A Painting of a Crying Boy Was Blamed for a Series of Fires in the ’80s

The artwork, said UK tabloids at the time, was haunted.

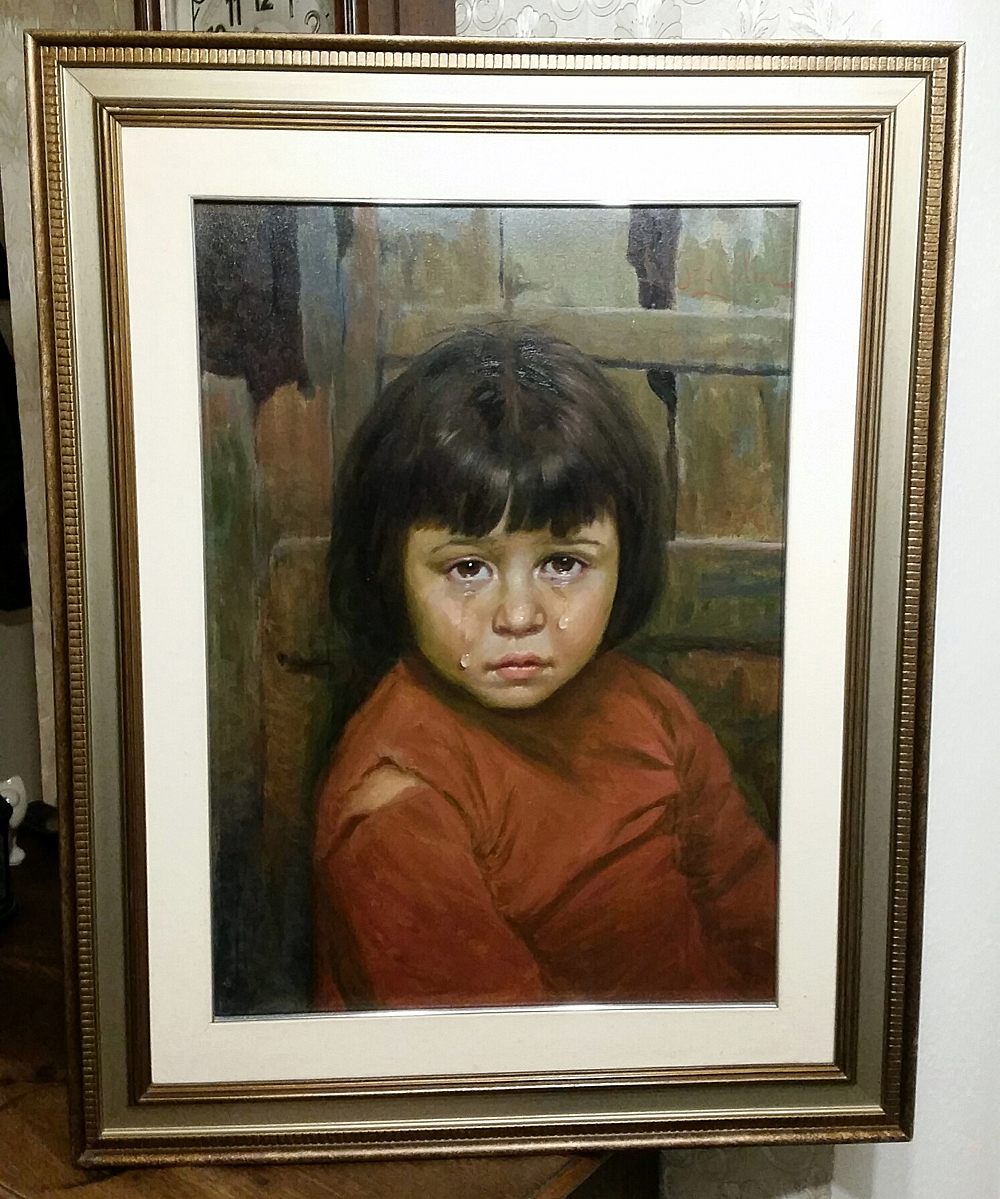

In the middle of the night in Thatcher-era England, a home in South Yorkshire succumbed to a fire. The lounge room was charred black, drapes and furniture reduced to ash. The owners of the home, Ron and May Hall, lost nearly everything to the blaze, except one item: a painting of a crying boy, his wide eyes looking out from the wreckage, not even blackened by smoke.

This wasn’t the first time a picture of a crying boy had been found amid the ashes of a torched home.

On September 4, 1985, British tabloid The Sun published “Blazing Curse of the Crying Boy Picture!” a story about a very unlucky painting that caused fires, supported the comments of a local fire station officer. These paintings, the firefighter said, turned up mysteriously unscathed in fires across the U.K., all of which started spontaneously. It was well-known; he would never think of owning this cursed painting himself. “The couple had laughed off warnings” that their painting was cursed, wrote The Sun. Let all other heed the warning, and get rid of their own giant paintings of crying children immediately.

If the fact that paintings of crying kids were hung in the living rooms of multiple households makes you double-take, you’re not alone. The paintings, an odd relic of mass-printed art, were readily available in stores during the 1950s-1970s, and tended to appeal to young couples. While the paintings have not been reprinted for decades, their bizarre subject matter and backstory have kept the legend going, from copy-pasted internet legends to books of local lore.

The legend of the crying-boy painting seems to have begun with The Sun, fueled by the obscurity of the crying-boy painting’s artist. The artworks bear the prominent signature of one Giovanni Bragolin, but for quite some time no one could find information about the man. Rumors abounded; he painted hundreds of crying children, many of them street urchins, it was said, in either Italy or Spain. Finally, a 2000 book of creepy stories called Haunted Liverpool claimed that, in 1995, a “well respected” school teacher called George Mallory discovered that the painter was actually a mysterious figure named Franchot Seville.

The following backstory, from 2000, seems to be a mash-up of reportage from The Sun and Mallory: one of the urchins he painted was a boy named Don Bonillo, who accidentally started a fire in which his parents died in Spain. From then on, wherever the boy went, a fire followed, prompting his nickname, Diablo. Some believe the boy was adopted against the will of a priest, and was abused by the painter; in the 1970s the boy was consumed by fire as well, in an explosion caused by a car accident.

According to journalist David Clark, who researched the crying boy legend for Fortean Times and on his website, this legend has more than a few holes. Giovanni Bragolin and Seville seem to have been one of a few pseudonyms for Spanish painter Bruno Amadio, and Clark could not find evidence that George Mallory nor Don Bonillo ever existed. Amadio likely painted 20-30 of these crying boys after training in Venice after WWII, prints of which were sold in department stores through the 1970s, wrote Clark. Another artist, Anna Zinkeisen, had a similar series of crying children paintings that were regarded as equally cursed.

In The Martians Have Landed, Robert Bartholomew and Benjamin Radford reported that many people wrote to other newspapers in response to The Sun’s coverage, including one woman who couldn’t “think of a reason such a lovely picture could suddenly be thought to be jinxed,” yet wanted to toss it for safety’s sake. Despite skeptics’ responses to the public’s distress via interviews and open letters, the story held. A post on the website of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry says that The Sun added salient details, such as that the urchin was mistreated by the painter, with the explanation that “these fires could be the child’s curse, his way of getting revenge.” According to Clark, The Sun was competing for readers with the Daily Mirror when the opportunity to develop the story arose, and the internet further grew the tale.

Comedian and writer Steven Punt also explored the legend on his radio show Punt PI. He attempted to track down the homes involved, and found Jane McCutchin, who had hung the print in her living room in the 1980s. McCutchin, a mother of two, was cleaning her kitchen when she found that her hand-made drapes, blinds and curtains were suddenly ablaze. Her family escaped alive, but her home had been destroyed—except for a single painting hung in her living room, of the crying boy. “You could still see the little boy’s face on the painting,” she told Punt. Later, she heard a firefighter who saw the painting say: “Oh no, not another.” After what was described as a “series of coincidences” and bad luck, McCutchin speculated that the painting was the cause, prompting her to get rid of it.

Most of the fires had normal causes, like cigarettes, or unwieldy deep-frying pans. Since most of the myth surrounds the nearly unbelievable fire resistance of the painting, Punt bought a crying-boy picture of his own; after being inexplicably delayed on his destination several times, Punt began to feel a bit nervous about the possible curse. When he tested its fire retardancy by setting it alight with construction researcher Martin Shipp, they found that beyond the string it hung from, it didn’t really burn. While the lapel of the boy’s jacket was singed, and the painting suffered a hole, the damage stopped pretty quickly. This may have been due to a fire-retardant varnish, he and Shipp surmised, which would easily account for why the painting would remain little-touched in burned homes across the U.K. During his own investigation, Clark also discovered that the painting was printed on compressed board, making it difficult to burn.

Such explanations would not have sufficed in 1985. In the middle of the story’s initial heyday, The Sun decided to take the legend further, requesting that the public send their crying boy paintings to them to be destroyed. According to The Sun’s editor, the office “got swamped in crying boy pictures,” but the editor refused to display the paintings in the office himself. “Picture is a fire jinx”, the paper reported. A week after its first article on the curse, The Sun published “Crying Boy Curse Strikes Again”—though the painting under the headline was a completely different painting of a crying boy. The story was much the same; an ordinary fire turned creepy when an unscathed crying-boy painting was found hanging in the house.

The legend of the crying boy survived into the internet age, and even sparked fan clubs. If you search for this online today, you’ll sadly find that the fan club since dissolved—but evidence of its existence in 2002 is preserved on artist and coder Mario Klingemann’s former blog, where there were discussions of crying-boy painting sales and a Holland-based club. Klingemann first got into the legend through the art of Laura Kikauka, who replaced the crying boy’s eyes with red LEDs, and for him, the painting’s weirdness is the allure. “The legend is a nice add-on … I think as a child when we did holidays in Italy back in the 1970s, I had also seen those pictures sold at some street booths and I guess I found them quite peculiar back then,” says Klingemann, who also created a crying-boy tear generator. Klingemann has collected several of the paintings, occasionally fielding requests to sell or buy from enthusiasts. Despite his fascination with the story, Klingemann maintains that he does not believe in the curse.

According to Gail-Nina Anderson in her paper about art folklore, the crying boy legend grew quickly because everyone could participate—the paintings were cheap and easy to find. The Crying Boy painting legend became so widespread that it grew to include all versions of similar paintings by various artists, including “cursed” paintings of crying girls.

The Sun capped most of its hype of the legend in a 1985 article on Halloween, with the headline “Crying Flame!” gracing the front page. The paper claimed to dissolve the curse once and for all with a bonfire, burning “sackfuls” of paintings, which were sent to them by the public in response to their call. The bonfire blazed near the River Thames, dissolving the curse into smoke. The Sun, ever-looking for reliable sources, quoted a chaperone to the event; a fire officer who said, with relief: “I think there will be many people who can breathe a little easier now.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook