The Old Man Who Claimed to Be Billy the Kid

Hico, Texas, has embraced ‘Brushy Bill’ Roberts and his tall tales.

History tells us that the outlaw known as Billy the Kid (aka Henry McCarty, aka William Bonney) was gunned down—at the ripe old age of 21—by Sheriff Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881, in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. He was buried, it is said, in Fort Sumner Cemetery, with his “associates” Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre, and the epitaph “Pals”—though none of them are likely directly under the tombstone there today. He’s since been romanticized in print, and on stage, television, and film as an emblem of the lawless West.

“As a society back then, people were tough, strong, and fearless, and yet this little guy is known as the most deadly outlaw of them all,” says Daniel A. Edwards, author of Billy the Kid: An Autobiography. “He is either a folk hero that single-handedly stood up against a corrupt government system, or he is a ruthless outlaw and cop killer that left a wake of terror in his path.”

Whether his story actually ended in 1881, however, is another matter. People in Hico, Texas—population 1,780 and home to the Billy the Kid Museum—tell a slightly different version.

In 1948, a paralegal named William V. Morrison was investigating a man named Joe Hines, a survivor of the Lincoln County War, the feud that helped make Billy the Kid’s name. Hines told him a whopper of a tale: Billy the Kid had not been killed in New Mexico but was alive and well and living in a town called Hico in Hamilton County, Texas, as one Ollie “Brushy Bill” Roberts. Morrison approached Roberts who, perhaps sensing the end of his life was near (if he had been Billy, he’d have been 90 at the time), made a confession. He hoped that Morrison could help him claim the pardon that New Mexico Governor Lew Wallace supposedly promised Billy the Kid back in 1879.

“Brushy Bill was very well known around these parts,” says Jane Klein, historian at the Billy the Kid Museum. “He would tell people around here, ‘You know, I have a secret and one of these days you’re going to find out what it is.’ He didn’t want to tell his story at first. After he thought about it, though, he told [Morrison] that he was Billy the Kid. All he wanted to do was to get that pardon that he’d been promised, and I believe he felt this was his last chance to get it.”

In November 1950, Morrison filed a petition on behalf of Brushy Bill. But it wasn’t to be. Roberts died a month later, and neither Billy the Kid nor Brushy Bill Roberts ever received a pardon. Since that time, debates have raged over Roberts’s claims, and whether he was truly one of the West’s most notorious gunmen or just an old man looking for attention.

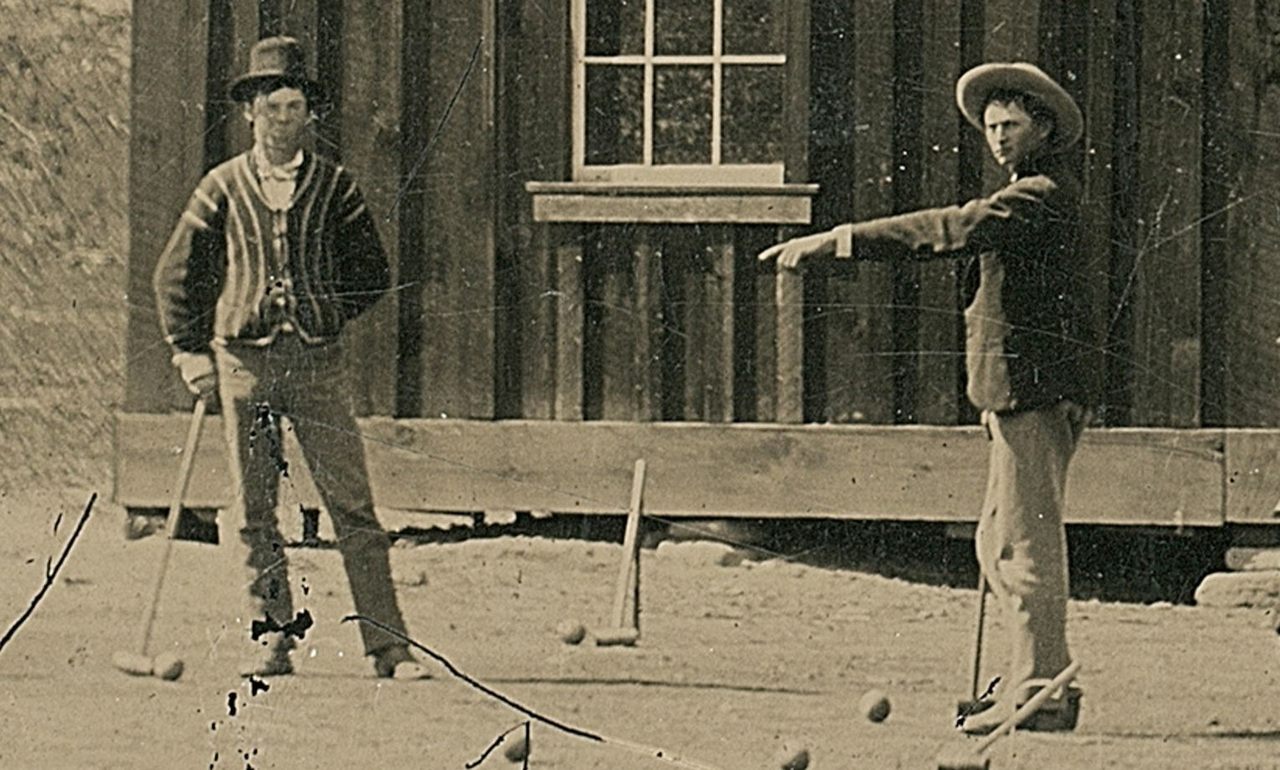

In researching his book, Edwards analyzed photographs of Billy the Kid and Roberts, and dug into the details of Roberts’s account of his life and compared them with known facts about Billy the Kid. “Before I made the discoveries I made in my book, I did not have an opinion on Brushy Bill,” says Edwards. “I now believe without a doubt that Billy the Kid was not killed by Pat Garrett in Fort Sumner. I believe he lived, had many more adventures … before he finally died in Hico in 1950.

“When you listen to his real story, he talks about how he wasn’t an outlaw, how he never robbed banks or stagecoaches, how he resented the fact that Governor Lew Wallace reneged on his promise of a pardon in 1879 and left him to die,” Edwards says. “Now these are strange things for someone that is a fraud to focus on. They are personal things, and things that make complete sense for him to be upset about if his story was true.”

The Billy the Kid Museum opened in Hico nearly 40 years after Roberts’s death, and the city actively celebrates the connection. In Hico Billy is everywhere, from a statue downtown, to the standee in the Chamber of Commerce, to the monumental arch over Roberts’s grave. There is no doubt there that Billy the Kid is one of their own, and they’re happy to tell the world.

“From what I’ve heard, [Brushy Bill] told a pretty credible tale,” says Hamilton Historical Commission Chairman Jim Eidson. “I believe all communities are built on legends, and in Hamilton County Brushy Bill’s stories connect us to those wild days of the frontier.”

Eidson’s “official” position on the story echoes that of the rest of the Historical Commission—we keep an open mind. We’re not trying to deceive anyone. It’s all just part of the area’s mythology.

“Brushy Bill and Billy the Kid, the whole story, that’s part of who we are now,” Eidson says. “I think people really like being associated with it now. Outlaws have a romantic air about them and I think the people in Hamilton County really enjoy having this as part of the history.”

This story originally ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook