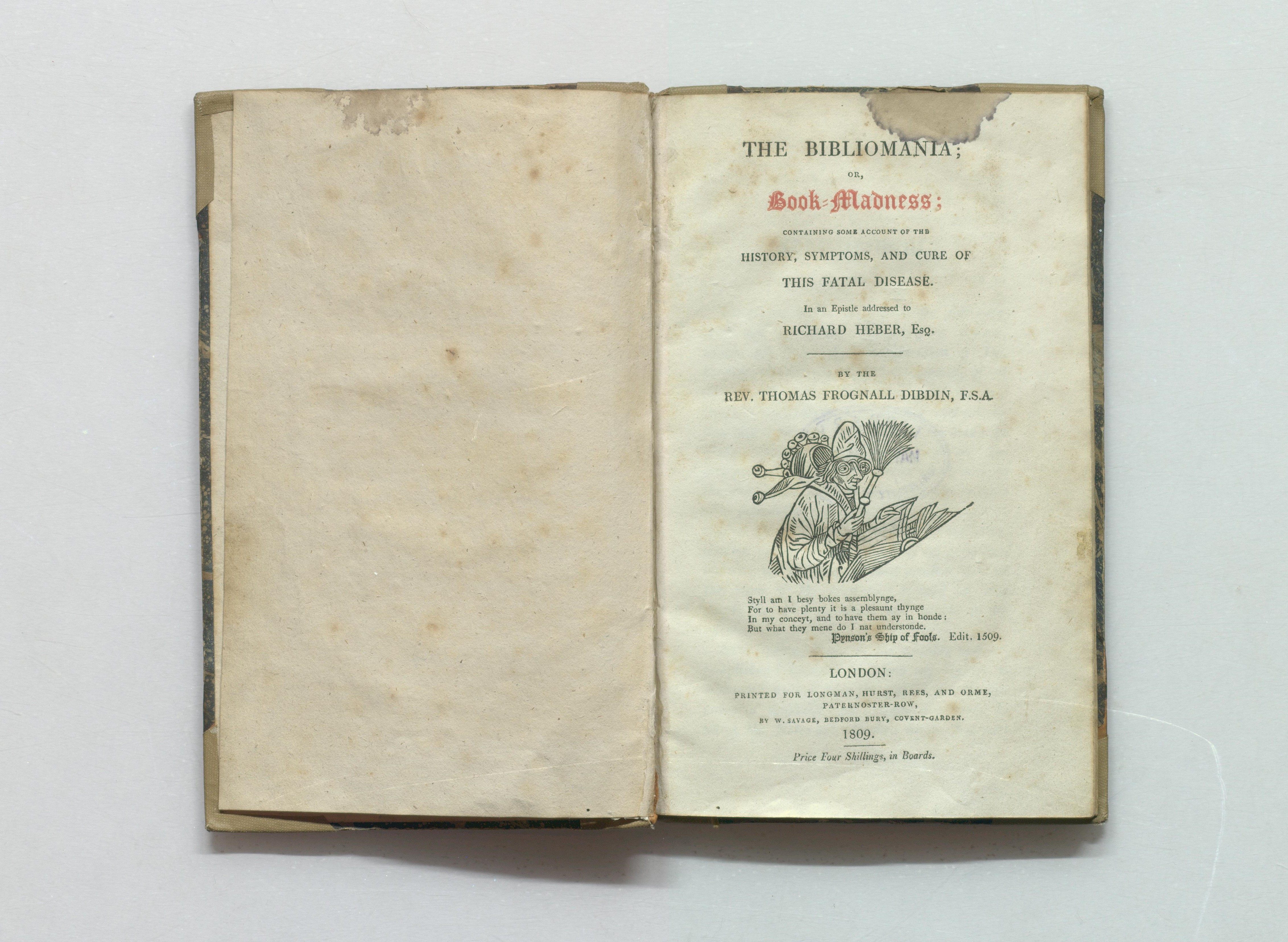

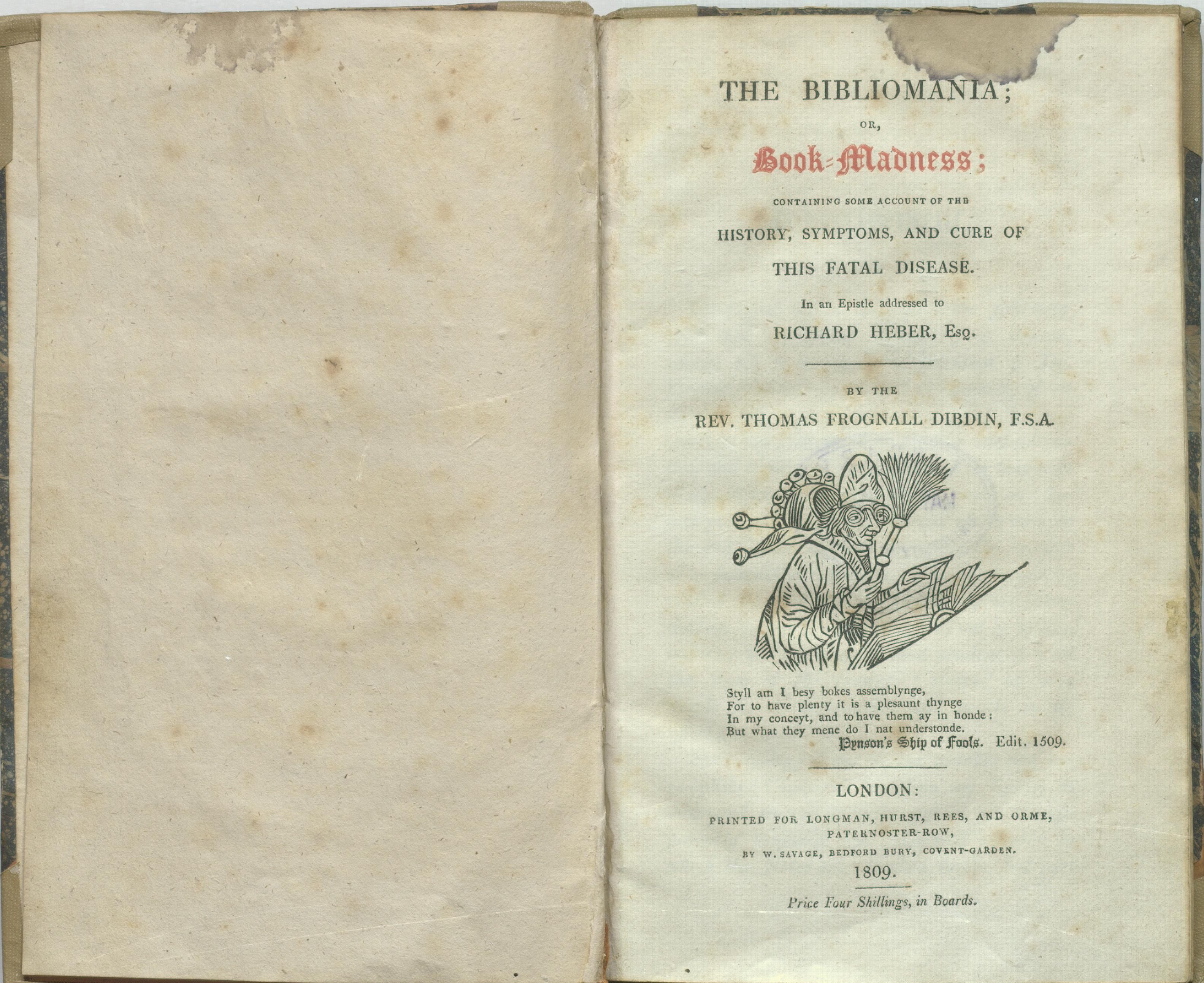

The social elite and scholars did everything they could to obtain and collect books—no matter the price. Some collectors spent their entire fortunes to build their personal libraries. While it was never medically classified, people in the 1800s truly feared bibliomania. There are several written accounts, fictional and real, of bibliomania, but the most famous and bizarre documentation is by Reverend Thomas Frognell Dibdin, an English book lover and victim of the neurosis. In 1809 he published Bibliomania; or Book Madness, a series of strange, rambling fictional dialogues based on conversations and real collectors Dibdin had encountered.

“I think a very good word to describe the book is that it’s very bizarre,” says Fernández, who has studied his library’s preserved copy of the 1809 first edition. “It’s a product of the generation in which it appears.” On the title page of the book, an engraving depicts a “book fool,” a character originally featured in the 1498 book, Ship of Fools, the first work of fiction to reference the discovery of the new world. That character is described as a vain book collector, the story touching on madness among scholars and collectors, explains Fernández.

According to Reverend Dibdin, the “book-plague” had reached its height in Paris and London in 1789. After the French Revolution in 1799, French aristocrats sold their estates to flee from the country and many private libraries emptied their shelves. Auction catalogs in the 18th century were teeming with French books, explains Fernández. Prices of fine antiquarian texts at least quadrupled in this period, wrote Philip Connell in the journal Representations.

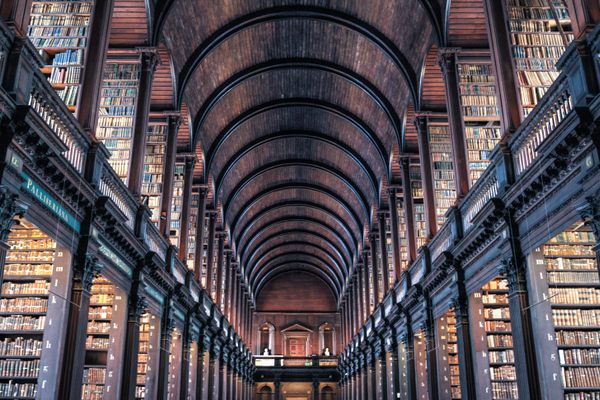

Men and some women collectors purchased books to conserve and preserve Europe’s literary heritage, while others did so as a symbol of wealth and power. At this time, constructing books was a delicate and laborious art completed by hand—from cutting the paper to creating the binding—which added value.

Then as now, collectors desired certain books for highly specific reasons—like the typefaces they used. One favored calligraphic style was known as “black letter.” Scottish poet and writer Robert Pearse Gillies recorded in his 1851 memoir: “There had sprung up a kind of mania for purchasing black letter volumes, although the purchasers themselves, from year’s end to year’s end, did not read, far less write, fifty pages consecutively.”

Then, there was the group of collectors who wanted books for the mere lust of possession. In Bibliomania; or Book Madness, Dibdin describes the symptoms of bibliomania, dramatizing a rather convincing make-believe pathology. He even uses medical language as if it were an actual malady. Dibdin points out eight particular types of books that collectors obsessed over: first editions, true editions, black letter printed books, large paper copies; uncut books with edges that are not sheared by binder’s tools; illustrated copies; unique copies with morocco binding or silk lining; and copies printed on vellum.

In addition to his book collecting and writing, the Reverend founded the Roxburghe Club of book lovers, which became known for secondhand book trading that defined and propagated bibliomania. “Dibdin was the most notorious diagnostician—and indeed victim—of the bibliophilic neurosis afflicting the British upper classes in the Romantic period,” writes Connell.

While others wrote books about bibliomania, including Gustave Flaubert’s Bibliomanie, which dramatized the legendary Spanish monk biblio-criminal who murdered a rival bookseller, Dibdin’s remains the pivotal piece that provided commentary on the time period. “It is the seminal work in the history of book collecting,” says Fernández. “It’s satirical, but not to the point of being humorous. It’s more like a critical reading of the notion of collecting.”

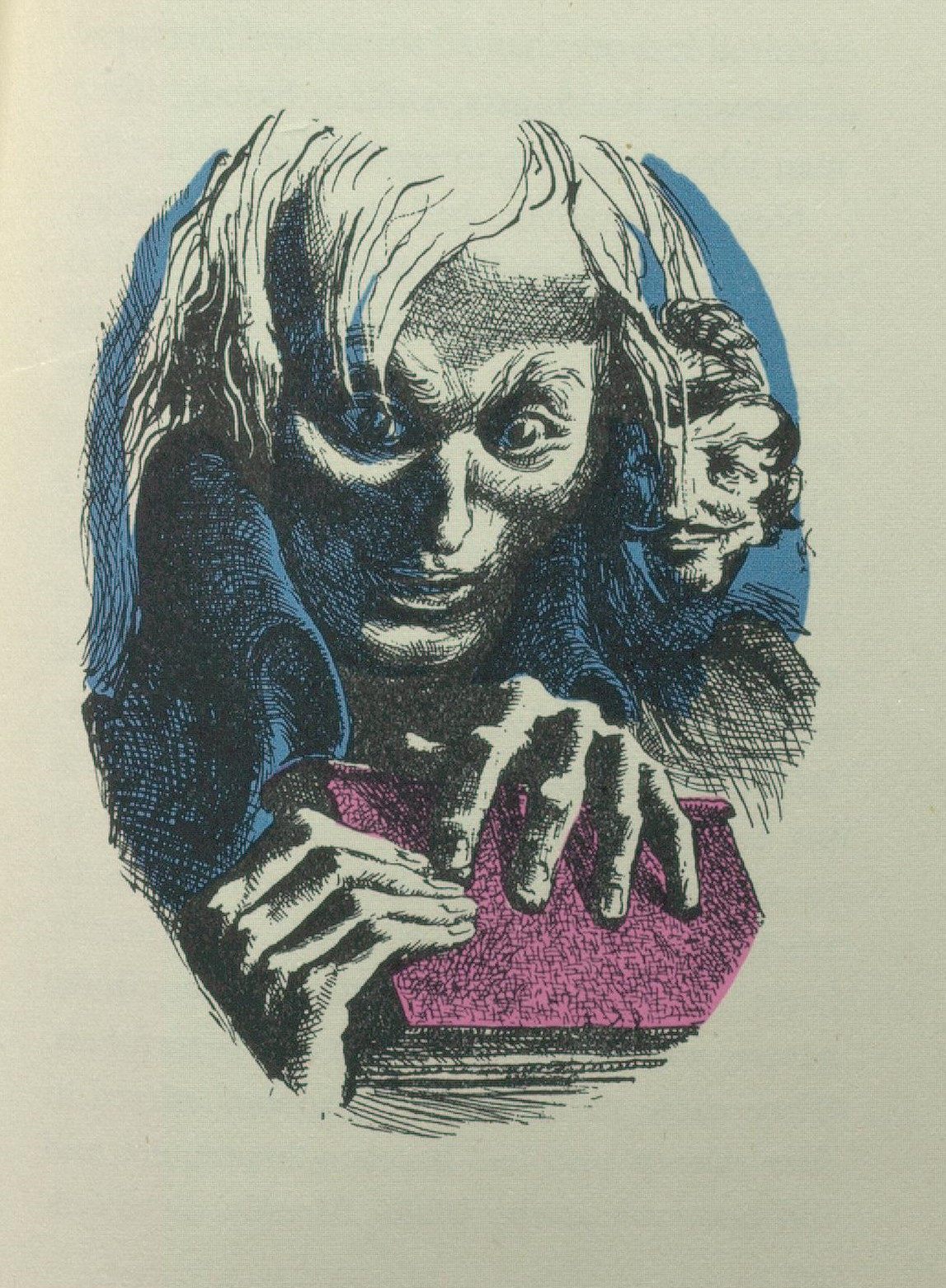

Bibliomania; or Book Madness contains many characters, but primarily follows Lisardo, a wealthy, fatherless young man who frankly confesses to being “an arrant bibliomaniac.” When he is introduced to a particularly glorious library filled with rare, antique books, he succumbs to mania:

“Lisardo ran immediately to the book-case. He first eyed, with a greedy velocity, the backs of the folios and quartos; then the octavos; and, mounting an ingeniously-contrived mahogany rostrum, which moved with the utmost facility, he did not fail to pay due attention to the duodecimos; some of which were carefully preserved in Russia or morocco backs, with water-tabby silk linings, and other appropriate embellishments.”

Although fictional, the characters in Dibdin’s book have uncanny resemblances to real-life bibliomaniacs of the time. “When this book was published in 1809, you know that the reader was someone from the upper class, and they knew people like that,” says Fernández.

For instance, English book collector Richard Heber had eight houses bursting with over 146,000 rare books, a collection he spent a fortune on—around 100,000 pounds—beginning in 1804. Meanwhile, the book collecting of Sir Thomas Phillipps eventually landed his family in debt. Phillipps was obsessed with vellum manuscripts, and stated that he was on the hot pursuit of obtaining one copy of every book.

One of his contemporaries noted that Phillipps’ house had become a dilapidated swamp of books: “The state of things is really inconceivable. Lady P. is absent, and were I in her place, I would never return to so wretched abode,” the man reported. “Every room is filled with heaps of papers, [manuscripts], books, charters, packages, and other things, lying in heaps under your feet, piled upon tables, beds, chairs, ladders.”

Today, behavior like this seems more like hoarding. Indeed, some contemporary scholars have linked bibliomania with obsessive compulsive disorder. “It is clear that what can be seen here is not ‘normal’ collection behavior but something more serious,” wrote Anna Knuttson in the Journal of Art Crime. “The pleasure that hoarders take in collecting can be so profound that it might define a person’s self-image and even give the individual a life purpose.”

Dibdin believed that the cure to bibliomania would come with the commercialization of books. His prediction came true. Over time, the desire to accumulate, catalog, and preserve became less intense with the advent of more efficient steam engine-powered printing press technologies in the 1820s. But Dibdin’s commentary remains a cautionary tale, relevant for today’s obsessives.

Ironically, Bibliomania; or Book Madness was widely popular among Dibdin’s fellow book lovers, with collectors getting in reckless bidding wars at auctions over a copy. The book is said to have spurred a 42-day auction at the 1817 Roxburghe sale.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook