The Black Composers of New Orleans Opera Are Finally Getting Their Due

And it’s all thanks to this mother-daughter dream team.

In the gloaming, two women begin to dance. They lift their hands to the sky, snapping to the piano’s rhythm, swirling their full skirts in time. The first, a red scarf wrapped around her waist, begins to sing, her words rising and falling like autumn leaves.

Around them, the scene, a simple patio set in the remains of the day’s tropical heat, takes shape as men in khaki uniforms raise their own voices in shades of tenor, baritone, and bass. It is the first time this opera, Lucien-Léon Lambert’s La Flamenca, has been performed in over a hundred years, just one of the dozens of forgotten works written by New Orleans’s 19th-century composers of color that local opera company OperaCreole is bringing to the stage.

Although classical music has always included the contributions of people of color, they have rarely had the recognition or opportunities afforded to white musicians, composers, singers, and stage producers. This was especially true in 19th-century New Orleans, where opera was as much of an essential cultural touchstone for the city’s free and enslaved Creole communities of color as it was for white residents.

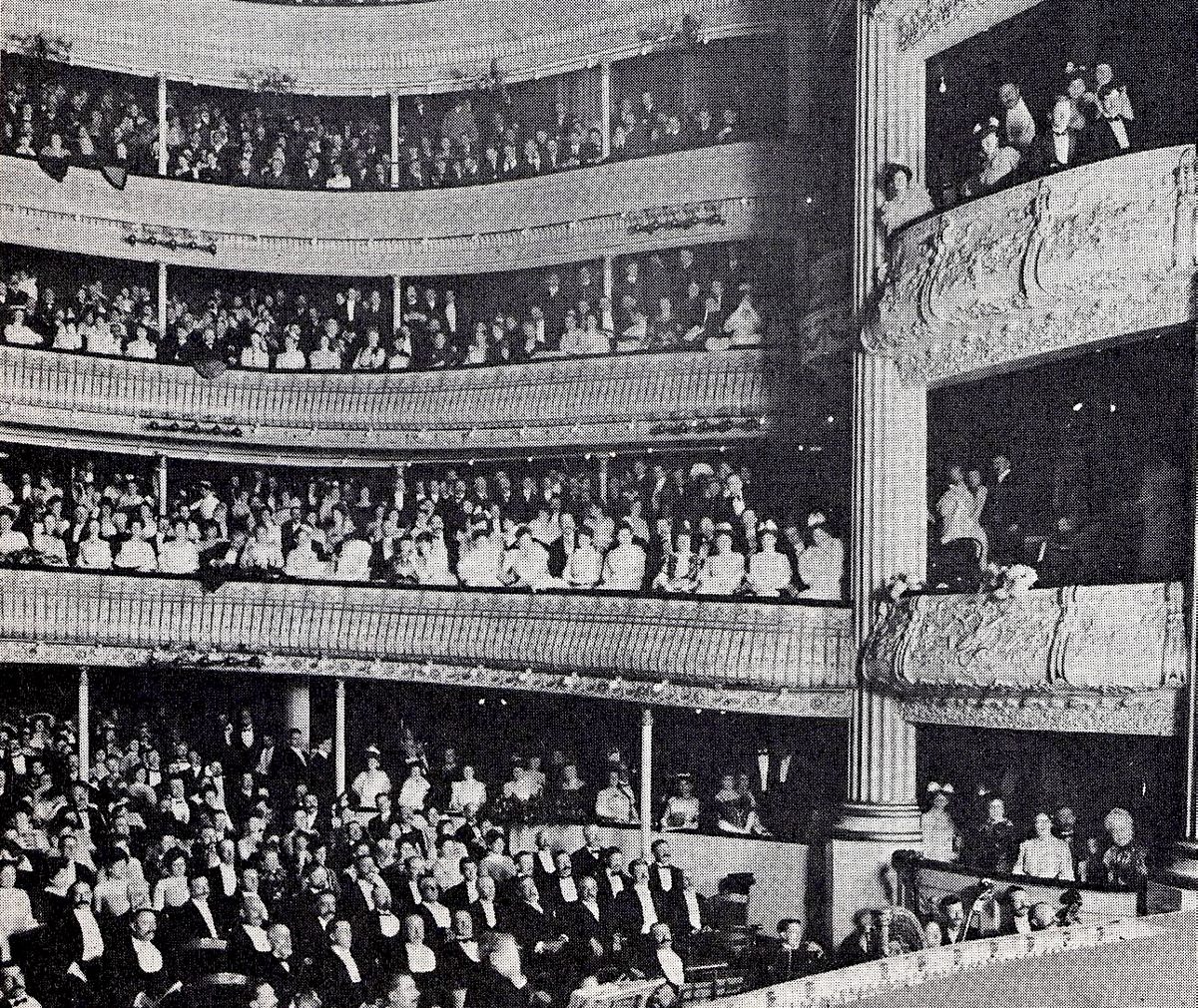

“It was like the pop music of the day,” says Givonna Joseph, co-founder and artistic director of OperaCreole. Not only did people of color attend the city’s multiple opera houses, there was also a brisk trade in sheet music for amateur musicians to play in the privacy of their own homes. Enslaved individuals were also permitted to watch the performances. “They were as educated in opera as the white audience,” says Jack Belsom, archivist for the New Orleans Opera Association.

Because many free Creole families had some wealth, New Orleaneans of color didn’t just go to the opera—their children studied piano, violin, and other musical instruments just like the children of well-to-do white families. “There were so many classically trained [Black] musicians that they formed their own orchestra in 1840,” says Joseph (at the time, New Orleans was divvied up into three separate cities). Creole musicians of color played in the premieres of more than 200 musical performances in New Orleans in the 19th century, she explains.

But with the opera stages dominated by touring groups performing the latest European works, New Orleans’s Creole composers had few opportunities to present their compositions. Much of their music has remained imprisoned on the page for over a century.

These works, and those of other lost composers of color, were exactly the ones that Joseph and her daughter Aria Mason, both New Orleans-grown, Black mezzo-sopranos, set out to perform when they founded OperaCreole in 2011.

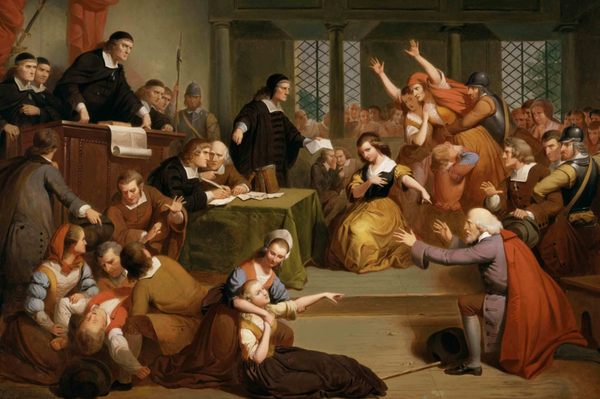

They envisioned a company that wouldn’t just be “promulgating great music and productions, [but] giving life to works that have been lost in some cases and deliberately suppressed in others,” says Mason, who also serves as the company’s production director. They would be performing “an act of restorative justice” by recognizing and creating a space for these works by composers of color.

The mother-daughter duo began to research Black Creole composers who’d left a paper trail—composers like Edmond Dédé, Lucien-Léon Lambert, and Eugene Victor McCarty. Some of the works they uncovered are pieces no one alive today knew existed, like the composition by African-English composer Samuel Colridge-Taylor found hidden in a drawer in Corden, England. Joseph is only half joking when she says that sometimes it feels like the composers are “bugging her from beyond.”

Joseph found Lambert’s La Flamenca at the Paris Conservatory of Music where he and other Creole musicians studied in the mid-19th century. “It was an easy piano score but all in French, and there was no real information” on the piece, says Joseph.

When a colleague translated the lyrics, she was surprised to find it was an opera revolving around the “immunes,” southern Black soldiers who were shipped to Cuba in 1898 to fight in the Spanish-American War because they’d developed immunity to yellow fever and other tropical diseases.

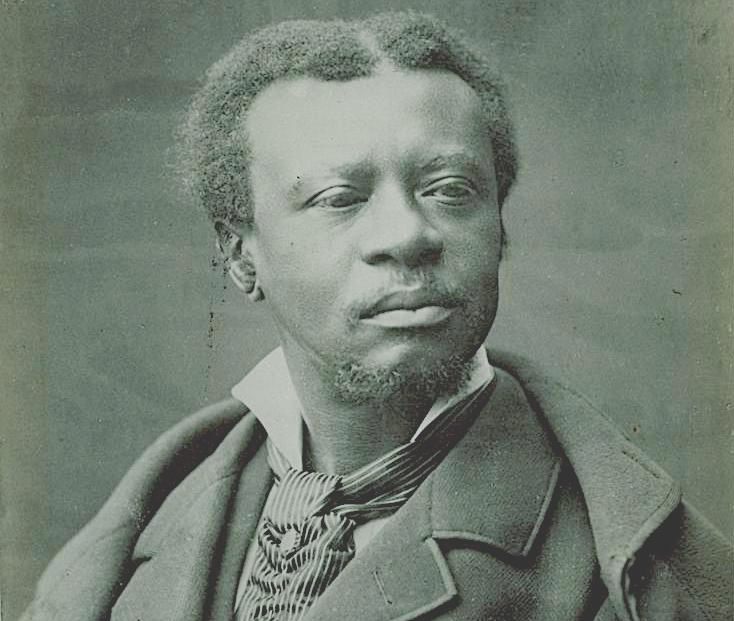

Lambert, along with his father Charles Lucien Lambert and his uncle Sidney Lambert, were among the most successful composers of color to emerge from New Orleans in the 19th century. But it was their contemporary, Edmond Dédé—likely the first Black American to study at the prestigious Paris Conservatory of Music in 1857 and to compose a full opera—who is arguably best remembered today, not because he came from New Orleans, but because he left it.

“Dédé moved to Bordeaux because he could not get the work here,” says Mason. “He was having a hard time getting his music published.” Even later, after 25 years as the director of Bordeaux’s L’Alcazar Theater Orchestra and the completion of his 1887 magnum opus Morgiane ou Le Sultan d’Ispahan, New Orleans’s theaters refused to stage his work.

When he returned to the city in 1893, “he was forced to perform in the private homes of well-to-do families and churches,” Mason continues. “He was not given the welcome he deserved.”

It’s a wrong that OperaCreole will finally make right in 2025. In collaboration with the National Opera House, Opera Lafayette of Washington, D.C., and the Consulate General of France in New Orleans, the company will stage the entire 550-page production. People of color will fill as many roles as possible, from singing on stage to working behind the scenes. “It will be completely history-busting,” says Joseph.

“To me, this is what civil rights is about,” Mason says. The history of New Orleans’s composers of color “should be as well known as Rosa Parks. Black culture has so many more expressions than we know.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook