Breathing While Saxophone Playing Should Be An Olympic Sport

Colin Stetson. (Photo: jean-daniel pauget/flickr)

Colin Stetson. (Photo: jean-daniel pauget/flickr)

When Colin Stetson, the Montreal-based saxophonist, performs, he looks as though he’s giving birth. Clutching his instrument, usually a gigantic bass saxophone that’s about the height of an average ten-year-old boy, his face turns bright red and then purplish, his cheeks distending and collapsing at irregular intervals. His forehead wrinkles with effort and shines with sweat. He’s built like a rugby player, and yet it looks as if playing the saxophone is taxing every muscle in his body.

Stetson’s music, jagged and rhythmic, is thoroughly unlike the smooth jazz popularized by saxophone players like Kenny G, but both Stetson and Kenny G rely on a technique to force their instruments to do things that saxophones really aren’t supposed to do. It’s called circular breathing.

Breath-powered instruments, which include everything from the trumpet to the didgeridoo to the saxophone, have one central weakness not shared by any other category: their operator must, at some point, stop to take a breath.

And in the same way that your car can’t be driven while you’re filling it up with gasoline, breath instruments are generally forced to endure a gap in play while the musician breathes. Scores for brass and woodwind instruments, like the trumpet and saxophone, were typically written with these pauses in mind; windows in which no music is played, called rests, were inserted into compositions to allow the musicians to take in air.

In other parts of the world, though, breath-powered instruments don’t allow this limitation to stop them. The didgeridoo of Australia, the zurna of the Balkans, and the suona of northern China are all breath instruments that are typically played without breaks, sustaining notes for minutes, sometimes hours, certainly much longer than any human can actually expel breath.

This is because the musicians who have mastered circular breathing are able to play without moving their lips from the instrument at all.

A didgeridoo being played. (Photo: Steve Evans/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

A didgeridoo being played. (Photo: Steve Evans/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

In essence, circular breathing turns your body into a set of bagpipes. “What you’re doing is inhaling through your nose, and at the exact moment you’re inhaling through your nose you’re pushing a small quantity of air using the muscles of your throat and the muscles of your face,” says Josh Sinton, a professional saxophonist and clarinetist who’s been using circular breathing for decades.

You use your cheeks as a sort of bladder for air, so when you need to inhale, you can use your muscles to push the reserves of air in your cheeks out through your mouth, keeping breath moving into your instrument. It’s not really “circular,” as you’re not recycling air, but it is a way to make sure that there’s never a time when you need to break.

It’s a tricky skill to learn, a bit like juggling: a mix of coordination, concentration, and muscle skill that, if done often enough, becomes second nature and doesn’t require active thought. It took Sinton a few years to learn how to do it flawlessly, but for the saxophone, it’s an advanced technique, not an essential one. For something like the didgeridoo, an ancient instrument from Australia, it’s indispensable.

“It took me about four months,” says Michael Hagmeier, an American didgeridoo player who once performed a song using circular breathing that lasted an uninterrupted two hours and 48 minutes, of learning the method. “The one trick was to fill a glass half full of water and put a straw in and try to keep the bubbles going,” he says.

The straw-in-water trick is also how Sinton learned. “One summer I was waiting tables and it was kind of a slow summer at the restaurant, so during my breaks I would just go over to my waiter’s station and sit there blowing bubbles into a glass of water. By the end of the summer i was able to do it really well,” he says.

Circular breathing is, first and foremost, a solution: musicians didn’t write songs around the technique, but created the technique in order to be able to play the kinds of songs and use the kinds of sounds they wanted. And the musical cultures where it’s most common tend to be cultures that heavily rely on droning sounds, steady noises that don’t change much and don’t break throughout a song. “We tend to do that a lot less in Western music,” says Hagmeier. “We have chord changes rather than drones.”

An exercise for learning circular breathing on a sax. (Photo: Storeye/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

An exercise for learning circular breathing on a sax. (Photo: Storeye/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

So there’s no single moment when circular breathing was invented, and no single genius who came up with the idea of using the cheeks as an air bladder to allow them to quickly sneak a breath. It was created independently, in various times and places, around the globe, from Sardinia to South Africa, Armenia to Australia.

It’s even tricky to try to pick out when it began to be used in western music. Sinton suggests that this is because the technique would have been stumbled upon by players who didn’t know the method had a name, didn’t know its history in other parts of the world, and didn’t necessarily even think they were doing anything special.

Portrait of Harry Carney in 1930 by William P. Gottlieb. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Portrait of Harry Carney in 1930 by William P. Gottlieb. (Photo: Library of Congress)

One of the earliest proponents of circular breathing, and perhaps the first to bring it to the mainstream, was Harry Carney, a saxophonist and clarinetist who played with Duke Ellington in the late 1920s and 1930s. Carney’s ability to hold notes for extended periods of time wowed audiences and musicians, who had never seen a sax player hold a notes for a minute or more. Here’s Hamiet Bluiett, a baritone sax player, describing Carney:

Three-quarters into the night, it was pretty much over, he stood up and played one note and everything in the place stopped. The cash register didn’t ring, didn’t nobody move, nothing happened. He played one note that lasted quite a long period of time. He hit the low note and the band came in and everything went back to as usual. I said that this horn has got something else to it. Duke Ellington had to be something else because one of the most magical things that I’ve seen happen, happened in his band.

Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, jazz musicians began experimenting vigorously with circular breathing, as well as basically anything else that was weird and could be loosely grouped under the category of jazz. Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who is perhaps best known for either stuffing three saxophones into his mouth and playing them all at once or for having played the lead flute solo on Austin Powers’ favorite song, used the technique liberally.

Members of the loose new tribe of avant-garde jazz musicians also used the form. Evan Parker, a British saxophonist, used the technique to play continuous streams of staccato, often dissonant, usually improvised notes, like a demented Bach suite. Anthony Braxton, an American, crafted some mildly transgressive jazz and then some totally bonkers stuff that sounds like he’s trying to strangle his saxophone. Roscoe Mitchell, another American, experimented liberally with both non-musical noise and with silence; circular breathing was simply another weapon in his arsenal.

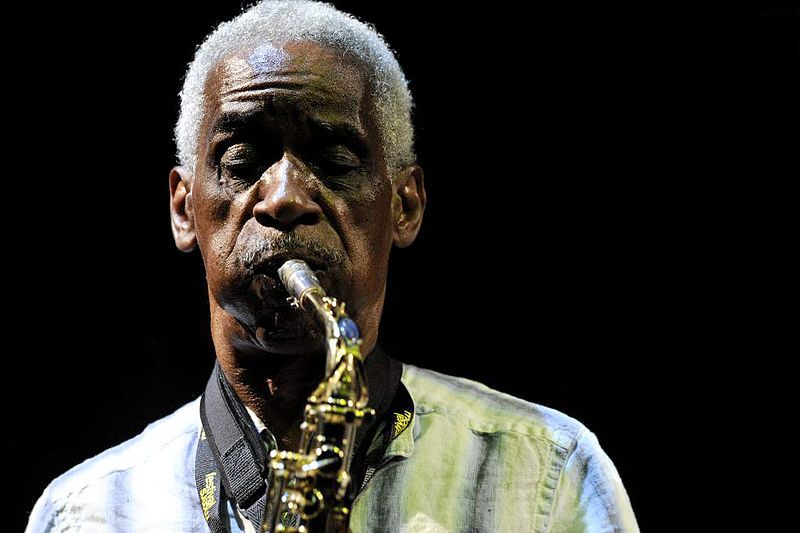

Roscoe Mitchell. (Photo: Nomo/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Roscoe Mitchell. (Photo: Nomo/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

For modern musicians like Sinton, Stetson, Kenny G, and Trombone Shorty, circular breathing is a tool that becomes more useful with experience. “I often just tell people it’s my monkey trick,” says Sinton. It’s an advanced method, but one that’s becoming increasingly important. “There’s a lot of classical music being written for bass clarinet over the past 30, 40 years, and it’s definitely considered a standard technique that any young serious bass clarinetist has to learn,” says Sinton.

It’ll sometimes even be noted on sheet music that you should begin circular breathing at a certain point in order to properly play the song, though more often it’s assumed that the musician can begin circular breathing fluidly as it’s required.

Circular breathing can, technically, be used with any breath-powered instrument. The basic technique of storing air in the cheeks and using chest and facial muscles to force it out while inhaling doesn’t change. But the difficulty varies widely based on the instrument. The key term to understand here is “back pressure,” referring to the amount of force needed to push air from the body into the mouth of the instrument.

Evan Parker. (Photo: Schorle/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Evan Parker. (Photo: Schorle/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

An instrument with a high amount of back pressure would require a lot of force—double-reed instruments like the oboe and bassoon would qualify. An instrument with low back pressure, like the flute, would require very little force. Brass instruments like the trumpet and trombone have a pretty high amount of back pressure needed. A didgeridoo is somewhere in the middle; you restrict the size of the opening with your lips.

Surprisingly, it’s actually easier to perform circular breathing on an instrument with very high back pressure. “If you encounter resistance when you breathe out, it actually makes it a little easier to do a circular breath,” says Sinton. “It gives you a little more time to inhale and kind of restart the process.”

The technique is both challenging to master, and, depending on the instrument, physically demanding to perform. It can be exhausting to play instruments like the bass saxophone and the trumpet; the human body isn’t really designed to expel copious amounts of air and vibrate the lips for hours on end.

“You have to become aware and in control of all these muscles that surround your thoracic cavity,” says Sinton. “It’s like a very nerdy form of athletic training.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook