This New York City Map Is Full of Dutch Secrets

When Broadway was a broad way and Wall Street was a wall.

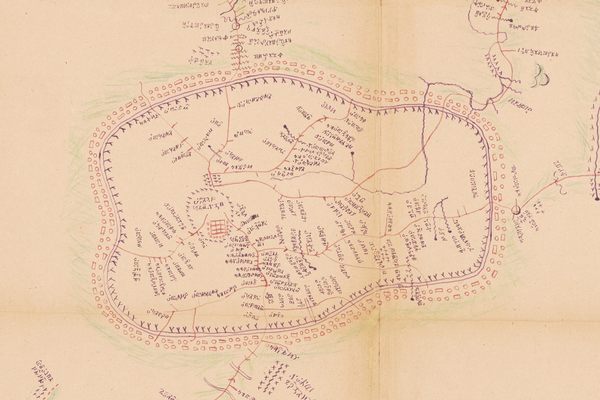

Four hundred years ago, the Dutch established the colony of New Amsterdam on the southern tip of the island of Mannahatta. A map of the settlement circa 1660, known as the Castello Plan, offers a birds-eye view of a thriving community of about 1,500 people. There are houses, businesses, extensive gardens, windmills, piers, and boats bobbing along the rocky coast. Near the southern end of the island stands Fort Amsterdam flying the flag of the Dutch West India Company. On the western side, a broad way stretches north from the fort toward a wall that crosses the island from east to west.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked these streets,” says author and historian Russell Shorto—and he’s not speaking metaphorically. Follow the map today, and you can find yourself standing in New York City’s Financial District at the place where that broad way—today’s Broadway—and the northern wall—Wall Street—meet. Simply put, the Castello Plan is a map of Manhattan before it was Manhattan. “We’re entering New Amsterdam,” says Shorto.

The details shown on the map have been erased by time, as New Amsterdam became New York City and landfill projects reshaped Manhattan’s shoreline, but the streets, though renamed, remain, among them Broadway; Wall Street; Pearl Street, which then marked the island’s eastern border; and Broad Street, once home to a canal that ran through the center of the settlement almost to the modern-day Exchange Place. The footprint of Fort Amsterdam remains too; today the 20th-century Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House occupies the site.

Close your eyes and you can imagine these blocks as they looked in the mid-17th century. “I always think of it as kind of a little Wild West-looking town, but with Dutch gable houses,” says Shorto, who wrote The Island at the Centre of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. He points out a house on the map that once stood near the modern-day intersection of Pearl and Whitehall streets. Lenape people came there to trade corn and venison with the settlers. On what is now South William Street, Shorto identifies a modest building where dozens of African people enslaved by the Dutch West India Company lived. “This map has been imprinted in my mind for a long time,” he says.

But until just before the opening of a new exhibit at the New York Historical Society featuring the Castello Plan (on display March 15 through July 14, 2024), Shorto had never seen the artifact in person. The most revealing map of the origins of New York City is in the collection of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Italy. It has rarely been displayed on the island it depicts.

![Johannes Vingboons painted this watercolor of New Amsterdam at the moment it became New York, captioning his work, “New Amsterdam or now New York on the Island Man[hattan].”](https://img.atlasobscura.com/HHcF3dRUxEwg0YL07tMyBkLTq-U_12PUsJ13KG02hnQ/rt:fill/w:1200/el:1/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy8wNjI2YjcxYTQw/ZTg1ZmRmMjNfMSBW/aWV3IG9mIE5ldyBB/bXN0ZXJkYW0sIFRo/ZSBjYXN0ZWxsbyBw/bGFuIGJyb29rbHlu/IG1lbnUsIHRoZSBj/YXN0ZWxsbyBwbGFu/IG1hcCBwaG90b3Ms/IG9sZCBtYXAgb2Yg/bWFuaGF0dGFuIGlz/bGFuZCwgbnljIGhp/c3RvcnkgbXVzZXVt/LCBuZXcgeW9yayBo/aXN0b3J5IG11c2V1/bSBueWMgLmpwZw.jpg)

The story of the Castello Plan begins in about 1660 at the height of the settlement, when Jacques Cortelyou, a prominent resident of New Netherlands and surveyor-general of the province, created a map of New Amsterdam. (Perhaps in the small building facing Fort Amsterdam he rented as office space, near the corner of what is today Whitehall and Bridge streets.) The map—and an accompanying census offering such details as who rented which building—was then sent to old Amsterdam, where Johannes Vingboons, a noted cartographer and watercolorist, created a replica of the work.

The original has since been lost, but the replica was later bound into an atlas that was sold to Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, while he was visiting Holland in the late 1660s to tour some well-known Dutch painters’ studios. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that the geographical world rediscovered the map: this centuries-old map of a long-gone Dutch New World colony was hanging on a wall in the Villa di Castello, a country estate that once belonged to de’ Medici, outside of Florence.

“Throughout much of our history, we’ve looked at American beginnings through English eyes,” Shorto says. Like the Castello Plan itself, the story of Dutch New Amsterdam was long overlooked. But the Dutch colony is key to understanding New York today, Shorto says. The settlers imported their ideas of pluralism and business from Europe. “This multi-ethnic community and its capitalist ethic has defined New York from the very beginning,” he says.

When Shorto proposed creating an exhibit commemorating the 400th anniversary of the founding of New Amsterdam, he knew he wanted to bring the Castello Plan back to New York. It has become the centerpiece of a complicated, multi-layered story about the history of Manhattan.

Included among the artifacts on display is New York’s “birth certificate”—a letter describing the purchase of the island from Indigenous people, the terms of which are much debated—and a mpungu collection. This mpungu is a trove of bones and teeth, fragments of a pipe, a copper thimble, stoneware marbles, and other small items which were discovered in a basket buried under a Dutch plate near a home that once stood on present-day Pearl Street. It is evidence of an enslaved person, who brought parts of their culture to the island, too, says Shorto. In some central African cultures these mpungu—“to stick together”—have healing properties.

That’s the story Shorto sees when he looks at the Castello Plan. (An interactive version created in partnership with the New Amsterdam History Center makes that view accessible to all.)

“New Yorkers are coming to appreciate that their beginnings are quite different from other parts of colonial America,” Shorto says, “and that directly connects with what New York has become.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook