The Once-Common Practice of Communal Sleeping

What’s a shared bed between colleagues, anyway?

In the beginning there was a pile of leaves and a cave floor. Sleep was punctured by an orchestra of nocturnal sounds: the murmuring, snoring, farting, rustling, and heavy-breathing of many bodies packed together in slumber. They emanated equal parts warmth and stench. But together they passed another night in safety. And it was good.

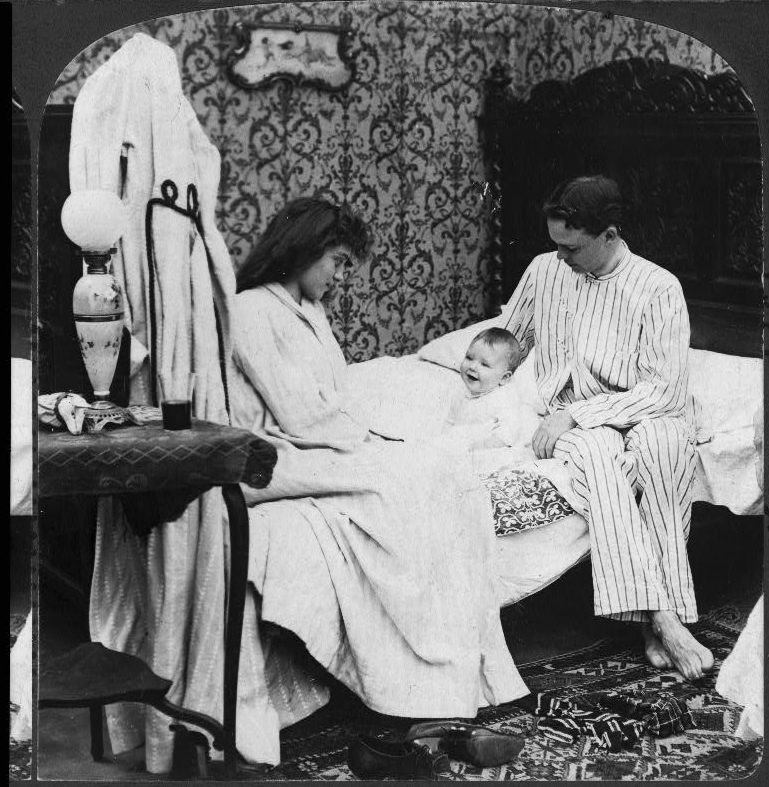

Sleep has been a communal activity for millennia. In the days before central heating and alarm systems, bedmates were a necessity. Entire families would pack together on a single mattress (plus guests), servants often slept alongside their mistresses, and strangers frequently shared a bed while traveling.

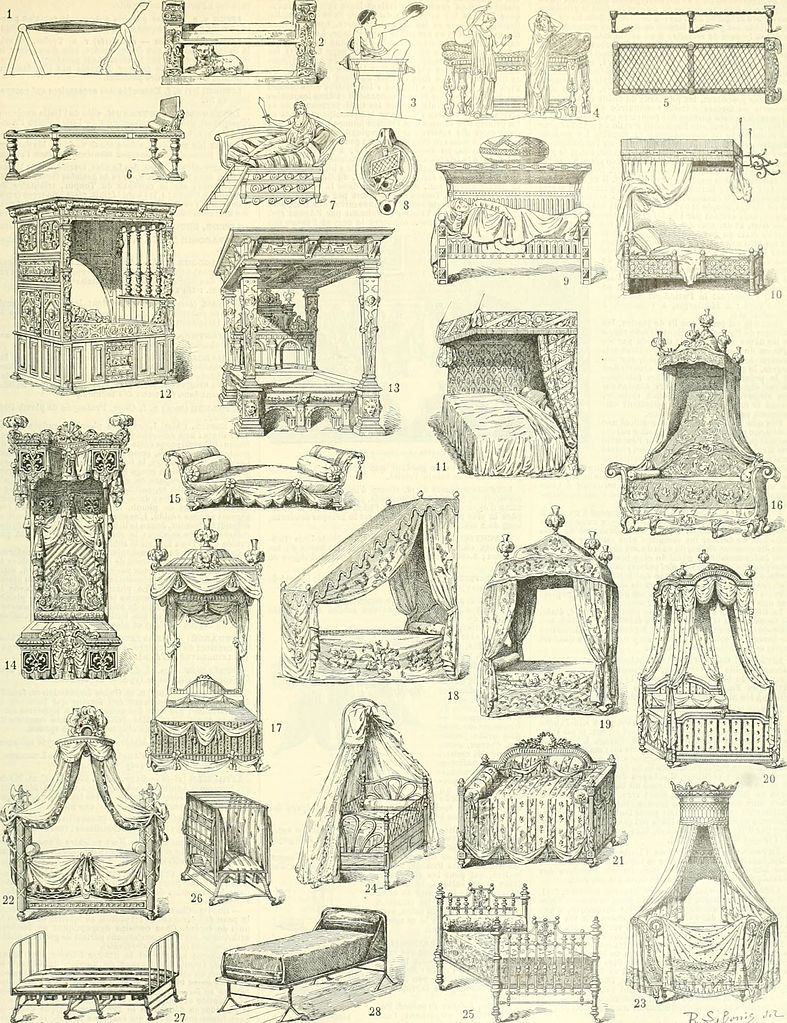

While people have always needed a place to sleep, beds themselves are a relatively new concept. Beds remained glorified piles of leaves for a shockingly long period of time. The wheel was invented, animals were domesticated, societies were founded, and still, for most people, a bed was some meager bit of cloth providing the most basic level of separation between them and the cold, hard ground. In the grand houses of medieval Europe, much of the household gathered in the great hall to pass the night on blankets or cloaks. If they were lucky, they literally hit the hay—which they stuffed into a sack and used as a mattress.

By the 15th century, beds in affluent homes were beginning to take on their modern form. They had wooden frames and other sleeping accoutrements, like pillows, sheets, blankets, and even a mattress. As historian Lucy Worsley points out in her book If Walls Could Talk, sleeping alone in a grand 16th-century English bed would have been a rather lonely experience. The wealthy had acquired a taste for beds, and they built them big, elevated, canopied, and curtained. In fact, the bed was often the most expensive item in the home—therefore few but the richest could afford more than one. This meant that entire families sometimes shared one bed, as well as the covers. People were not discomfited by this, especially not in poor households where the communal bed offered families a rare place to gather and bond.

Communal sleeping was not restricted to the nuclear family. Mistresses sometimes shared their beds with female servants to protect them from the unwanted advances of male members of the household. Many servants slept at the foot of their master’s beds (no matter what bedtime activity was happening in that bed).

But if anyone were to get any kind of rest while sleeping next to others, lines had to be drawn and rules applied. Large families assigned spots to each member according to age and gender. The British called this “to pig.” In his book, At Day’s Close, historian A. Roger Ekirch recounts how one 19th-century Irish family slept in birth order with the mother and sisters on one side of the bed and father and brothers on the other, followed by the odd guest or traveling peddler.

It was not uncommon for strangers and traveling companions to share a bed while on the road. Etiquette dictated that to ensure relative tranquility when sharing a bed with strangers, a bedmate was to lie still, not hog the blankets, and generally keep to one’s self. But that didn’t always work. In 1776, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams spent a night sharing a bed at a New Jersey inn which was largely passed bickering over whether to keep the window open or closed.

Clearly, privacy in pre-industrial America and Europe was in short supply. Most people did everything under the gaze of others. They slept, ate, and attended to personal matters, all in the presence of their family members, servants, and farm animals.

Private moments were snatched whenever and wherever they could be. And that often happened in bed. Away from the prying eyes of servants and neighbors, siblings whispered secrets in each other’s ears and husbands and wives engaged in candid conversation. The bed acted as a kind of neutral territory between couples. Ekirch writes that it was a place where women found rare moments of autonomy within the patriarchal household. “Sexual boundaries were redrawn. Lying abed in the dark encouraged wives to express concerns unsuited to other hours.”

Bed-sharing had other perks, too. It was an opportunity to transgress social norms. Male servants who shared a bed sometimes engaged in sexual relations, and it was not unusual for illegitimate babies to be conceived when male and female servants became bedmates. The hierarchical relationship between mistresses and their female servants softened and loosened when they shared a bed.

So who finally put an end to communal sleeping? The Victorians.

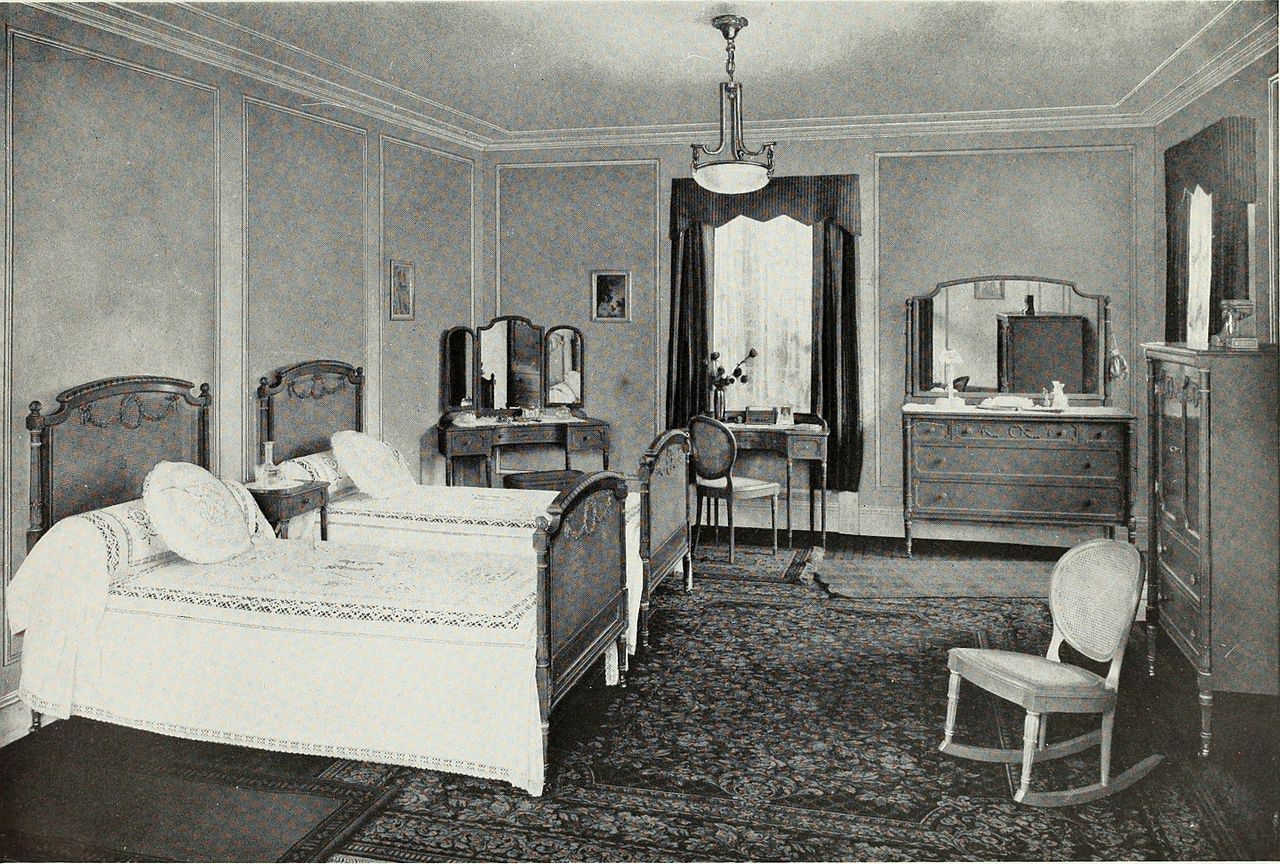

The Victorian home abounded with rooms and was bisected into the realms of servants and masters. This marked a shift toward privacy that had been slowly taking place over the past two centuries. Individual bedrooms were assigned to each family member, and gradually the idea that communal sleeping was improper and downright immoral took hold and trickled down to the lower classes.

These separate spheres extended to the marital realm. Couples now not only had their own rooms, but their own beds as well. This offered the appearance of propriety that Victorians coveted. However, there was an even greater reason that his-and-her beds came into vogue: disease.

During the mid 19th-century, there were many anxieties about public health. It was thought that diseases generated spontaneously where foul water and air lived, and a sleeping body was a prime offender.

In her housekeeping guide published in 1892, Mrs. Elizabeth F. Holt warned readers that “the air which surrounds the body under the bed clothing is exceedingly impure, being impregnated with the poisonous substances which have escaped through the pores of the skin.” There were other health concerns, too. One Dr. B. W. Richardson writing in 1880, advised that children not share a bed with an adult because the aged suck the “vital warmth” from children. Also, no one wants to deal with “heavy” and “disagreeable” morning breath.

Separate beds had other benefits as well. The late 19th-century saw the advent of the “new woman.” She no longer wanted to be subservient to her husband and she actively claimed a new level of autonomy within her marriage. This shift was displayed in the middle-class bedroom where sexual boundaries were redrawn once again. In the grand old debauched marriage bed, wives were always available to their husbands. Separate beds marked an equipoise between the couple. “Twin beds are visually equal to each other; they take up the same amount of space,” says Hilary Hinds who authored an article titled “Together and Apart: Twin Beds, Domestic Hygiene and Modern Marriage, 1890-1945.” “There’s a kind of pause between one bed and the other. There would have to be some kind of conscious negotiation, or at least some conscious decision to move from one to the other.”

Twin marital beds had a good run. After the Second World War, working wives returned to the home and there was a greater emphasis on family togetherness. “There began to be a turn against twin beds as somehow dividing the couple at the point where they needed to be at their closest and their most intimate,” says Hinds. Well into the 1960s, Sears and other large department stores in both America and England, advertised twin beds for middle class married couples. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that a consensus was reached: “Twin beds were old-fashioned and unhealthy and prudish,” Hinds says. “No self-respecting couple would willingly embrace twin beds from now on.”

Recent research out of Ryerson University in Toronto supports Dr. Richardson’s assertion that couples sleep better when they sleep apart. In Canada, it’s estimated that as many as 30 to 40 percent of couples are embracing the idea. But the stigma of the twin bed remains strong. “I don’t think there is going to be any revival in twin beds any time soon,” offers Hinds. So communal sleeping lives on, but only for couples. Everyone else is fated to sleep alone.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook