A Look Inside the Last Colorful Oxcart Factory in Costa Rica

Uriel Alfaro Castro shows his handmade Aztec wheels, which outperformed European designs.

When Uriel Alfaro Castro was 13 years old, he followed his seven older siblings to start his first day of work at the family oxcart factory. His father, Eloy Alfaro, who founded the factory in 1923 in Sarchí, Costa Rica, asked his son which craft he wanted to learn to help construct the carts. Out of woodworking, blacksmithing, and mechanics, the young Castro chose mechanics—and 70 years later, he is still diligently constructing oxcarts in the tiny town of Sarchí, masterfully crafting each part by hand with the help of his associates.

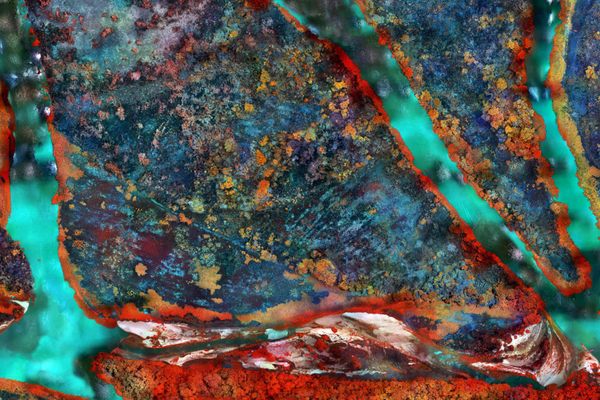

Oxcarts have been commonly used throughout Central America, but those sporting bright colors and intricate patterns are unique to Costa Rica. They were essential to Costa Rica’s growth, enabling the transport of coffee from the rugged mountains to the coasts for export. When the Spanish used European-style carts starting in the 1840s, their open spoke wheels regularly broke or became trapped in the mud. Costa Ricans improved the cart design using a solid construction based on Aztec wheels. In the early 20th century, painting the carts bright colors with intertwining patterns became commonplace, as did adding bells and whistles, so each cart played a signature song whenever it moved. Some artists still add a musical feature to this day.

Sarchí was once the hub of oxcart creation, but now, Castro’s Fabrica de Carretas Eloy Alfaro is the last factory in the country still manufacturing oxcarts for distribution.

The year 2023 marked a century of business, and Castro and a handful of talented craftspeople are still dedicated to keeping this proud Costa Rican tradition alive. But they are not sure who will keep their legacies going—Castro is the last of his family working in the factory, and his children followed other paths in life. Castro says very few young people are interested in making oxcarts in their entirety these days, but because of their cultural significance (painted oxcarts come out in force every March for Dia de los Boyeros, or Oxcart Drivers Day), he hopes some will take up the tradition before it disappears.

Here’s a close-up view of the last oxcart factory in Costa Rica.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook