Defy Age Using a 3,600-Year-Old Face Cream Recipe With a Deadly Ingredient

The ancient Egyptians were far ahead of their time.

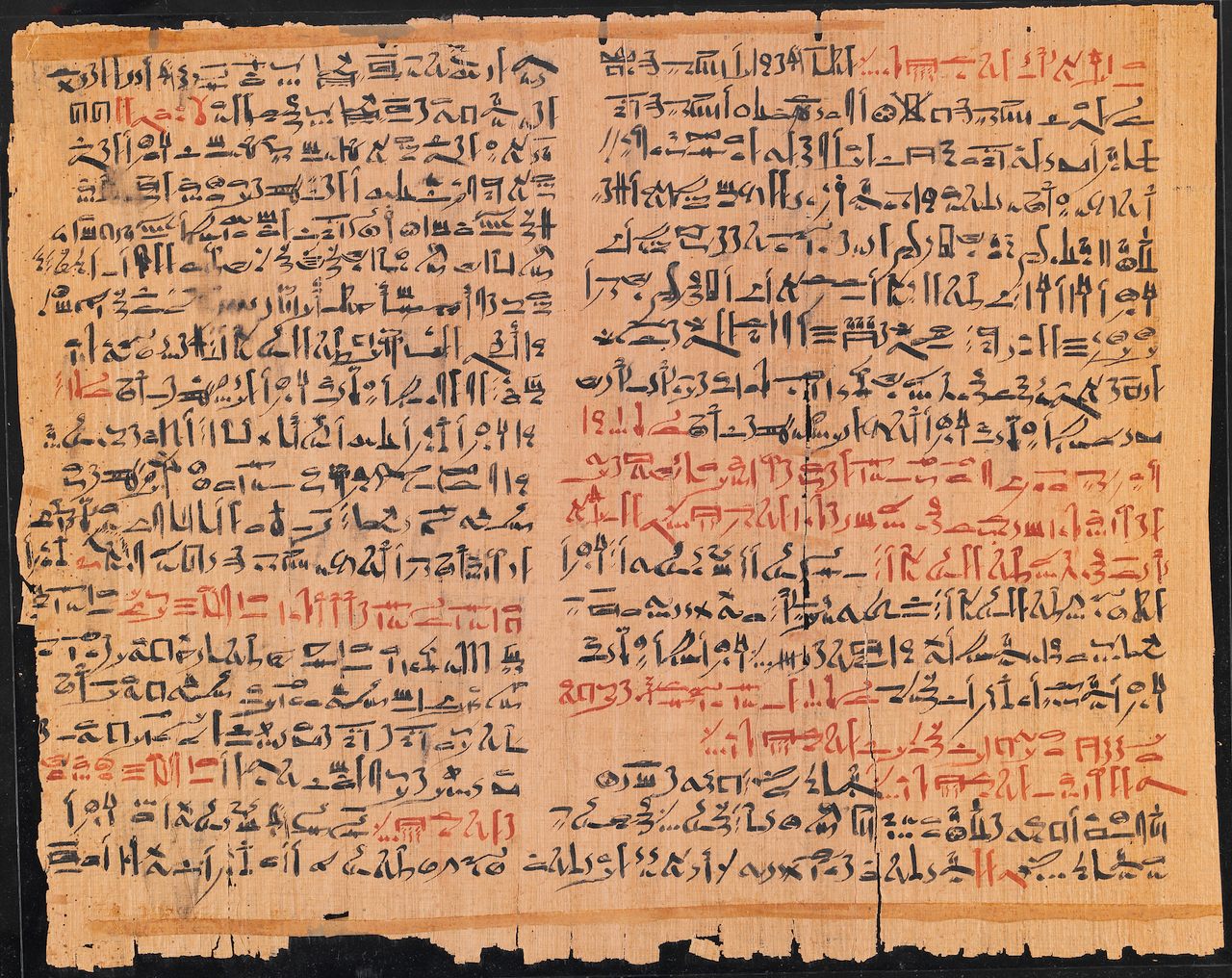

Stanley Jacobs has been fascinated with ancient Egypt for as long as he can recall, but his obsession with one particular passage in one particular document started a little over 15 years ago. At an annual meeting of Egyptology enthusiasts, he hunted down, on the recommendation of a patient, an ancient Egyptian text about surgery known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

This document is “one of the two most important medical texts from ancient Egypt,” according to Egyptologist James Allen, and the case studies it contains date back 5,000 years, to the time when Egypt’s great pyramids were built. It’s one of the oldest records of surgery in the entire world, and when Jacobs first read through, he was impressed.

A plastic surgeon himself, he found that most of the cases were about “really good reconstruction after traumatic injury, of the nose, the neck, the spinal cord,” and that its techniques were surprisingly well thought out for a millennia-old book. What really intrigued him, though, was a recipe at the back of the book, titled “Transforming an Old Man Into a Youth.”

This section of the papyrus is a long and complicated set of instructions for making what is, essentially, a face cream. The original translator of the papyrus, the Egyptologist James Breasted, hadn’t been much impressed by it, writing that the recipe “proves to be nothing more than a face paste believed to be efficacious in removing wrinkles.”

As a doctor who spends a lot of time thinking about skin, beauty, and age, though, Jacobs wasn’t so quick to discount it. “I realized that if they’re that serious about their surgical treatments, they’re probably serious about this,” he says.

Jacobs wanted to try this recipe out himself, but when he examined the recipe, he ran into a problem. The key ingredient was “hemayet-fruit,” and he had no inkling of what that might be.

Despite the recipe’s alluring title, it’s no shock that Breasted dismissed the recipe for “Transforming an Old Man Into a Youth.” When he was working on his translation of the papyrus, in the 1920s, he was dazzled by the wonderful discoveries to be made in the text—some of the earliest anatomical and pathological descriptions on record, the earliest written reference to the brain. The Edwin Smith papyrus (now held by the New York Academy of Medicine) had been in private hands for decades when he was asked to translate it, and no one had recognized its significance.

Edwin Smith had been not an average American, it’s safe to say. Born in the early 1800s, during the “Era of Good Feelings” when America was flush with its success as a young nation, Smith left his home in Connecticut to study in Europe and settle in Egypt. In those antebellum years few other Americans would have chosen to study hieroglyphics and live under Ottoman rule, but Smith made a life as an expatriate in Luxor, across the Nile from Egypt’s most famous monuments, where he lived for 20 years.

Early in his time in Luxor, in 1862, Smith bought a beautifully preserved papyrus manuscript, covered in red and black ink. He knew enough to determine it was a medical document. But when he showed it to more experienced scholars, they didn’t recognize it as anything special. In their own notes, as Breasted wrote later, they “gave no hint of its extraordinary character and importance…. Thereupon it seems to have been totally forgotten by the scientific world.”

Breasted first saw the papyrus, which he called “magnificent,” when the New York Historical Society, having inherited it from Smith’s daughter, asked him to translate it. Only after he began his work did he recognize that one side of the papyrus was filled with some of the oldest medical records ever discovered. The papyrus itself dated back more than 3,500 years, but the surgical case studies were even older—already, when this copy was made, they had been handed down for a thousand years.

Compared to the case studies, which were unique in their age and their scientific rigor, the texts on the verso side of the manuscript, the “incantations and recipes,” as Breasted called them, were nothing special. These, he wrote, were “a magical hodgepodge” of instructions for guarding against pests or treating “female troubles.” They were added at a later date and, to Breasted, seemed to reflect the preferences of the papyrus’ owner, rather than important medical knowledge passed down through the centuries.

But Breasted wasn’t necessarily right to dismiss them. Even if they weren’t of the same value as the older case studies, recipes for face creams or female troubles were more closely aligned with the medical beliefs of the age than they are now. “They involved the same specialized knowledge of ingredients, amounts, and dosages as medicinal recipes,” says Allen, the Egyptologist, who teaches at Brown University. “As far as we know, dermatology was not a separate branch of medicine, or specialty, in ancient Egypt. Physicians who knew how to concoct a remedy for stomach aches could also come up with one for skin disorders.”

To Jacobs, the recipe for transforming a man to a youth did seem to involve some serious science. The key ingredient, hemayet, is subjected to a complicated series of manual and chemical procedures—husked, winnowed, sifted, boiled in water, dried, washed, ground, and boiled again. As much as a recipe, it looked like a set of chemistry instructions.

The first translation of hemayet he found, though, identified it as fenugreek, which didn’t make sense to Jacobs. Fenugreek is a wispy plant, its seeds easily harvested: it wouldn’t have needed to be winnowed and boiled so aggressively. But no one seemed to know what else it might be. Jacobs started calling Egyptologist after Egyptologist, asking if they knew what this word might mean, and no one did. Finally, about eight years after he first became curious about the recipe, someone directed him to Allen, who in 2005 had published a new translation of the papyrus.

Allen had an answer, based on the work of an earlier scholar, more experienced than the one who had guessed fenugreek. Hemayet was bitter almonds.

It made sense. Unlike fenugreek, almonds would need to be winnowed and husked, crushed and boiled, for any sort of face paste to be made. And there was another instruction that resonated with bitter almonds, too: the recipe said the boiled and dried hemayet fruits should be washed thoroughly in the river, until the water in the jar had “no bitterness at all therein.”

But there was another stumbling block, as Jacobs learned when he tried to procure bitter almonds to test. In the United States, they were illegal.

Bitter almonds are smaller, darker, and flatter than the sweet almonds that grow in California, the ones you’re supposed to eat as a healthy snack. Bitter almonds can also kill a person, quite easily. They contain hydrogen cyanide, and eating just seven or so nuts can be lethal.

Jacobs had to order the nuts from China, under a special research permit. “It was creepy,” he says. “I obviously didn’t want anybody to know I had them.” He sent a few to the chemist he had begun working with to understand the papyrus’ formula, and the rest he kept in his cupboard at home.

But once Jacobs and his colleagues processed the nuts, just as the papyrus instructed, they found that all that washing leached the poisonous compounds from the almonds. The bitterness leaving, Jacobs says, meant the poison was gone, too.

After the transformation, one of the compounds produced from the nuts was mandalic acid. For a dermatologist, this compound, a known extract of bitter almonds, would already have been familiar—starting just a few years before Jacobs got interested in the papyrus, dermatologists had started testing it as a treatment for acne and other skin problems. For Jacobs, it was a revelation: since first discovering the secret of hemayet, he has developed a patented formula for mandalic acid-based skin care products and written about his quest in a forthcoming book, Nefertiti’s Secret.

This story, in the end, is one more warning against dismissing knowledge that was not considered “scientific” by the scholarly (and stuffy) men of the 20th century. Even in their less surgical treatments, the Egyptians were sophisticated: millennia before our modern dermatologists, they had discovered a chemical compound that can make skin tighter and more elastic—in other words, that can transform the skin of an old man into the skin of a younger one.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook